The Life of John Thomas Mullock 4

Education

In his Pastoral Letter of February 22, 1857, Mullock expressed his vision for Newfoundland while encouraging the faithful to make themselves ready for their new role on the world stage: “A new era is now dawning on the country; wealth, commerce and population are increasing. No longer isolated, Steam and Electricity will render Newfoundland the connecting link between two hemispheres, placed by the Almighty in front of the New, and in close proximity to the Old World, surrounded by an ocean richer than all the mines of America or Australia, the future home of a great and noble people; it is absolutely necessary that the Catholic youth should have an education to fit them for the great destiny before them …”

Education was the most frequent and prominent theme of Mullock’s pastoral letters. “Considered in itself,” he wrote, “[e]ducation is the most important of all subjects in a social, a national, and a religious point of view” (February 22, 1857).

The year 1850 marked the beginning of the denominational school system in Newfoundland: the churches, receiving equitable amounts of government support, devised the curricula and ran the schools for the children of their respective parishes. In his pastoral letters, the bishop consistently praised the arrangement and the availability of education, writing on February 26, 1865, “Education without religion is a curse, not a blessing … Here all classes are agreed on this important subject, and the Government acts impartially towards all denominations.”

In many of his efforts to foster education, Mullock was following in the footsteps of Fleming, who in 1833 had founded in St. John’s a school for poor girls administered by the Irish sisters of the Presentation Order of the Blessed Mary, and in 1842 had founded Mercy Convent, which taught middle-class girls. Mullock strongly supported both these institutions and the religious communities that sustained them. Toward the end of 1849, on his first visit back to Ireland since becoming coadjutor, Mullock took the opportunity to deliver an “eloquent and impressive” appeal on behalf of the Presentation schools, which raised £70.[i] The following year, he similarly encouraged the people of St. John’s to support the “industrial, intellectual, and religious improvement of the children of [their] neighbours” through donations to the Presentation schools and convent.

Throughout his life, Mullock was particularly outspoken on the need for education for girls: “The greatest blessing that can be conferred on any community is the virtuous education of female children,” he wrote during his first year as bishop. “This is the foundation of the temporal prosperity and eternal salvation of future generations” (Pastoral Letter, December 15, 1850). A decade later, in a Pastoral Letter of February 27, 1860, he observed that “the spread of convent schools over the Diocese is most gratifying to every friend of Religion; to all who have the real interest of the rising generation at heart.” At a time when a small percentage of Newfoundland children (only 10.2 percent of Catholics and 13.3 percent of Protestants in 1861) enjoyed even rudimentary schooling, by the early 1860s these co-educational convent schools, which had better attendance rates and offered a wider breadth of curriculum, provided, in the words of one school inspector, “a very superior education.”[ii] By 1866, Mullock had extended the network of convent schools to thirteen parishes.

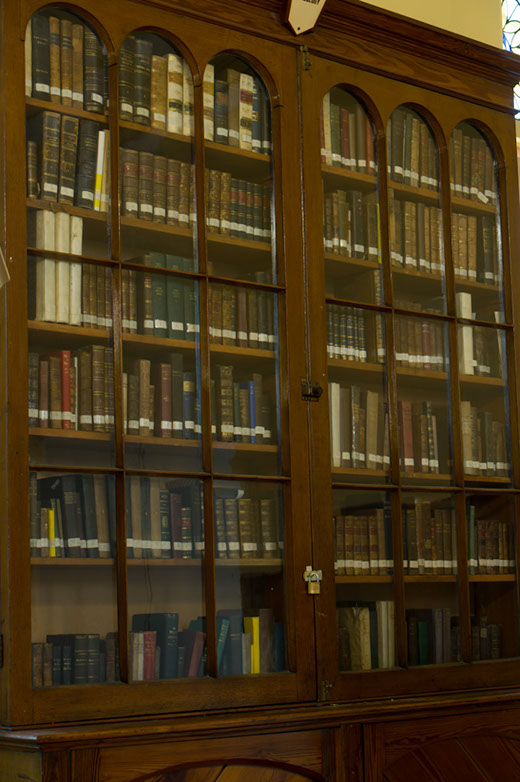

While Mullock and Fleming saw eye to eye on many aspects of education, Mullock differed from his predecessor on the need for a local seminary. While Fleming, fearing clashes between foreign- and native-born priests, had always opposed the establishment of such an institution, Mullock saw the fostering of a native priesthood as a priority. As early as 1850, he began collecting the Migne volumes that would form the core of the seminary library. Returning via Ireland from Rome and an audience with the pope in 1851, Mullock was reported by the Irish press to have immediate plans to establish “an extensive seminary” in St. John’s to serve the needs of the “widely extending diocese.”[iii]

Many of Mullock’s fellow bishops around the globe were of the same mind about the need for local seminaries. In the spring of 1852, Mullock sent his hearty congratulations to his friend, the Right Reverend Colin MacKinnon, bishop of Arichat, Nova Scotia, on the founding of his seminary (the present-day St. Francis Xavier University). Mullock also shared his own plans with Archbishop Hughes of New York, who added his encouragement. It was not until pastoral letter of February 19, 1855, that Mullock announced to his diocese his plans for “a Seminary for the education of Candidates for the Clergy.” Within a year or two, however, the plans for the educational establishment had extended to a seminary and a college equipped to educate boys “for any profession they may adopt” (Pastoral Letter, February 27, 1860).

On April 27, 1857, Mullock laid the cornerstone of St. Bonaventure’s College, named after his own alma mater in Spain. The college opened on October 4, 1858, and within a year had 70 day students, 28 boarders, and a full staff. For president of the college, Mullock chose a fellow Franciscan he knew from St. Isidore’s, Enrico Carfagnini (later bishop of Harbour Grace), who taught theology and philosophy. The curriculum, devised to rival that of any such educational institution in Europe, included “Christian Doctrine, Church history, English composition, grammar and spelling …; English history, geography; Latin, Greek, French and Spanish; algebra, geometry, arithmetic, mensuration, navigation, astronomy and bookkeeping, [as well as] singing and instrumental music.”[iv] Mullock was aided in his search for professors by John Henry Newman, rector of the Catholic University of Ireland (Entries #20, 21).

For Mullock, education was linked very closely to citizenship, another term that arises frequently in his pastoral letters. Several times he went as far as proposing that the right to vote be restricted to those with a basic education, while “not disenfranchising those now in possession” (February 23, 1868). As the years passed, Mullock’s exhortations to parishioners to educate their children in order to ensure their future political power and the very “survival of the country” grew more strident: “Knowledge is power;” he wrote on February 10, 1861,“and if the rising Catholic youth be left without the means of a refined education, they must sink in their own land, and strangers will come from the East and the West, and the native Catholics will be . . . excluded in great measure from the learned professions, from every high and honorable position.” Interestingly, when pressed for an opinion in 1865 on whether Newfoundland would join the confederation of the British North American Provinces (Entry #41), Mullock responded in letter stating that, in this likely future occurrence, the St. Bonaventure pupils would “perfectly qualified” for “the highest offices of the law and the government” or any such distinguished post in the Confederation.

Newfoundland Print Culture

Mullock continued his writing and publishing during his time in Newfoundland. In addition to his pastoral letters, letters on political and economic concerns, and other works already mentioned, he also published several lectures, the best known of which is his Two Lectures on Newfoundland, published in St. John’s and New York in 1860. These lectures capture the extent of Mullock’s explorations into Newfoundland history and geography and reveal his vision for the “great and noble country.” They reveal too Mullock’s belief in progress and the desirability of making connections. Outlining some of the historical circumstances that hindered Newfoundland’s growth from the time of European settlement, for example, Mullock writes, “Despite of all this [Newfoundlanders] have increased twenty-fold in ninety years, have built towns and villages, erected magnificent buildings, as the cathedral in St. John’s, introduced telegraphs, steam, postal, and road communications, newspapers, everything, in fact, found in most civilized countries” (22). As this passage suggests, Mullock believed that the printed word and global communication had a large part to play in advancing society. The book collection he offered Newfoundland, largely transported from Europe but also containing volumes from the United States and other British colonies, must have been in his eyes another mark of a sophisticated civilization.

Death and Tributes

At the age of 62, Mullock, who is thought to have suffered from diabetes and heart trouble, had been in ill health for many years. On the morning of Easter Monday, March 29, 1869, he collapsed on Garrison Hill and died a short time later at the Episcopal Palace.

Mullock bequeathed “all [his] lands, houses, pontifical ornaments, church vessels, vestments, church furniture, books and other chattels” to his successor bishop. He also stipulated that an amount of no more than £10 was to be spent on his burial. His body was waked Monday evening and all day Tuesday in the Episcopal Library, and then moved to the cathedral, where thousands continued to file through to pay their respects. Government, businesses, and banks closed on Thursday, the day of his funeral, and flags flew at half-mast.

The bishop’s death was noted with sorrow and respect in newspapers of all political and religious stripes. “Filius,” writing in the Chronicle, paid tribute to Mullock’s “extraordinary erudition” and “peculiarly gifted mind.” A long account of Mullock’s death and funeral was published in the Newfoundlander and reprinted in the Public Ledger. The Month’s Memory for the repose of the soul of Mullock was celebrated on Wednesday, April 30; on May 4, The Newfoundlander published the address given on the occasion by M.F. Howley, the future archbishop. Prefacing his words with a passage from Ecclesiastes on the “wise man”—“Nations shall declare his wisdom, and the Church shall shew forth his praise” (Eccl. 39:12–13)—Howley said of the late bishop, “No one could appreciate more highly everything that tended to enlightenment and progress. No one advocated more strongly than Dr. Mullock especially for this, his adopted country and people; his mind was ever at work, his voice ever uplifted to encourage intellectual and social advancement; he never disassociated this from religion itself.”

Mullock’s life was shaped by numerous religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions, and the spheres in which he made his mark were both local and transnational. Nowhere is the richness of his experience and evident than in his book collection, which embodies within four walls the many worlds of John T. Mullock.

[i]Limerick Reporter (December 4, 1949); “Public Thanks,” Limerick Reporter (December 14, 1849).

[ii]Phillip McCann, “Class, Gender and Religion in Newfoundland Education, 1836–1901,” Historical Studies in Education (1989): 179–200.

[iii]“Catholic Church,” Freeman’s Journal (May 29, 1851).

[iv]J. B. Darcy, Noble to Our View: The Saga of St. Bonaventure’s College (St. John’s: Creative, 2007), 18.