Archaeology at Ferryland

There are a number of ways to discover the past: the study of documents written about past events (traditional history), oral traditions about the past (oral history) and the study of objects lost, abandoned or discarded by past societies ( archaeology). Each has its advantages and disadvantages and the information derived from each set of techniques might be said to come to us through a set of filters.

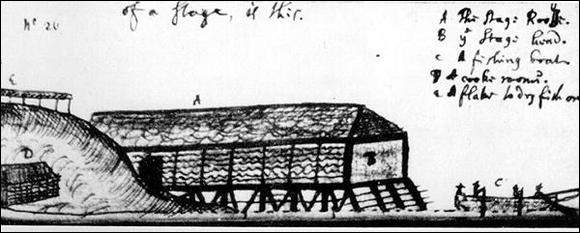

Many letters and other records written in the 16th and 17th centuries have not survived. Only a small percentage of the population was literate. They selected what they chose to write about and often had particular purposes for their writings. For example, a letter from Edward Wynne, Avalon's first governor, lists the names of the settlers who wintered there in 1622/23 , and the journal of James Yonge, a 16-year-old surgeon who summered in Newfoundland in 1663, explains the share system used by fishermen.

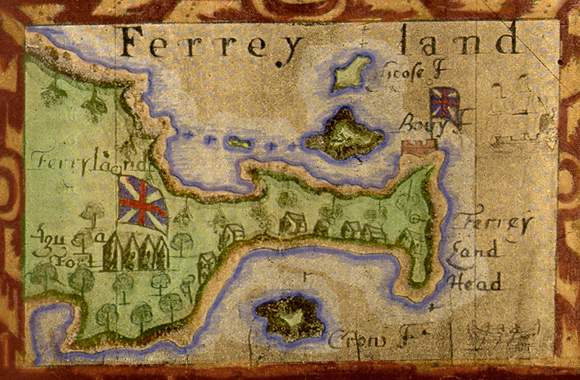

While neither oral history nor archaeology might be expected to provide such information, written sources are remarkably silent on such topics as the appearance of Avalon and the Pool Plantation, the location of the settlers' cemetery and so forth.

Oral history, while occasionally remarkably accurate, is likely to be distorted over hundreds of years, and some stories are simply forgotten. At Ferryland there are several versions of a legend about a long-lost well, with a different location for each over an area of several acres. One version, however, proved accurate and pointed out the precise location of the well. Another tradition states that Lady Kirke is buried "somewhere on the Downs," a large cleared peninsula east of the settlement.

Archaeological evidence also is filtered during that period between the time objects are lost, discarded or abandoned and the time they are revealed by careful excavation. Organic objects — those made from wood, bone, antler, leather, ivory, textile, for example — disappear within a century in most areas of Newfoundland. While archaeology is selective in this way, it is not selective in whose remains are preserved. At Ferryland, refuse discarded by the most humble fishing family, never mentioned in historical records or remembered in legend, stands as much chance of being preserved as does refuse discarded by the gentry of Avalon and the Pool Plantation.

Documentary sources related to Ferryland have already been compiled. Oral traditions have been recorded. Barring some completely unforeseen discovery, we probably know all we can learn from these sources. Evidence from archaeology, on the other hand, continues to be revealed each summer as new structures and thousands of artifacts are discovered.

When this new information is interpreted and added to existing knowledge, of whatever kind, the result is an ever-changing and ever-increasing understanding of the settlement of Ferryland from the early 1500s until the present day.