The Truck System

Newfoundland and Labrador’s outport economy depended not on cash, but on merchant credit for much of the nineteenth century. Each fall, fishers traded their annual harvest of salt-cod to local merchants for clothes, food, fishing gear, and other supplies from their stores. Fishers often received these goods earlier in the year on credit, but did not know the price at which they purchased them. Merchants set the price for goods taken on credit at the end of the fishing season, balancing the prices of goods against the prices merchants would get for fish in international markets. Such price manipulations maximized the opportunity for merchants to profit from the fish trade, but left their clients with the prospect of simply breaking even or falling into deeper debt each season.

Known as the 'truck' or 'credit' system, the price manipulations of this particular cashless exchange had advantages and drawbacks for all parties involved. Merchant credit helped fishers withstand poor fishing seasons and provided them with goods they could not produce locally, such as molasses, tea, and nails. However, many fishers could not catch enough cod to pay off their credit and sometimes fell into deeper debt each year. Some merchants also exploited fishers by charging too much for goods and paying too little for fish. The merchants, meanwhile, had a guaranteed clientele through the truck system, but had to absorb any losses when the cod fishery failed or when fishers failed to pay debts.

The truck system emerged in Newfoundland and Labrador in the early nineteenth century, when a resident fishery replaced the English migratory fishery. It was not unique to the colony and had existed in parts of Britain, for example, since at least the fifteenth century. Credit-based economies appeared most commonly in rural mining, fishing, farming, and logging communities where cash was scarce and where only a very limited variety of locally produced goods existed to meet residents' needs.

Fishers and the Truck System

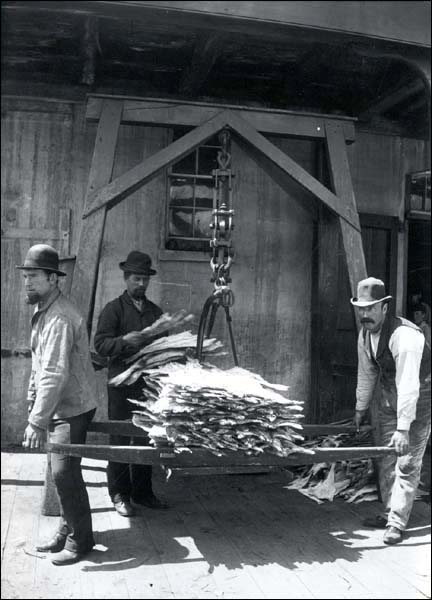

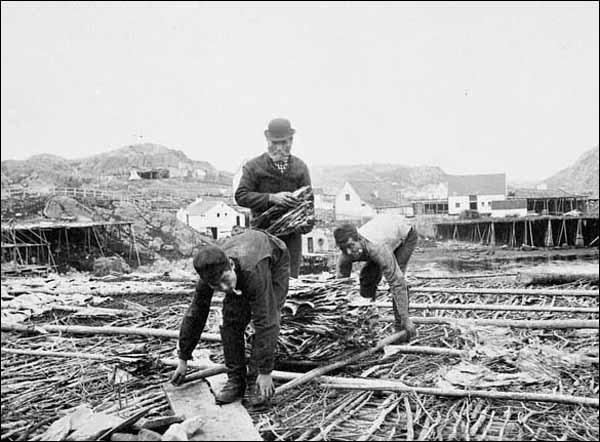

Each spring, Newfoundland and Labrador fishers – which included inshore, Labrador, and Bank fishers, as well as planters, their servants, and small-scale independent fishers – received supplies from a local merchant to outfit their boats for the summer fishery and to provide for their families in the coming months. The merchant delivered these goods on credit and recorded how much each fisher owed. In return, fishers and their families spent the summer catching and salting cod, which they gave to their merchants as payment in the fall. A culler then graded the catch to determine how much it was worth and how much the merchant should subtract from each fisher’s debt. Fishers left with a credit could obtain more supplies to get through the winter, while those in debt could only receive winter supplies at the merchant's discretion. Those that did not receive additional credit often had to seek government relief or help from a charity.

How much money the cod could fetch, however, changed frequently and depended on international demand, the availability of cod on the market, and a variety of other factors. As a result, fishers rarely knew how much their catches would be worth before handing them over to merchants. Compounding the situation was the manner in which cod was graded. The cullers who determined how much the fish was worth were on the merchants' payrolls and it was therefore in their interest to provide their employers with the lowest possible price. Some fishers felt cullers intentionally undervalued their fish.

Merchants also determined how much to charge for any supplies they traded for saltfish. This contributed to existing tensions, as many fishers suspected merchants of charging too much for their own supplies while simultaneously paying too small a price for cod. Although the local press and at least one politician – conservative James Winter – reported in the late nineteenth century that merchants priced their supplies about 40 per cent above their cash value, it is unclear how accurate this estimate is.

Fishers who believed they were being treated unfairly were often unable to negotiate a better arrangement with a different supplier because most outports were serviced by a single merchant. If more than one merchant worked in a community, they usually agreed on a common price for fish each season. However, discontented fishers could challenge the merchants in court if they wished and such wage disputes were common in the nineteenth century.

Merchants and the Truck System

Earning a profit under the truck system was difficult for merchants as well as for fishers. This was largely due to the uncertain nature of the fishery – some years the cod were plentiful, other times they were scarce. During the bad years, merchants often helped fishers by over-extending their credit. They compensated during the good years by marking up the price of goods they traded for fish. This also helped merchants absorb any unpaid debts and cover the costs of marketing and shipping fish to international buyers.

Although some merchants abused the system, there were also fishers who tried to cheat the merchant. Some used fishing gear they had obtained from a local merchant on credit to secretly work for St. Pierre merchants or sell bait to American Bank fishers for cash. Others intentionally produced a low-grade cure because they felt the merchants would undercut their wages no matter what quality of fish they traded. As a result, it became difficult for some merchants to obtain high prices for their fish in the marketplace.

The truck system created a complex and often tense relationship between fishers and merchants. Both depended on the other to earn a living, yet each often suspected the other of exploiting the system for his or her own benefit. Although it was widely believed during the 1800s that the truck system trapped fishers in a cycle of debt and stifled outport economies, merchant credit also provided rural inhabitants with a variety of resources they would not otherwise have access to; it also helped them withstand poor fishing seasons, provided that merchants did not restrict their credit.

Nonetheless, much of the bargaining power lay with the merchant under the truck system. Fishers had to depend on the value of their catch to obtain supplies, but rarely knew how much their cod would fetch in a fluctuating international market. They also lacked sufficient resources to support themselves without merchant credit, but exactly how much they earned depended on the merchant’s calculations. Moreover, some merchants began restricting credit by the mid-1800s because of a declining market. This forced many fishers to seek government relief and plunged them into deeper poverty.