St. John's and the Central Slum

By 2011, the city of St. John's was undergoing a period of rapid development, with rising property values and large amounts of residential and commercial construction. Housing conditions, prices, and availability still varied throughout the city, however, and rapidly rising purchase and rental prices were putting increased pressure on low-income groups. Although certain neighbourhoods (justifiably or not) had reputations for poor housing, there was no specific area of the city that was the subject of a public outcry about its conditions, and there were no readily identifiable "slum" areas.

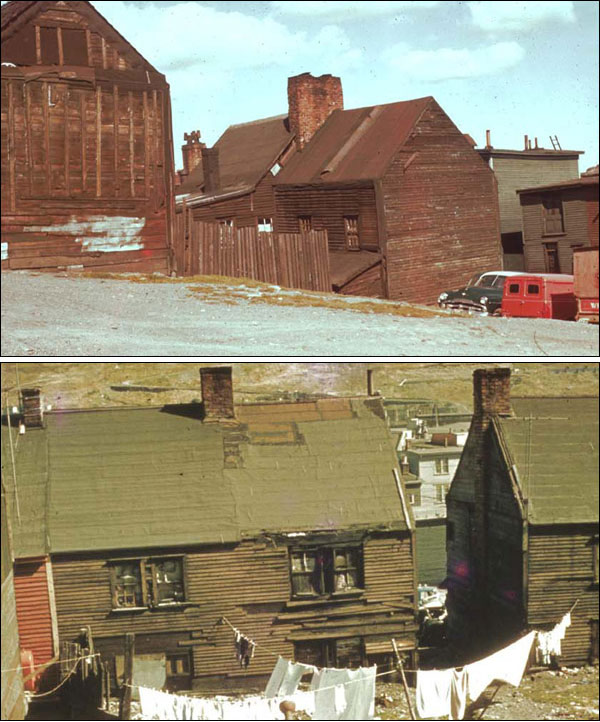

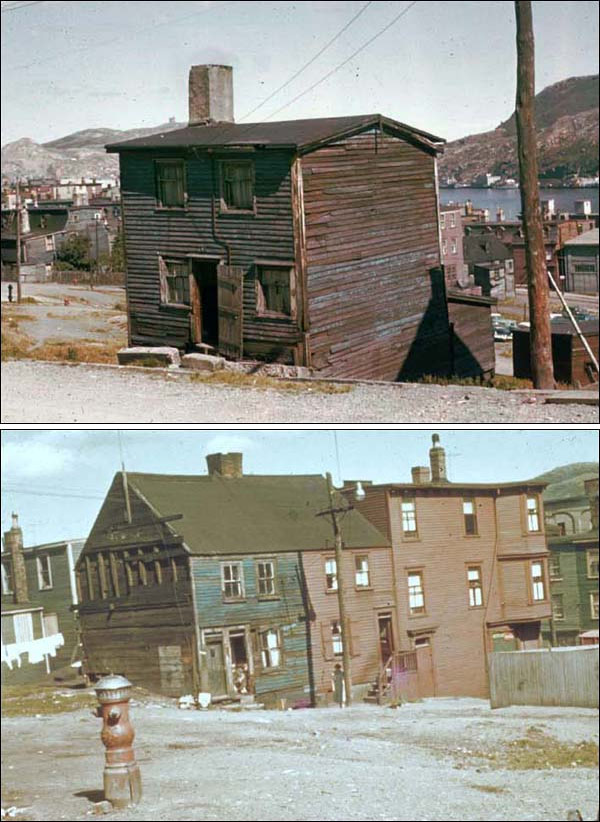

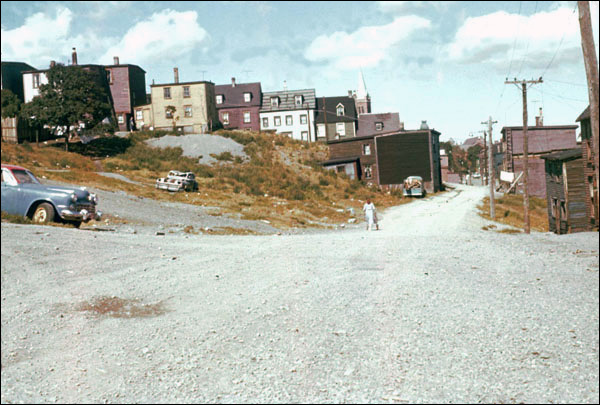

This was not always the case. For a period of at least 70 years, there was a slum area in the centre of St. John's. Bounded roughly by Springdale Street in the west, New Gower Street in the south, Carter's Hill in the east, and LeMarchant Road in the north, this area consisted mainly of old, ramshackle housing with poor sanitary services. Water was supplied from community taps, and night-soil collectors were common. There were well over a thousand homes in the area, most of them in need of replacement. Overcrowding was also a major problem. A 1942 survey found that there were 750 houses in St. John's in need of immediate or rapid demolition, the majority of them in the downtown slum. They housed about 6200 people, with an average of about 2.5 people per bedroom. To put this in perspective, the London County Council (responsible for providing public housing in London, England, at this time) recommended a maximum density of 1.25 people per bedroom.

Slum Origins

Although it was mostly outside the fire zone, the slum began to develop after the 1846 fire. Given the pressure to rebuild, many ramshackle houses were constructed quickly, very close together, and without proper building standards. The 1892 fire worsened the situation. Again the area escaped destruction, so that old houses remained and there was no rebuilding. People made homeless by the fire moved into the area, exacerbating the overcrowding and creating the conditions that turned this section of the city into an obvious slum by the turn of the 20th century. Although public concern over the crowded and unsanitary conditions was developing, there were no immediate attempts to improve the situation.

Early Attempts to Improve Housing

In 1910, a government report found that the city contained “a very large number of tenements [that] are totally unfit for human habitation. They are so bad that they cannot but degrade those who live in them physically, mentally, and morally.” The report referred specifically to the central slum district, an “eyesore” where poor housing conditions were damaging to the health and welfare of its residents, leading to high mortality rates, tuberculosis and other diseases. It was also believed that living in such conditions was morally detrimental, especially to children, and that criminal and deviant activity would result. Later reports were concerned specifically with the lack of privacy, especially in cases where male and female children had to share living and sleeping arrangements.

Despite the recognition of the problem, efforts to improve housing conditions in St. John's and clear the slum were slow and largely ineffective. Most people living in inadequate housing could not afford to pay the higher rents charged by properties in better areas, nor could they reasonably hope to save enough money to purchase or build their own homes. Residents of the slum who were better off still had limited options due to the scarcity of land available to build upon, and a general lack of available better housing. Some residents moved outside the city limits and built houses in areas such as Blackhead Road, Southside Road, and Mundy Pond. People were already living in these areas by the early twentieth century, but they grew considerably during the Great Depression when, in addition to city residents, people from other parts of Newfoundland moved to the city in search of work. They continued to grow into the 1940s and 1950s as the city's population rapidly expanded and space became more valuable. These outlying communities did little to relieve the pressure on housing, however, and sometimes became little better than slums themselves.

Outside intervention and investment was obviously needed. But the colonial and municipal governments, as well as religious and social groups, were very reluctant to become involved in expensive public housing projects, believing instead that low-income groups should be taught to take care of themselves rather than depend on handouts. Nevertheless, several housing schemes were undertaken. In 1918, the city, under Mayor William Gosling, built 22 low-cost houses along Quidi Vidi Road, the only time the city was directly involved in providing affordable housing. These houses cost more than anticipated, and were too expensive for the working-class families they were meant to help. In 1920 the Dominion Co-operative Building Association, a housing project led by businessman John Anderson, former mayor Michael Gibbs, and LSPU President Jim McGrath, constructed some houses on Merrymeeting Road, but ran into the same problems. The Railway Employees Welfare Association (REWA) had more success, first by providing low interest loans and rental purchase plans, and then by constructing houses along Craigmillar Avenue, 123 of them by 1935. The REWA projects were successful largely because its members were railway employees with relatively stable and well-paid jobs. None of these projects offered any real relief for those in slum housing.

The city began to recognize that the housing problem was not going to be solved by small-scale initiatives or the private market, and commissioned reports by the Canadian urban planner Arthur Dalzell in 1926 and the landscape designer Frederick Todd (who had been involved in designing Bowring Park) in 1930. The onset of the Great Depression sidelined these reports and postponed constructive action while worsening the problems of poverty and housing.

Confederation and Slum Clearance

In the early 1940s, the local prosperity created by the Second World War meant that realistic housing projects could finally be undertaken. The city appointed a Commission of Enquiry on Housing and Town Planning (CEHTP) in May 1942. The Commission's reports and recommendations led to the development of Churchill Park (see Churchill Park article), the first major attempt to improve the city's housing conditions. Although Churchill Park was a successful suburban development, it did not solve the slum problem. Its houses were too expensive for those with low incomes, and the central slum survived.

Confederation in 1949 proved to be the catalyst for schemes that would finally provide low-cost housing projects and allow slum clearance. That year, the federal government announced major changes in its funding policy relating to public housing. The result was that the city could count on substantial financial support from the federal and provincial governments.

Federal/provincial partnerships made possible the building of hundreds of subsidized public housing units on Cashin Avenue, Empire Avenue, Anderson Avenue, and elsewhere. Many of these units (including the Empire and Anderson Avenue projects) were on land originally intended for the Churchill Park development, and most are still in existence today. Residents of the slum were slowly moved to the new housing projects, and by the late 1960s the downtown slum was finally emptied and the old houses demolished to make way for redevelopment.

After the Slum

What had once been a municipal eyesore quickly became a revitalized downtown area. A new city hall was opened in 1970. The Delta Hotel, the Cabot Building office tower, and the Sebastian Court housing complex were also constructed. New Gower Street was widened to form the beginning of the Trans Canada Highway, and Mile One Stadium, completed in 2001, and rebranded as the Mary Brown's Centre in 2021, became the final major addition to the area. Having been seen as an embarrassment the former slum became a centrepiece of the downtown area.