The Life of John Thomas Mullock 2

A Franciscan in Ireland

The Catholic Relief Act, also known as the Emancipation Act, of 1829, which brought the repeal of penal laws and a new dawn of public worship for Irish Catholics, also represented a renewed threat to the monastic orders. The new legislation required all regulars (under threat of banishment) to register, and prohibited both the training of novices and the return to Ireland of those educated elsewhere. Disconcerted, the Irish Franciscans contacted Daniel O’Connell, member of parliament and champion for Irish Catholic rights, who assured them in a letter of March 18, 1829, that the laws were “unexecutable.”

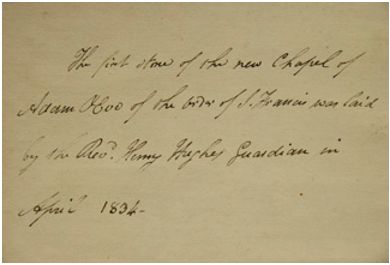

It was in this uncertain but hopeful new era that the newly ordained Mullock returned to Ireland. On the one hand, for several decades the Catholic Church had been engaged in a widespread program of building; on the other, the Franciscan order was weak. In 1830, only 33convents or friaries remained in Ireland, and more were closing every year as the friars died. After six months in his native Limerick, Mullock was posted to his first mission in Ennis, County Clare. Finding there a dilapidated friary, Mullock energetically set to work to strengthen the Franciscans’ presence and restore their way of life. To the consternation of the bishop, Mullock stopped ministering in the parish chapel and opened a new chapel, asserting the Franciscans’ right to a public church. Rome supported Mullock’s position.[i]

Ten years after Mullock’s death, his sister Mary de Pazzi wrote to a priest in Ireland that her brother’s “delight was particularly to build sacred edifices and beautify them,”[ii] and this delight in Re-building and growth characterized Mullock’s years in Ireland as well as those in Newfoundland. On October 28, 1832, Mullock was appointed as one of the fathers of Adam and Eve’s, the convent attached to the church of the same name (officially, the Church of St. Francis, now the Church of the Immaculate Conception) in Dublin, which was also undergoing renovations and expansion. In 1837, Mullock was elected guardian of the Convent of St. Francis in Cork, where he rebuilt the church in Broad Lane. In his diary for 1838, a satisfied Mullock recorded an account of the progress: 50 friaries were now active in Ireland, and eleven new churches had been established.[iii]

Mullock quickly distinguished himself as a capable administrator and inspiring leader. He advanced steadily within the order, holding his first appointment as definitor of his chapter in 1832. As provincial definitor, in 1837, Mullock attended a meeting of the Franciscan province in Dublin, at which he was appointed to see to a matter concerning the order in Rome. On November 1 of that year, Mullock returned from Rome to Dublin as the guardian of the convent of Adam and Eve’s. Over the next four years, he oversaw the total reconstruction of the Dublin church. In order to raise money for the project, in 1847 he went on a preaching tour of England and Ireland.

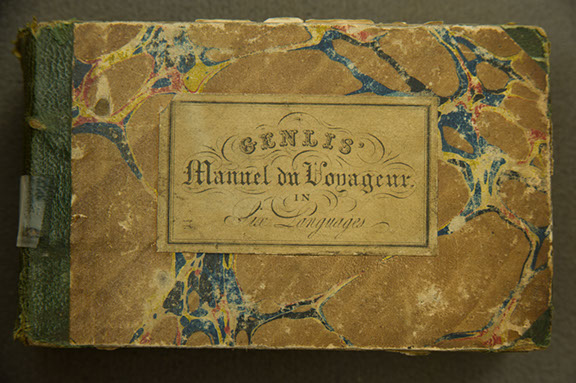

During these years, Mullock was also making his reputation as a scholar. The early to mid 1840s were a rich period for the Dublin book and periodical trade, and Mullock was actively involved in writing and publishing. His books, The Life of St. Alphonsus M. Liguori (1846) and his translation of Liguori’s The History of Heresies and Their Refutation; or, The Triumph of the Church (1847), appeared during this period, in addition to his translation “A History of the Irish Franciscans,” attributed to Father Hugh Ward, which was serialized in 1847.

The New World

Mullock had had ample opportunity to consider the New World. During his time in Dublin he served as an agent for the colonial bishops, and in 1847 alone had accompanied to Liverpool and Southampton two groups of nuns on their way to foreign missions. His good friend from Adam and Eve’s, Patrick Geoghegan (1800–1864), who later became bishop of Adelaide, had left Dublin for Australia in 1837, and other friends and acquaintances from his student days had been posted elsewhere in the British Empire and the United States.

In addition to the missionary movement, Ireland itself was experiencing a mass exodus due to the Great Famine (1845–49). On March 14, 1847, a little over a year before his own departure, Mullock wrote in his diary: “People going in thousands to America. The quay crowded as if a fair was going on with emigrants.” Due to starvation and disease on the one hand, and emigration on the other, the Irish population decreased from 8.4 million people in 1844, to 6.6 million in 1851. The emigration was a blow to Ireland but served to significantly strengthen Irish Catholic communities and sense of identity in North America.

As the historian Colin Barr has documented, the mid-nineteenth century was characterized by the rise of “Irish Episcopal Imperialism,” or, in the words of D. H. Akenson, “the spiritual empire of the Irish Catholic church.” This movement had one key player in the figure of the Irish-born priest Paul Cullen (1803–78), whom Mullock knew from his time in Rome. In his roles as the rector of St. Isidore’s from 1832 to 1850 and as Rome’s official agent for the colonial bishops from 1830, Cullen exercised immense authority in shaping the ethnic make-up (largely Irish) and ideology (ultramontane) that came to characterize English-speaking Catholic churches around the globe in this period.[iv] The decades between 1830 and 1850, when Cullen returned to Ireland where he would eventually become the archbishop of Dublin, were especially important for the “hibernicization” of the American Catholic church, a phenomenon bolstered by the waves of Irish emigrants to the United States.[v]

By September 1847, when he embarked once again to Rome, this time bearing a letter requesting his appointment as coadjutor bishop of Newfoundland, Mullock must have felt confident about his evolving role in this “spiritual empire.” Newfoundland may have particularly appealed to him. A British colony on the eastern edge of the North American continent, Newfoundland by this time had a well-established and large Irish population, and a history of Irish Franciscan bishops.

Mullock had first met Dr. Fleming, bishop of Newfoundland, in Dublin in 1833, and since that time Mullock had kept notes in his diary on the bishop and the colony. On June 30, 1846, Mullock recorded the news of the Great Fire: “Dreadful acc’ct of the total burning of St. John’s, Newfoundland. Dr. Fleming totally prostrated, as all he had in the world was burned.” When Fleming arrived in Dublin on June 5, 1847, he was, despite the significant setback of the previous year and his own deteriorating health, forging forward with the building of the St. John’s cathedral. He was also seeking to choose his successor, and Mullock, whom Fleming described in his letter to Rome as “learned, prudent, of the highest moral character, a distinguished preacher and endowed with all the qualities which should adorn a prelate of the Church,” was the person he wanted.[vi]

Mullock travelled quickly to Rome and delivered Fleming’s request. As the appointment process took several months, Mullock took the time to enjoy some sightseeing in Italy. North of Rome, he visited Capranica and Sutri (once governed by Pontius Pilate); he then headed east to Tivoli, and south to Naples, where he toured the Grotto of Posillipo (today the Crypta Neapolitana) and the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum In Rome he purchased the vestments and other ceremonial accoutrements he would need for his new role, along with a gift for Fleming (Entry #38).

Mullock was consecrated on the Feast of St. John the Evangelist (December 27, 1847) at St. Isidore’s. Cardinal Franzoni, prefect of the Propaganda, presided, assisted by two bishops, and a Swiss guard of honour was deployed. “Everything magnificent,” Mullock wrote in his diary.