Royal Navy in the Early 18th Century

To study the legal history of early Newfoundland is in large measure to chronicle the presence of the Royal Navy. The navy was the engine of law and authority in Newfoundland. Its administrative infrastructure formed the mainstay around which the island's district system was built. English historians have thoroughly discredited the traditional view of the Georgian navy as corrupt and inefficient, and its position in Newfoundland requires a complete reappraisal. Far from conforming to the popular stereotype of quarter-deck despotism, 18th century naval administration effectively managed the largest industrial organization in the western world. The commodores of the annual squadron sent to Newfoundland proved willing and able to administer law and government at St. John's.

Despite the limited institutions allowed under King William's Act, at the local level events transcended statute and official policy. A series of ad hoc arrangements began to address the island's basic needs in the early 18th century, establishing the precedents for the legal system which later became entrenched as naval officers extended their judicial role beyond their appellate jurisdiction. The most important aspect of this process was the judicial function of the Royal Navy, whose officers extended their role well beyond the appellate jurisdiction authorized by statute law. The naval commodore and his officers represented the only force capable of consistently enforcing English authority throughout the outports.

The first formal legal records were created by Captain Josias Crowe. As the naval commodore and commander-in-chief, Captain Crowe convened the island's first type of informal legislative assembly in 1711. From August to late October he presided over a series of public meetings attended by masters of fishing ships, merchants and prominent townspeople, which approved several by-laws for keeping the peace and settling disputes. Known popularly as "Captain Crowe's Law," the sixteen provisions contained both general regulations and specific warrants. In addition to rulings on property disputes and orders for maintaining coastal defenses, the articles stipulated that servants who hired themselves out to more than one master were to be fined two pounds or whipped three times in public.

Captain Crowe also established penalties for offences. He forbade the selling of liquor on Sunday, upon a fine or forfeiture of 40 shillings for the first offense, eight pounds for the second, with a fine of one shilling for each person found in a disorderly house. Other measures went unrecorded: in his report to the British government, Crowe simply stated that he had suppressed debauchery by unspecified threats, punishments, and other necessary measures. Though Crowe had not acted according to any known instructions, his initiatives established an early precedent for the customary legal system in which the naval commodore consulted with merchants and townspeople, and took steps to meet the perceived needs for law and order. Naval officers held courts that eventually became an integrated part of the island's judiciary.

When Sir Nicholas Trevanion, captain of HMS York, arrived in 1712, he operated this customary system as if it had dated from time immemorial. Like his predecessor, Trevanion convened an ad hoc legislature in St. John's–attended by the fishing admirals, merchants, and other prominent inhabitants–which debated and adopted six by-laws. He reported that he held a general court twice a week, assisted by the fishing admirals. To account for its operation, Trevanion asserted that the court simply tried to settle outstanding disputes by using the most practical available means. During his stay he received complaints about neither the conduct of the fishing admirals nor the implementation of King William's Act. To enforce Sunday observances, he posted orders, appointed a watch, and punished offenders. Trevanion claimed that when he sailed back to England, he left St. John's in a good condition, with the townspeople well satisfied with the state of law and order. Such a sanguine voice was rarely heard from Newfoundland. Over the next decade the Board of Trade received a steady barrage of petitions on the need for civil government, regular courts, and winter magistrates.

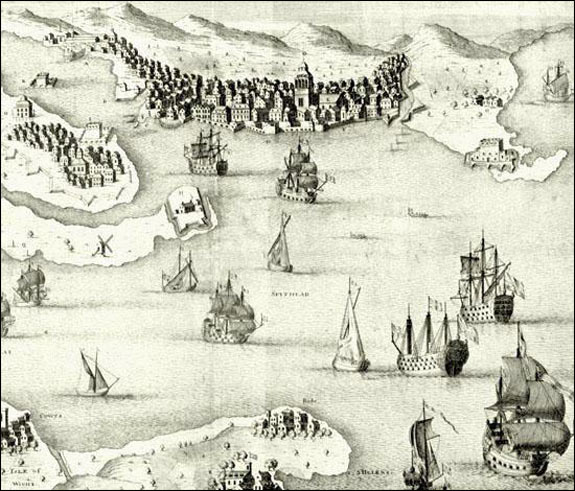

At the heart of these complaints were two basic constraints on the pre-1729 naval system. First, the judicial arm of the Royal Navy in Newfoundland did not reach much further than St. John's harbour. Communities in the more remote bays rarely received calls from the squadron's busy frigates which, in any case, were unsuited to navigating narrow coves and shallow harbours.

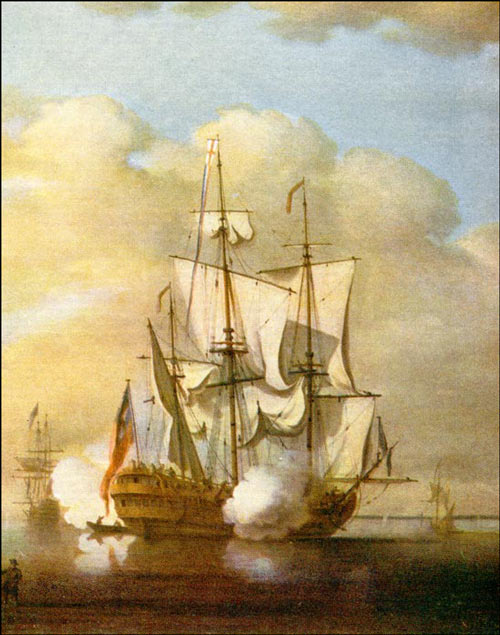

The squadron sent to Newfoundland usually consisted of at least two rated warships and an armed sloop. The flagship was typically a fourth- or fifth- rated warship of 40-60 guns, with two decks, a complement of 220-400 men, and a displacement of 650-1,000 tons. Commodores on the Newfoundland station often commanded a 50-gun flagship (such as the Litchfield, Sutherland, Romney, Guernsey, Antelope, and Salisbury), though 40-, 44-, and 60-gun warships were also used on occasion. The flagship of Commodore Rodney, for example, was HMS Rainbow, a 40-gun, fifth-rate ship, with 240 men. Sloops were unrated warships, with 8-18 guns, 80-130 men, and 140-380 tons. By contrast, the schooners and brigs used in the Newfoundland fishery were commonly two-masted vessels of 30-80 tons. Not until the second half of the 18th century did commodores arrange for their junior officers to command schooners, to cruise specific districts along the coast, and to convene surrogate courts.

Second, regardless of the commodores' efforts, the squadron rarely stayed in Newfoundland for more than ten weeks each year. The length of the visit depended upon a range of factors–from Admiralty politics to the ships' state of repair–but the warships usually arrived off Newfoundland in July or August and returned to England, often via Lisbon, by the end of October. Two factors fixed the time of departure: the duty to escort the British fishing fleet and the need to avoid the onset of weather conditions that made the Atlantic crossing excessively hazardous. From the viewpoint of judicial administration, this meant that the island relied upon the fishing admirals for the remainder of the spring and summer. Fishing ships typically began to arrive in early May, after which the fishing admirals were appointed. No competent legal authority therefore existed on the island from November to April, and this problem was not addressed until the appointment of the island's first justices of the peace in 1729.

In spite of these difficulties, the role of the Royal Navy in the island's judicial administration continued to grow throughout the 18th century. Each year the commodore presided over a series of official ceremonies that marked the familiar rhythm of public life. These customs became integral parts of the legal culture that persisted well into the 19th century. Historians have typically viewed the presence of the Royal Navy in port through the lens of maritime culture, particularly the impact of sailors on popular politics, patterns of crime, and other social problems. But with hundreds of men and thousands of pounds invested in the defense and government of Newfoundland, the Admiralty demanded that its squadron be well disciplined, for the warships comprised both the symbolic and material power of the British crown.