19th Century Cod Fisheries

The salt-cod fishery was a mainstay of Newfoundland and Labrador's economy throughout the nineteenth century. It consisted of three branches: an inshore fishery off the island's coast, a Labrador fishery, and an offshore bank fishery. Of these, the inshore fishery was both the oldest and largest, with roots in an English migratory fishery dating back to the 1500s. Over-exploitation of cod during the 1800s, however, helped force the inshore fishery into decline. To maintain exports, the country introduced more efficient fishing gear and expanded its efforts into waters off the Labrador coast and on the Grand Banks.

Inshore Fishery

The Napoleonic and Anglo-American wars of the early 1800s helped turn the inshore Newfoundland and Labrador fishery into a resident rather than migratory industry. As the French and American fisheries declined between 1804 and 1815, Newfoundland and Labrador cod became more valuable on the international market. This prompted many more English and Irish fishers to permanently settle on the island instead of traveling there each summer to fish. Most of these men and women established settlements along Newfoundland's northeast coast and Avalon Peninsula, and some also migrated to the island's French Shore each year to catch codfish in those waters as well while hostilities disrupted French fishing effort there.

The inshore fishery was a seasonal, family-based industry. Fishers, usually men, left their homes early each morning to row or sail to nearby fishing grounds in small boats. Most fished for cod using handlines – a fishing line with a hook attached to one end. Fishers baited the hook with squid or capelin, dropped it in the water, and pulled the line up and down to attract cod.

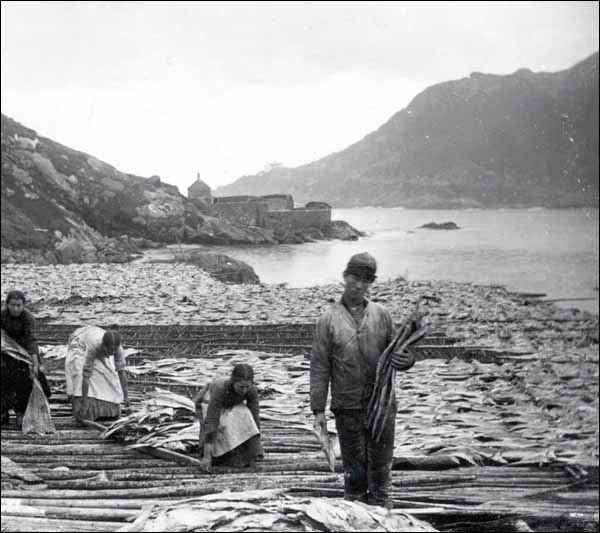

When the men returned home, the entire family helped cure the catch. Mothers, wives, daughters, and sons helped remove the cod's head, spine, and guts before salting the fish and laying it out on wooden flakes to dry in the sun. The drying process could take weeks and the family had to bring the product inside whenever it rained. Fishing people traded their salt cod to merchants to pay for gear and supplies they had previously obtained on credit.

The wartime prosperity of the early 1800s resulted in a near doubling of Newfoundland and Labrador's population, which jumped from 21,975 in 1805 to 40,568 in 1815. The colony's fish exports also increased accordingly, rising from 625,519 quintals (1 quintal = 50.8 kilograms) to almost 1.2 million during the same time period. When hostilities ended, however, the price of cod dropped dramatically and resident fishers had to increase their catch or branch into the seal fishery to make up for declining incomes and to maintain exports.

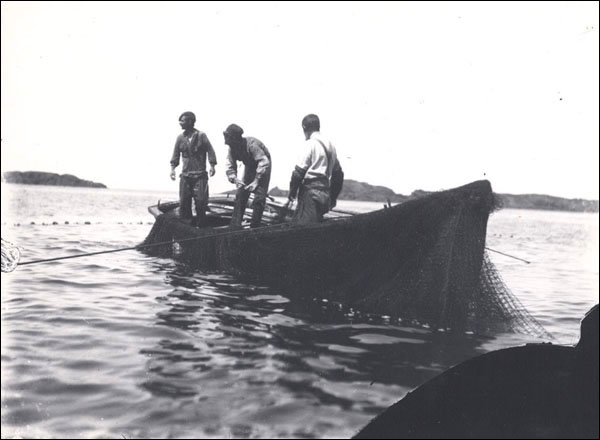

As the rising population caught larger volumes of fish, however, it placed a growing strain on local cod stocks. This was evident in the colony's salt-fish exports – although more people were fishing, the colony's exports fluctuated throughout the 1800s instead of increasing accordingly. Cod became scarce in areas where people had been fishing the longest, such as within Conception, Trinity, and Bonavista Bays. To compensate, some fishers adopted more efficient gears, including cod seines (large nets which fishers towed from their boats to encircle entire schools of codfish), trawl lines (hundreds of baited hooks attached to long fishing lines), gillnets (large nets used to entangle fish), and cod traps (large, box-shaped stationary nets that, once fixed in the water, fished while unattended).

Some fishers also increased their effort by area, moving from fishing grounds within the island's large bays to those on outer headland areas. These outer headland fisheries required larger vessels, such as jack boats or bulleys (small schooner-rigged vessels, measuring 25 to 30 feet long and weighing between five and 20 tons).The larger vessels and newer gears, however, were expensive and the majority of fishers could not afford to use them. Fishers who did use the new equipment caught larger volumes of fish in less time that the traditional hook-and-line method and created more intense competition on the fishing grounds.

As the new equipment became more widespread in the mid-1800s, many inshore fishers began to protest their use. Some argued the gear left too few fish behind for handliners, who could neither compete with nor afford the intrusive equipment; others worried the new technologies were depleting inshore cod stocks. Government inaction compounded the handliners' discontent and a frustrated few began to sabotage seines and other gear. Eventually, however, other fishers either had to adopt the gear out of necessity or, if they could not afford them, work for those who had adopted them, recognizing that few jobs existed on the island outside the fishery.

The Labrador Fishery

Following the post-1815 depression, increasing numbers of fishers began migrating from Newfoundland to Labrador each summer to fish there as well. The Labrador fishery served two purposes: it provided a use for sealing vessels in the off season and allowed fishers from bays where the cod stocks were depleted to still earn a living. However, only fishers who possessed schooners, jack boats or bulleys were able to travel north, and those who did had to spend weeks or even months away from home. As a result, some fishers brought their families with them; this was both for company and to help cure the catch.

The Labrador fishery consisted of two groups: stationers and floaters. Islanders who set up living quarters on shore and fished each day in small boats were known as stationers, while floaters lived on board their vessels and sailed up and down the Labrador coast, often travelling further north than stationers. Floaters packed their fish in salt and brought it back to Newfoundland at the end of each season to be dried there, while stationers salted and cured their fish on shore shortly after catching it. Both methods had their drawbacks. Labrador's damp weather often resulted in a poorer cure, while floaters risked damaging their catch during the long voyage home.

By the mid-1860s, the cod fishery on Labrador's southern coast was producing only small amounts of fish. To compensate, some fishers began using more efficient gear, particularly cod traps, while others traveled further north to find new fishing grounds. The northward expansion, coupled with the use of new gear, for a time resulted in larger catches and allowed the colony to maintain or increase its exports. Some historians argue that this pattern masked an ecological imbalance between fishers and cod – as the discovery of new fishing grounds bolstered exports, it became less apparent that older grounds had been over-exploited (Cadigan and Hutchings). The Labrador fishery fell into serious decline in the 1920s and eventually disappeared altogether.

The Bank Fishery

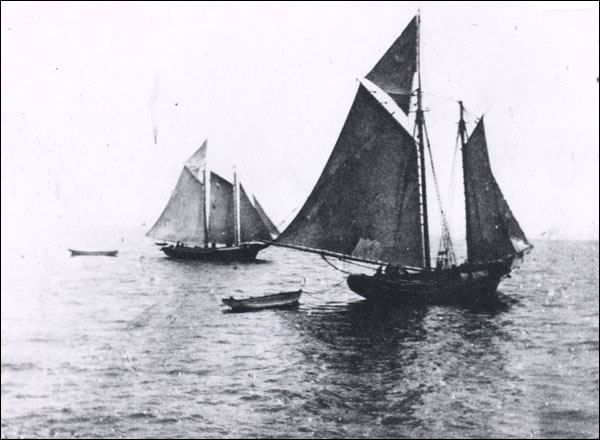

As the Labrador and inshore fisheries declined throughout the 1800s, the Newfoundland and Labrador government encouraged fishers to travel to the Grand Banks by offering them subsidies. By the mid-1870s, fishers were arriving on the Banks in wooden schooners, sealing steamers, and other vessels that weighed between 20 and 250 tons. The bank fishery typically ran from March until October, but fishing schedules could vary between different communities. Fishers living on the island's northeast coast, for example, often had to wait until April or May to leave because of ice on the water. Vessels made three or four trips to the banks each season, and remained there for weeks before returning home.

After arriving on the banks, crews anchored their boats in a favourable location and launched dories into the water. These small boats carried two or three crewmembers who fished for cod using handlines, jiggers, or trawl lines (also called bultows). The fishers left the larger boat each morning, rowed to various fishing grounds, and returned several times throughout the day to unload their catch. They also gutted, split, and salted their own fish.

Fishers engaged in the bank fishery faced a number of dangers. Gales and rough weather threatened schooners and other banking vessels, while dory crews risked becoming lost in fog or storms. Large ocean liners also frequented the banks and could inadvertently capsize or run down dories and schooners in foggy weather. Living quarters were often cramped and any injured or ill crewmembers would usually have to wait until landing at port to receive proper medical attention.

The offshore fishery was profitable throughout the 1880s and peaked in 1889, when 4,401 Newfoundland and Labrador fishers harvested more than 12 million kilograms of cod. The industry fell into decline in the 1890s and landings continued to decrease. By 1920, many communities had stopped participating in the bank fishery altogether.