Origins of Migratory Fishery

The 16th century was a time of exploration and expansion for Western Europe. Many nations, including France, Portugal, Spain, and England, extended trade routes beyond their borders into Africa, Asia, and the New World, where they hoped to profit from newly available goods: tea, silk, and spices from Asia; gold and ivory from Africa; tobacco, furs, and other animal resources from the Americas.

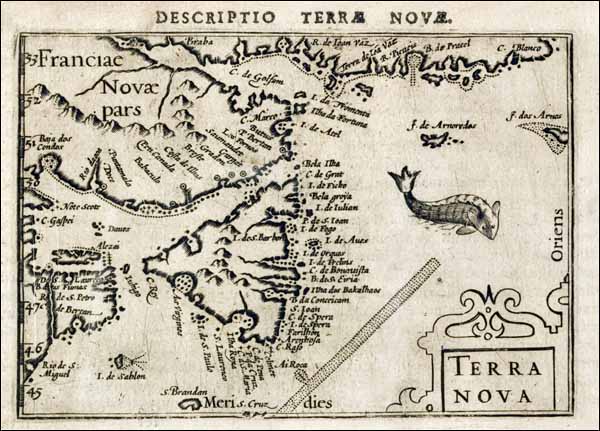

Abundant cod stocks off Newfoundland and Labrador's coasts earned the attention of several European nations. Within a decade of John Cabot's 1497 voyage, significant numbers of French and Portuguese fishing crews crossed the Atlantic each spring to harvest the lucrative resource, with English and Spanish fleets following shortly thereafter. The migratory fishery became an enduring enterprise, which lasted for more than three centuries before finally giving way to a resident industry in the 1800s.

Cod and the European Economy

Reports that Newfoundland and Labrador's waters were rich in codfish were of interest to European governments for a variety of reasons at the turn of the 16th century. France, Portugal, and Italy all lacked sufficient supplies of protein for their populations, creating a demand for fish and meat imports on domestic markets. Cod was a good source of protein that preserved well and was easy to transport. Further, commercial fisheries were already an important part of the European economy and merchants could find buyers for new cod imports with relative ease by using existing trade networks.

The European economy was also well-positioned to receive new fish imports by the early 16th century. With its population rising and economy expanding — due in part to prosperous agriculture and manufacturing industries — the continent was capable of financing expeditions to distant fishing grounds, while its public had money to spend at the marketplace. Strong demand drove up the price of fish, which further motivated merchants and governments to maintain the supply. Europe's economy continued to prosper until about 1620, giving the migratory fishery much time to develop.

The transatlantic fishery further helped the European economy by creating jobs for workers directly and indirectly involved in the harvesting of fish. Alongside the thousands of people who travelled to Newfoundland and Labrador each year were the many more who manufactured nets, hooks, barrels, salt and other goods associated with the catching, processing, and packaging of fish. Other workers found employment with merchant firms selling cod to domestic and foreign markets. Alongside its economic benefits, the migratory cod fishery also became attractive to many European governments as a means of supplying skilled seamen to their navies and armadas.

Participants in the Fishery

Although the migratory fishery was itself a long-lived industry — lasting for 300 years — the makeup of the individual nations engaged in it changed over time. The French dominated the fishery throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, while the English gradually grew in importance to become the industry's primary participant during the 18th century. Other fleets, primarily Portuguese and Spanish, engaged in the migratory fishery at various times in its history, but never to the extent the French and English did while at their peaks.

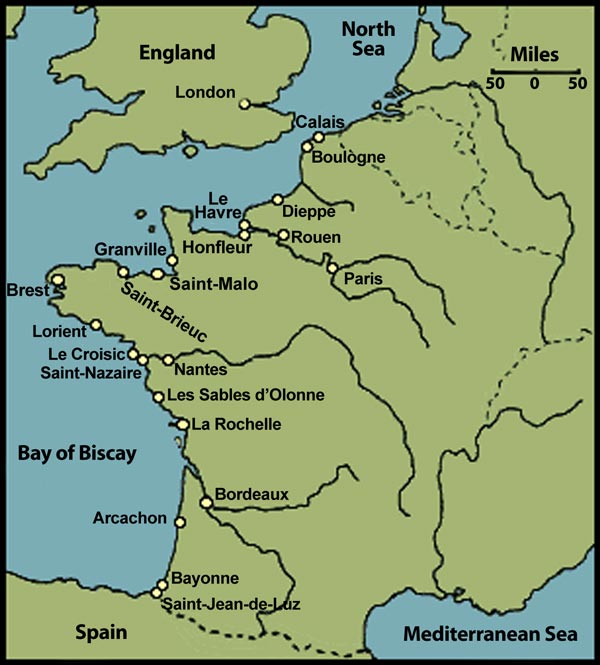

France's early dominance resulted in large part from the geographical proximity of its seaports to Newfoundland and Labrador; its existing domestic and foreign markets for cod; and the experience of its fishers in catching cod in the North Sea. Most fishers came from either Brittany or Normandy, which were located on France's northwest coast and therefore ideally situated to exploit Newfoundland and Labrador fishing grounds. By 1508, both Breton and Norman vessels were annually crossing the Atlantic for cod in increasing numbers.

Portuguese fleets were also engaged in the transatlantic fishery at this time, although in smaller numbers than their French counterparts. After about 1540, Basques fishers from northern Spain began to regularly visit Newfoundland and Labrador waters, but ended this practice in the early 17th century, due in large part to Spain's war with England. This conflict, which lasted from about 1585 to 1604, monopolized much of Spain's maritime resources and handicapped its ability to send vessels and fishers overseas.

Migratory Basque whalers from France and Spain also arrived at Newfoundland and Labrador during the 16th century to hunt right and bowhead whales in the Strait of Belle Isle. Most operated from Red Bay and other harbours in southern Labrador, where they remained from July through January. Up to 30 Basques ships annually arrived at Labrador, with each vessel carrying a crew of up to 130 whalers. Although a lucrative industry, the whale hunt ended in the early 17th century, due in part to decreased whale stocks resulting from over hunting, and the Basques concentrated their efforts on fishing.

England's participation in the migratory cod fishery was limited for much of the 16th century. Unlike France, its primary fishing ports were located on its northeastern coast, which allowed for easy access to fishing grounds in the North Sea, but were poorly situated to access Newfoundland and Labrador waters. Further, English markets for cod were not as large as French ones, allowing the country's domestic and Icelandic fisheries to satisfy most of its demand for the product.

West Country Ports

Spain's withdrawal from the fishery left Mediterranean markets with a decreased supply of cod and created new opportunities for foreign fish merchants. England was at this time well positioned to increase its participation in the industry. Its Icelandic fishery declined after 1580, in large part due to new license fees imposed by the Danish government, creating interest among English fishers and merchants in Newfoundland and Labrador cod stocks. As a result, seaports on the country's northeast coast decreased in activity, while those to the southwest — in an area known as England's West Country — grew in importance.

New markets in the Mediterranean, coupled with the West Country's proximity to Newfoundland and Labrador, resulted in England's increased participation in the transatlantic fishery. Vessels departing West Country ports had a shorter distance to cover than their French competitors, giving them a valuable advantage in securing favourable fishing grounds and campsites at Newfoundland and Labrador.

By the early 1600s, France and England dominated the migratory fishery, with the French fleet outnumbering the English by about two vessels to one for most of the century. Differences between the two nations' fisheries, however, reduced the risk of conflict during this period. Each, for example, worked from separate areas of Newfoundland and Labrador: the English established operations on the Avalon Peninsula and in Bonavista Bay, while the French fished from the island's north and west coasts, as well as from Placentia and Fortune Bays. Both nations also processed cod in different ways — France employed a "wet" cure that involved heavily salting cod and packing it in brine, while the English lightly salted and dried their fish on flakes, resulting in a "dry" cure.

The 18th century, however, brought great change to the transatlantic fishery. The Treaty of Utrecht granted Britain sovereignty over Newfoundland in 1713 and forced French fishers off most of the island. Although France retained seasonal fishing rights to the coast between Cape Bonavista and Pointe Riche, its involvement in the fishery continued to decline. England, on the other hand, steadily increased the number of vessels it sent to the island each spring and ultimately became the foremost participant in the migratory fishery, as well as in the development of Newfoundland and Labrador's economic, social, and political future.