The Peckford Government 1979-1989

The aggressive pursuit of resource management dominated A. Brian Peckford's time in office. Offshore oil, the fisheries, and hydroelectric developments topped the agenda. In all three areas, Peckford hoped to wrestle control from outside interests to secure greater revenues for the province. Resource management, he argued, would end Newfoundland and Labrador's status as poorest province and restore pride of place to the people.

Although Peckford made significant gains in the oil industry, the prosperity he hoped for did not materialize during his premiership. Disputes with Ottawa, legal battles, and a weak international market hindered progress. By the time he left office in 1989, the province remained the most debt-burdened in the country, with high unemployment and low personal income. Still, the Peckford administration laid the groundwork for future oil developments, which, in 2008, fulfilled his famous prediction that "Some day the sun will shine, and 'have not' will be no more."

A New Political Outlook

Peckford's work as Minister of Energy and Mines from 1976-79 paved the way for his premiership. Bold and tenacious, he fought hard for provincial control over an emerging offshore oil industry. In 1977, Peckford released a comprehensive set of exploratory drilling regulations aimed at ensuring that the industry would primarily benefit the province. Oil companies halted drilling in protest, but then complied in 1978.

Peckford's aggressive style placed him in frequent conflict with multinationals and the federal government, but made him popular with voters and the provincial Progressive Conservative Party. After Frank Moores announced his resignation in January 1979, Peckford won a leadership convention in March and a general election in June.

The change ushered in a new style of provincial politics. Peckford, 36, became the youngest first minister in Newfoundland's history and one of the few members of the political elite from a working-class outport background. Peckford worked as a teacher before entering politics, where his assertive and often combative approach contrasted with Moores' laid-back manner and Smallwood's deference towards Ottawa.

Disillusioned with what he called the "false prosperity of the first three decades of Confederation" and the province's continued dependence on federal transfer payments, Peckford strove for greater political independence from Ottawa through constitutional reform. He rejected Smallwood's policies of centralization and industrialization and felt the fishery deserved more attention. Peckford supported rural development and economic growth through the sound local management of the fishery, oil and other natural resources.

Peckford's goals and confident rhetoric resonated with an emerging mood of nationalism in Newfoundland and Labrador. What has been called a "cultural renaissance" celebrated the province's distinctive traditions and heritage, and a new generation of voters rejected the widespread assumption that Newfoundland was in some way inferior to the other provinces. They supported Peckford's promise to build a prosperous, proud, and more independent Newfoundland and Labrador based on provincial management of natural resources.

Resource Ownership

A stumbling block in Peckford's plan was that outside interests already controlled much of the province's natural resource sector. The fisheries had been under federal control since 1949, and the disastrous Churchill Falls agreement benefited Quebec far more than Newfoundland and Labrador. Corporate interests dominated other industries, for example the Iron Ore Company of Canada in Labrador West, and Abitibi-Price, Bowaters, and Kruger Inc. in forestry. Offshore oil was a new and lucrative industry, but the federal government challenged the province's claim to ownership.

Churchill Falls was a particularly galling reminder of lost revenues and political powerlessness. Under the 1969 contract, Newfoundland and Labrador agreed to sell cheap electricity to Hydro-Quebec until the year 2041. The 65-year contract made no allowances for inflation or revision. The Peckford government failed repeatedly to renegotiate a better deal with Quebec and could not persuade Ottawa to intervene.

Protracted legal battles consumed time and resources, and ended in failure. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled twice in Quebec's favour, in 1984 and 1988. The province sought to develop power on the Lower Churchill River, but could not secure a transmission route through Quebec into lucrative American and Canadian markets. Thus it remained undeveloped.

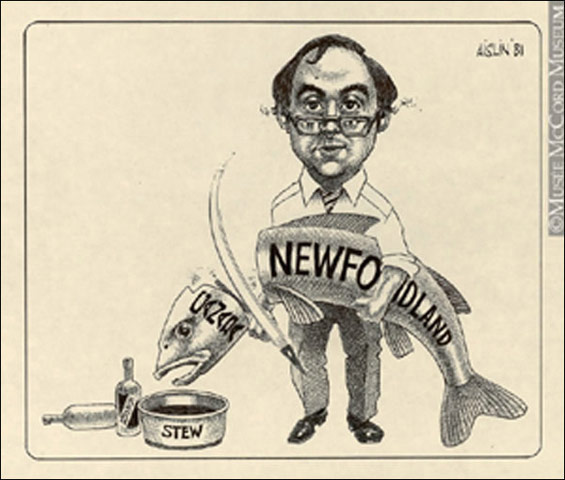

Although the fisheries were the economic mainstay of rural Newfoundland and Labrador, they fell under federal jurisdiction. Ottawa determined fish quotas, distributed trawler licenses, and set all other aspects of fisheries policy. Peckford tried to acquire greater provincial control of the fisheries under the 1982 Canada Act, but could not get enough support from the other premiers. Unable to reclaim fisheries jurisdiction through constitutional change, the Peckford government did its best to influence federal fisheries policy in the political arena.

Peckford argued the province had a historic and moral right to the fisheries and should therefore have a say in their management. He demanded that Ottawa reserve the bulk of all cod stocks for the province's mid-shore and inshore fishers, leaving any surplus for larger offshore trawlers. When the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans issued licenses to three factory freezer trawlers in 1985, Peckford declared it a "disaster of monumental proportions." Overfishing remained a problem for the rest of the decade and the stocks collapsed in 1992.

The province, however, also contributed to overcapacity. It allowed too many fish plants to operate and supported Ottawa's efforts to equip inshore and mid-shore fishers with larger boats and more sophisticated technology.

Offshore Oil

Unlike other natural resources, offshore oil provided an opportunity for the Peckford administration to gain control over a lucrative new industry. Although the Supreme Court of Canada decided in 1984 that the resource fell under federal jurisdiction, Peckford negotiated a deal with the Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney giving the province equal say over offshore management and a large slice of all revenues.

This was the 1985 Atlantic Accord, which also protected equalization payments for a 12-year period. Otherwise, income from oil royalties would have been set against equalization transfers, which would have been reduced. Peckford successfully argued that because oil is non-renewable and can therefore provide only short-term revenues without reflecting the province's true fiscal capacity, it should be treated differently from renewable resources in the equalization formula. The Accord received widespread support and was hailed as a turning point in the province's economy. However, oil prices dropped, and production was slow to get underway. The first oil did not flow from the Hibernia field until 1997, almost a decade after Peckford left office.

Other Developments

Although resource development dominated the political agenda, the Peckford administration dealt with other issues as well. A new provincial flag was adopted in 1980, Grade 12 was introduced in 1983, and construction began on the Trans-Labrador Highway the same year. The first women were appointed to the provincial cabinet in 1979 - Lynn Verge and Hazel Newhook - and Margaret Cameron became Newfoundland's first woman Supreme Court justice in 1983.

Constitutional reform also marked the Peckford years. In 1981, he was instrumental in adding a clause to the Canadian constitution recognizing affirmative action programs. He was a signatory to the 1987 Meech Lake Accord, which he hoped would decentralize federal authority and give the province a greater say over fisheries and offshore oil management. The government later retracted its support under Liberal Premier Clyde Wells.

The late 1980s brought economic hard times to Newfoundland and Labrador. A global recession damaged the province's resource-based economy and the fish stocks dwindled to dangerously low levels. Peckford's promises of rural development had given way to make-work projects and federally administered employment insurance programs. Unemployment exceeded the national average and the provincial debt was the highest in Canada.

In 1987, the Peckford government backed Alberta promoter Philip Sprung's plans to build hydroponic greenhouses on the island and sell cucumbers in Atlantic Canada and the eastern United States. The cucumbers, however, could not compete with cheaper produce on grocery store shelves and at times sold for half the cost of production. The province poured $22 million into the project, which ended in economic failure.

The Sprung controversy and continued economic hardships damaged Peckford's popularity. His frequent conflicts with Ottawa also took a toll. On 21 January 1989, Peckford announced his retirement and was replaced by the fisheries minister, Tom Rideout, at a March leadership convention. A general election the following month elected a Liberal majority to the House of Assembly, under the leadership of Premier Clyde Wells.