The Life of John Thomas Mullock 3

Arrival in Newfoundland: Taking Stock

On May 6, 1848, Mullock arrived in St. John’s and, in a delicate move to ensure proper respect was paid to Fleming’s position and feelings, quietly disembarked in a small craft before the ship docked, in order to avoid the crowds who had gathered to meet him.

In his first year in Newfoundland, Mullock took stock of his new surroundings. Between June 23 and September 10, he undertook his first visitation of the south and west coasts of the island, covering hundreds of kilometres of coastline and travelling to places “[n]ever before visited by a N.F.L. priest.” (In a ten-week visitation in 1852, he circumnavigated the island and toured Labrador, visiting a total of 28 communities.) In his notebook, Mullock recorded the population statistics from the census of 1845: Total population: 95,506; Catholics: 46,995; Protestants (all denominations): 51,511; increase in the population of the island since 1836: 30 percent. Twelve years later, in his Two Lectures on Newfoundland, Mullock offered what he saw as a conservative estimate of Newfoundland’s population in 100 years’ time: 1.3 million people. In his eyes, Newfoundland was poised to become an important centre in North America, and from this moment he worked toward this future with optimism and vigour.

The growth of the colony enabled both Fleming and Mullock to gain and maintain greater autonomy within the church hierarchy. In 1847, the church in Newfoundland had been raised from a vicariate apostolic to a diocese, one attached to the ecclesiastical province of Quebec. (Mullock had in fact first heard this news in Rome on the day he learned of his appointment as coadjutor.) In October 1850, due to the efforts of Fleming, the diocese of Newfoundland was changed from a suffragan see of the Quebec archdiocese to a direct dependency of the Holy See. In 1851, Mullock in turn opposed the plan to attach the diocese to the newly formed ecclesiastical province of Halifax. Arguing distance, population, and the advanced development of Roman Catholic church in Newfoundland, he made his case to the pope on a trip to Rome. In 1856, Mullock secured the creation of a second diocese in Newfoundland: the Diocese of Harbour Grace. John Dalton (1821–69) was consecrated bishop of the new diocese, and Mullock’s title became bishop of St. John’s.

The rapid development of Newfoundland may have also helped Mullock regard Newfoundland his “adopted country” and home. Within five years of his arrival, Mullock had four members of his family in St. John’s: his beloved father, his sister Mary, his brother Thomas, and Thomas’s wife, Charlotte Frances. Each lent his or his talents to the life of the diocese: his father built furniture for the cathedral and Episcopal Library; Mary was professed Sister Mary Magdalen de Pazzi at the Presentation Convent in 1854 and served as its superior from 1875 to her death in 1889; and Tom became the cathedral organist as well as the first piano teacher at St. Bonaventure’s College.

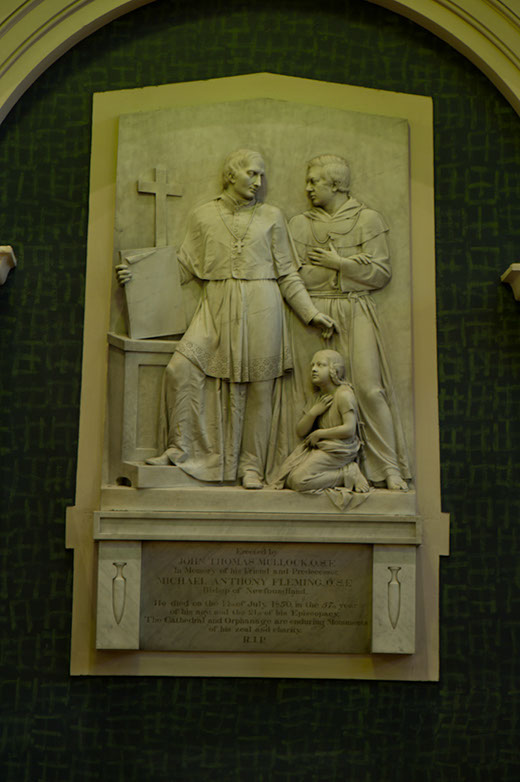

During Mullock’s first two years in St. John’s, he and Fleming were busy with the preparations for the cathedral. In separate trips, both men crossed the Atlantic in 1849 to commission some of the statuary that would adorn the edifice and its grounds, including John Hogan’s masterwork The Dead Christ (1854) and several statues by the Irish-born and London-dwelling John Carew (c.1782–1868). When Bishop Fleming died on July 14, 1850, Mullock memorialized his predecessor as the visionary behind the cathedral and as a benefactor of poor children with a marble bas-relief by John Hogan showing Fleming with one hand holding the plans for the construction and the other gesturing compassionately toward an orphan girl.

The Hogan bas-relief was one of many artworks Mullock bought or commissioned during trips to Europe through the 1850s. Along with Italian statuary and stained-glass windows of the firm of William Warrington of England, copies of famous paintings produced by the Paris workshop of Jacques-Paul Migne (also a major supplier of Mullock’s book collection) also adorned the cathedral interior in Mullock’s day. Mullock did not neglect the outdoor space: along with Carew’s statues of St. Patrick, St. Francis of Assisi, and the Immaculate Conception, Mullock also oversaw the installation of an impressive entrance arch topped by a marble statue of St. John the Baptist by the Italian Filippo Ghersi. In the mist of these plans, Mullock explained in his July 14, 1856, Pastoral Letter, that in the courtyard “the people of St. John’s will have a place of recreation such as few Cities can boast of, where Art and Religion will refine the minds of the young, and where all may breathe the pure air and enjoy the glorious prospect of land and sea”

Among the fine art works in the cathedral were two of great personal significance to the bishop. Mullock and his siblings donated the central stained-glass window in the apse (now largely obscured by the high altar installed in 1955) in honour of their parents. In the west transept, the bishop placed a marble monument to the memory of his father, who died on April 14, 1858, and was buried in the cathedral near the statue of St. Patrick. While Thomas Mullock, who had built many of the first pews in the cathedral, had requested to be buried in it, the impressive monument is one of numerous indications that Mullock deeply mourned his father and wanted to keep his memory alive (Entry #38). Produced by Ghersi in Rome, the monument arrived with a shipment of books in the spring of 1860 and was installed on the second anniversary of Thomas Mullock’s death.

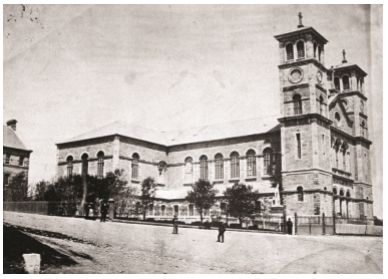

The cathedral was consecrated on September 9, 1855, by Archbishop Hughes of New York. The bishops of Toronto, New Brunswick, and Arichat (now Antigonish), along with 22 Newfoundland priests, were also present for the event, which comprised two weeks of lectures, services, and celebrations. To underscore the impression that the completion of the cathedral was not a concluding chapter but rather a prologue to continuing development, Mullock capped his visitors’ itinerary by laying the cornerstone for what would become the grand stone edifice of St. Patrick’s Church. Following these festivities, Mullock gathered the detailed report of the consecration printed in the Newfoundlander together with his own history and description of the cathedral, and published The Cathedral of St. John’s, Newfoundland, with an Account of its Consecration (Dublin: Duffy, 1856).

Envisioning Newfoundland: “The first link in the electric chain”

During his 21 years in Newfoundland, Mullock made at least seven trips back to Europe. He also travelled several times to New York, as well as to other American cities (Philadelphia, Baltimore), and toured Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and the Province of Canada. Mullock’s taste for travel and his openness to new sights and experiences are evident in his diaries, which record his itineraries and impressions in some detail. His enthusiasm for much of what he encounters is palpable, for example, when he reflects on December 27, 1851, “I saw during the year the greatest wonders of nature and art, Northern icebergs of the largest size, Niagara and the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes of America, The Exhibition at the Chrystal Palace in London, Paris, St. Peter’s, Rome and the Pope, etc.”

This mention of the “Great Exhibition” at the Chrystal Palace of 1851, which showcased innovations in manufacturing from around the world, points to Mullock’s embrace of technological advancements. In particular, Mullock was eager to have St. John’s benefit from modern advances in transportation and communication. In 1851, there was a coordinated movement in St. John’s to make the city a port of call for the steamers that were running between Europe and the United States. Mullock took considerable personal initiative in promoting steam connections to St. John’s. On April 25, 1851, having heard that Galway was poised to become a “packet station” for America, he wrote a letter, which was published in the Irish newspaper Freeman’s Journal (May 31, 1851), to Thomas R. Russ in Galway, presenting a strong case for St. John’s being the first port of call for the transatlantic steamer. Offering a calculation of how much less coal would be needed to be carried on board to reach St. John’s rather than Halifax, Nova Scotia, Mullock argued that a stopover in St. John’s would actually shorten the trip to the Boston by 24 hours.

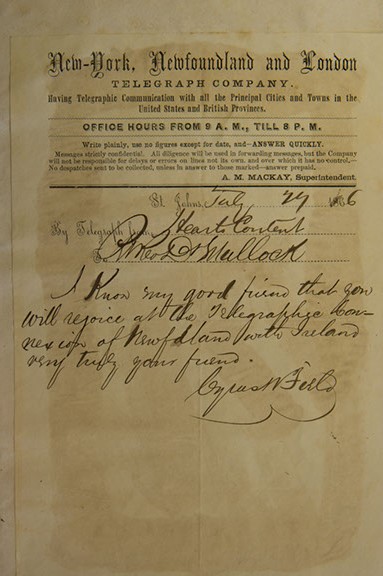

Steamships were not the only modern means of connection Mullock envisioned for Newfoundland. In his letter to Russ, Mullock made an interesting comment: “I saw six months ago, suggested in one of your journals here, the feasibility and necessity of making this [St. John’s] the general telegraph station for the whole continent—in fact the telegraph link between the New and the Old World.” Here it is very likely that Mullock is, in a rather wily manoeuvre, referring to his own letter, signed “J.T.M.,” which appeared in the Morning Courier on November 8, 1850, and is sometimes credited as the first mention of the transatlantic telegraph in print. In the letter, Mullock urged the architects behind the cable to make St. John’s, not Halifax, the American terminus. He concluded, “I hope the day is not far distant when St. John’s will be the first link in the electric chain which will unite the Old World with the New.” From the first attempt to lay the cable in 1858 to the final success in 1866, Mullock remained intensely interested in the realization of the transatlantic telegraph communication, and develop close relationships with two of the major backers of the project, Cyrus Field and Peter Cooper of the New York, Newfoundland & London Electric Telegraph Company (Entry #42).

Mullock played a strong role in Newfoundland public affairs from the 1850s to the early 1860s. He made his political debut on February 7, 1852, with a letter to Philip Francis Little (1824–97), a young barrister and member of the Liberal party. Responding to the Colonel Office’s hesitation to grant responsible government, Mullock’s letter was a scathing indictment of Britain’s and the Newfoundland House of Assembly’s mismanagement of the colony. The letter was printed and distributed widely as a broadside and marked the beginning of Mullock’s (and by extension the Catholic church’s) support for Little and his cause of responsible government. Although the letter prompted an immediate complaint that the clergy should not be involved in politics, Mullock countered this with a letter to the Pilot: “I cannot see why a priest is to be deprived of his right to citizenship more than anyone else.” Due in great part to Mullock’s support, Little became premier in 1855, and responsible government was achieved.

In unapologetically exerting his influence in these matters, Mullock maintained that the “spiritual and temporal interests” of his diocese were his purview as bishop (Pastoral Letter, February 10, 1861). Through the late 1850s, however, he quickly grew disillusioned with the Liberals’ handling of poor relief and funds for roads and steam communication. Frustrated by the lack of advancement on concerns that he thought were vital to the colony, in 1860 Mullock famously took matters into his own hands and personally arranged on a trip to New York for a steamship to connect St. John’s and the Newfoundland outports. Upon his return, the government rightly protested that Mullock had not been authorized to make such arrangement, causing the bishop to publish an angry letter “To the Catholic People of St. John’s” on June 4, 1860. Alluding to the persistent difficulties he himself faced on his visitations, Mullock wrote, “Will strangers believe that in a British colony, the shire town of Fortune Bay, two hundred miles by sea from St. John’s, is in reality farther from us than Constantinople; but then we have the satisfaction of seeing thousands and thousands of pounds distributed among our locust-like officials.” While steam service for the island and Labrador was soon inaugurated, Mullock’s frustration with the government’s decision-making was clear.

The episode reveals Mullock’s deepening divide with the Liberals and coincides with the period of political unrest that culminated in the violent events that took place in Cat’s Cove and St. John’s in 1861 (Entry #39). While commentators have argued that Mullock played a part in fueling sectarian discord,[i] in his own published letters and sermons his response to the violence was firmly on the side of law and order. In any case, the unhappy episode marked the end of Mullock’s active involvement in political questions. In his Pastoral Letter dated just one year later (March 2, 1862), Mullock wrote that he would not speak of the “sad events which disgraced this country” and expressed “confidence” that Newfoundland would once again be a model of “peace, order, mutual forbearance, and good feeling.” Avoiding a direct commentary on the situation, Mullock offered instead some unflinching common sense: “Those quarrels about what are called politics in this Country ought to have no existence.... They are in general but a disreputable struggle for place, not principle.… Catholics and Protestants in possession of the same rights have the same interests.”

Even Mullock’s critics concede that throughout his tenure the bishop appeared to be genuinely motivated by the interests of the people in his diocese. His notebooks and pastoral letters reflect his observations of the hardships people faced, such as the cholera outbreak of 1853, which resulted in 6,000 deaths, or the all-around dismal year of 1860, with “6 or 8 child burials a day from diphtheria and measles” in the summer, a potato blight, and a poor fishing season. Mullock endeavoured to be of service to all parts of his large diocese, as evidenced by, for example, his eighteen-year correspondence with Father Alexis Bélanger (1808–68), the isolated francophone priest stationed in Bay St. George on the west coast of the island.