1894 Bank Crash

On 10 December 1894, two of Newfoundland and Labrador's three banks closed their doors and never opened them again. The impacts were immediate and widespread – businesses collapsed, workers became suddenly unemployed, families lost their savings, and the country, which used the bank notes as its main source of currency, was left with no reliable circulating medium.

Although the crash caught most people off guard, it was the result of many years of reckless banking amid a troubled fishery and declining economy. The banks depleted their own holdings to loan large sums of money to fish merchants already in debt and in turn had to borrow from other financial institutions. The process left the banks dependent on outside loans – if a crisis disturbed the process or if the banks' credit deteriorated, then they would be forced to close. This was the case on Black Monday, when the Union and Commercial Banks ceased operations permanently.

Newfoundland and Labrador Economy before the Crash

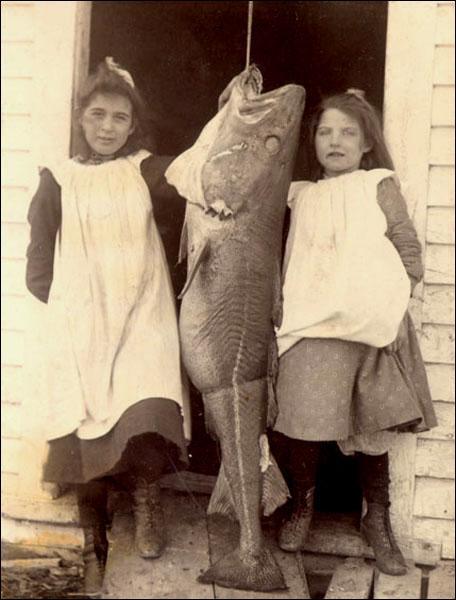

The salt-cod fishery was a mainstay of Newfoundland and Labrador's economy throughout the 1800s. Fishers traded their catch to merchants for credit in their stores and the merchants exported fish to Europe, South America, and the Caribbean. Many fishers, however, could not catch enough cod to pay off their credit and fell into deeper debt each year. Some tried to subvert the process, known as the truck system, by selling fish directly to foreign buyers for cash or by giving their merchants poorly cured fish.

Although the fish trade was profitable throughout much of the 19th century, it encountered difficulties in the 1880s. An overabundance of saltfish on the international market caused prices to drop, while competition from French and Norwegian fishers further cut into Newfoundland and Labrador's profits. This was exacerbated by the low quality cure of the country's fish, which acquired a bad reputation overseas and made its sale even more difficult.

Shrinking profits forced the country's merchants and fishers into deep debt. By 1894, for example, Notre Dame merchant Edwin John Duder loaned about $400,000 in credit to fishers who would likely not be able to repay their debts. A rapid increase in the country's fishing population during the second half of the 19th century placed a further strain on the merchants, who had to deal with rising numbers of fishers seeking credit.

At the same time, many of the country's most experienced merchants died or reached the age of retirement in the late 1800s and their withdrawal from the fishing industry left it with considerably less working capital. After merchant John Munn died in 1879, for example, his firm had to pay large sums of money to his wife and children, leaving Munn's business successors with considerably less funds to work with.

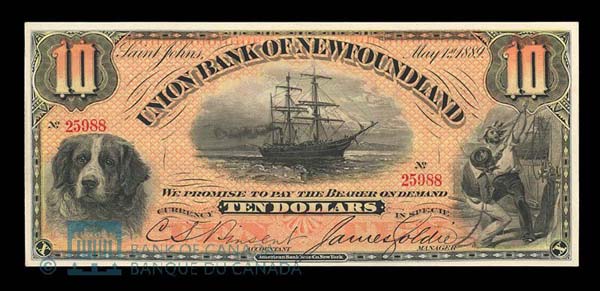

To keep the fishing industry afloat and cope with mounting debts, many merchants applied for and received sizeable loans from the country's two private banks. In the years leading up to the crash, the Union and Commercial Banks loaned millions of dollars to fish merchants without recovering the bulk of their investments. This was the result of a virtually unregulated banking system in which the very merchants who borrowed money from the banks also sat on their boards of directors.

Merchant Bank Directors

Three banks existed in Newfoundland and Labrador at the time of the crash – the Newfoundland Savings Bank (opened in 1834), the Union Bank (1854) and the Commercial Bank (1857). While the government operated the Savings Bank, both the Union and Commercial Banks were privately owned. Fish merchants sat on the boards of directors of both institutions and had much control over their day-to-day operations. As a result, the merchants were able to approve a series of large loans to themselves regardless of their credit ratings.

This practice continued for years without any external audits or other impartial checks. Although both banks released annual statements, they contained only the bare minimum of information. By 1894, the Union and Commercial Banks had loaned a combined $2.5 million to their merchant directors. Among these was Duder, who reported a surplus of $128,000 in 1882, but owed the banks $668,676 by 1894. As their own cash reserves became depleted, both banks borrowed heavily from the Savings Bank and various London banks.

In addition to loose banking practices, government policy and natural disaster also encouraged the Union and Commercial Banks to extend credit. The building of the Newfoundland Railway poured large sums of money into the local economy, making it easier for the two private banks to obtain large loans from the government-run Savings Bank. The Great Fire of 1892, which saw much of St. John's go up in flames, also injected about $7 million in insurance claims into the city's economy. Much of this flowed through the banks, temporarily buoying their cash reserves and allowing the directors to continue borrowing.

Despite these illusions of prosperity, the banks were in dire financial straits. They lacked sufficient cash reserves of their own to meet business obligations and became increasingly dependent on outside loans. This made them vulnerable to external factors over which they had no control – if an unforeseen event disrupted their ability to obtain credit abroad, the banks would not be able to continue operating.

Bank Crash

On Saturday, 8 December 1894, news reached St. John's that the firm of Prowse, Hall and Morris, London agents of Newfoundland and Labrador fish merchants, halted business following the death of one of its partners, Henry Hall. This prompted the London banks to suspend credit to the Commercial Bank of Newfoundland and request payment on some of its loans. The Commercial was unable to meet these demands and called upon its mercantile customers to repay their debts, but with no success – the merchants were under deep financial strain themselves and could offer the bank nothing but codfish.

Incapable of meeting its business obligations, the Commercial closed on 10 December 1894, a date widely known as Black Monday. Worried depositors immediately began to withdraw large sums of money from both the Union and Savings Banks. The Savings, however, had priority on all funds at the Union and quickly cashed a large cheque there to meet demands from its clients. This allowed the Savings to remain solvent, but forced the Union to close just hours after the Commercial; neither bank opened again.

The closures devalued the country's currency, halted business for most merchant firms, and left thousands of people unemployed. Many rural families, however, rebounded later that year because of a profitable spring seal hunt and summer cod fishery. The quick arrival of several Canadian banks on the island in late 1894 and early 1895 also did much to ease the crisis, as did the country's adoption of Canadian currency, still in circulation today.