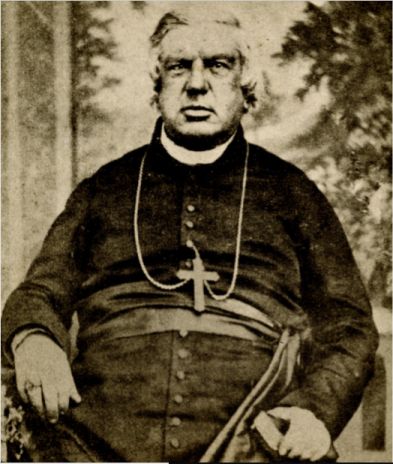

The Life of John Thomas Mullock

A profound and practical thinker, John Thomas Mullock (1807–69) was a man of exceptional ability, strong allegiances, and far-reaching vision. The successor of Michael Anthony Fleming as Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland, the Right Rev. Dr. Mullock arrived in St. John’s in the spring of 1848. Over the next 21 years, he made many contributions to the growing colony. He completed and ornamented the cathedral (since 1955, the Basilica of St. John the Baptist) begun by Fleming, as well as establishing an orphanage, a college, and numerous churches, convents, and schools. He advocated for better roads, for steamship communication, and for the as-yet-unimagined Atlantic telegraph cable. He capably exerted his influence on governing bodies from the nascent Catholic Board of Education to the Newfoundland government, and worked effectively within the church hierarchy. As an author and translator, he enriched European and North American readerships with his scholarship on religious and secular subjects.

Among his many legacies, Mullock’s library stands as testament to his life and learning. As various and rich as the interests of man itself, this personal collection was donated by the bishop as the library for St. Bonaventure’s College (est. 1857) and was intended, by him, for use as a public library. Through this collection, we can trace the life of man who was both a citizen of the world and a tireless proponent of his adopted home.

Early Life, Education, and Ordination: Ireland, Spain, and Italy

John Thomas Mullock was born on September 27, 1807, in Limerick, Ireland, to Thomas Mullock (1781–1858), a woodcarver and furniture maker, and Mary Teresa Hare (d. 1841). The Mullocks appear to have been nurturing and pious parents, who encouraged a love of religion, learning, and music in their children. The eldest of thirteen[i] and a gifted student, John Thomas spent his childhood and early adolescence in Limerick, studying classics at a local academy and taking private lessons in French.

Mullock’s youth coincided with the last years of the penal laws, legislation that had been passed against Roman Catholics in Britain and Ireland in the 1690s. In addition to curtailing Catholics’ civil rights (Mullock’s own ancestors were said to have lost possession of their land), the laws placed strictures on Catholic public worship as well as the training and ordination of priests. Although the penal laws affecting the clergy had been greatly relaxed through the eighteenth century, their effect on the religious orders, such as the Franciscans, had been significant. These orders had survived due in a large part to the network of Irish colleges that had been established across continental Europe over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries following the Reformation. When Mullock displayed signs of a religious vocation, therefore, his spiritual advisor, a Franciscan father, proposed finding him a place at a college in Rome. It is possible that Mullock’s father at first was reluctant to send his young son away; for whatever reason, Mullock did not go to Rome. Instead, on June 13, 1823, at the age of sixteen, he boarded a Portuguese ship destined for Spain.

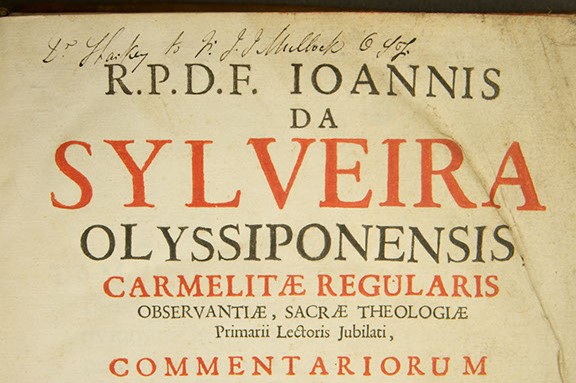

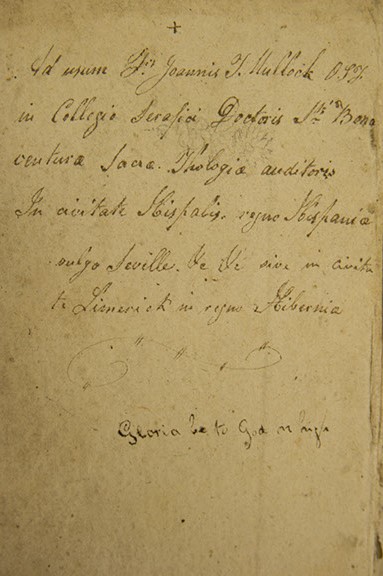

In Spain Mullock joined a Franciscan convent near Seville to study philosophy and theology. In his Ecclesiastical History of Newfoundland, Volume Two, M. F. Howley (1843–1914) identifies this convent as El Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Loreto del Partido de San Lucar La Major; other evidence, including his book collection, indicates that Mullock completed his studies at the College of St. Bonaventure.[ii] On December 7, 1825, Mullock received the habit of the order of St. Francis. From there, according to Howley, he spent a year as a novice at the convent of Xeres in the province of Cadiz and was professed—made his primary or simple vows—on December 21, 1826. For the next two years, Mullock continued his studies in philosophy and theology, becoming a sub-deacon in 1828.

Mullock’s six years in Spain were happy and fruitful ones. Soon fluent in the language, he became a lifelong admirer of the Spanish people, culture, and literature. His book collection today retains numerous volumes from his student days, including student editions of the New Testament and a Greek-Latin lexicon, as well over a dozen volumes of Spanish religious and literary works. Inscriptions in the books suggest that the network of Irish colleges in Spain sustained a closely knit community of scholars.

Years later, during his bishopric in Newfoundland, Mullock demonstrated his continued appreciation for the Spanish. In 1860, a report of boys throwing rocks at Spanish sailors provoked an angry admonition from the bishop on the youths’ “ingratitude”: “In the dark days of Ireland’s sorrow,” he wrote in a letter published in a local newspaper, “Catholic Spain was the refuge, the home of the persecuted Irish. The Spanish Colleges and Convents were open to every Irish student, and to the liberality of Spain, Ireland owes in a great measure the preservation of her Church and, consequently, Newfoundlanders, their religion. I myself should be the most ungrateful of men, if I could forget that noble people among whom a portion of my youth was spent, and my ecclesiastical studies prosecuted.”[iii]

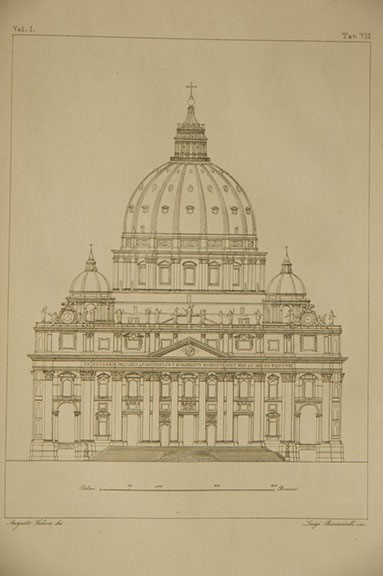

In June 1829, Mullock left Seville for the Irish Franciscan College of St. Isidore’s in Rome, where he competed his studies in theology. Founded in 1622, St. Isidore’s was—and remains today—a premier institution of the Franciscan order. It was one of the minority of colleges to have had a more or less uninterrupted existence through the Napoleonic period, and it played an important role in the global Catholic Church through the nineteenth century. With its venerable library and vibrant community, St. Isidore’s was undoubtedly inspiring for Mullock, who perfected his Italian and French as he worked toward his ordination.

The art and architecture of Rome also profoundly impressed the young novice. It was during these years that Mullock first met the Irish artist John Hogan (1800–1858), at whose studio he and other Irish students were frequent visitors. Mullock was also awed by the architectural heritage of Rome, from the classical antiquities to the Vatican. As he recalled in a 1860 lecture, “The dreams of my boyhood were realized by the sight of the imperishable monuments of ancient pagan Rome, and by the glorious edifices and institutions of the Christian Capital of the World.” Particularly moving were the catacombs used by the early Christians: “How many hours have I spent in my youthful days in the Catacomb of St. Sebastian, musing among the hollow niches, and the sepulchres of the martyrs, or in the humble recess which served as a Cathedral, and comparing that with the dome of St Peter’s and the splendours of the Vatican! I merely speak of the impressions these scenes made upon my own mind.… [O]n me they always had the effect of exciting the most lively emotions of faith, and a most ardent desire … of labouring until death for the glory of the Church whose humble child I was.”[iv]

By canonical dispensation, Mullock was ordained by Cardinal Giacinto Placido Zurla at the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran in Rome on April 10, 1830. He was 22 years old. Mullock was now prepared to return to Ireland as a priest, but on his return he served a brief stint as a chaplain in the Royal Forces in France. The Franciscans, called “King’s priests,” had traditionally served in such positions since the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715). According to Howley, Mullock was in Paris to witness the July Revolution (July 27–29) that led to the abdication of Charles X.