Language

From a linguistic perspective, Newfoundland and Labrador today is the most homogeneous province in Canada. The overwhelming majority of its residents (some 98%) speak English as their sole mother tongue. The province nevertheless has a rich linguistic history. Its Indigenous languages, not all of which continue to be spoken, represent the Algonquian (Beothuk, Mi'Kmaq and Innu) and Eskimo-Aleut (Inuktitut) language families. As one of the earliest areas of the New World to be discovered by Europeans, Newfoundland and Labrador have seen many European visitors to their shores over the past 1000 years, including speakers of Norse, Basque, Spanish, Portuguese, German, French, Irish Gaelic, and Scots Gaelic. All but French and Scots Gaelic, however, have totally disappeared, leaving few traces of their passage apart from often colourful place names and a small amount of vocabulary.

English

The English spoken in Newfoundland and Labrador contains many non-standard linguistic features--in pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, meanings, and expressions. Some of these features are the preservation of non-standard regional and social variants from parts of the British Isles (chiefly from southwestern England and southeastern Ireland). Others are merely the preservation of variants that were once acceptable or even standard in earlier stages of the English language. Still others result from innovations within the province.

The rather high degree of non-standard usage of English in this province is not surprising. Newfoundland and Labrador remained outside the mainstream of social, political, and economic development in North America throughout most of their history. By the time we joined Canada in 1949, our oldest English-speaking dialect areas had experienced about three hundred years of local development with minimal influence from Standard English. This had allowed a number of local linguistic subsystems to become well established, especially in pronunciation and grammar.

Major consonantal variation involves three distinct pronunciations of l, dropping and adding of initial h, pronunciation of th as t or d and loss of r. Sentences such as Give 'in to I for Give it to me show non-standard use of pronouns in the grammar.

Lexical variation includes many non-standard word forms and word meanings. Words of Irish Gaelic origin sometimes spread to English settlers when the latter Anglicized them through folk etymology (e.g., hangashore for aindeiseoir 'a wretch'). Two typical variations in word form are due to change in the order of adjacent sounds (e.g., haps for hasp) and addition or deletion of syllables (e.g., kellup for kelp or quite for quiet). Such usages as rig for 'clothing' and stern/starn for 'buttocks' reflect the generally nautical nature of life in the past.

Several traditional dialect studies show a high degree of regional variation, and sociolinguistic studies show that this variation can be due to social factors such as gender, age and social class. Studies of language attitudes indicate rather mixed feelings towards non-standard varieties of speech in the province. More specifically, the urban population harbours surprisingly positive feelings towards speakers of non-standard dialects.

French

Only one group of French speakers has had a long history of settlement in the province. At the end of the 18th century, French speakers-- primarily Acadians from Cape Breton and the Magdalen Islands--settled the Port-au-Port peninsula and St. George's Bay. By 1850, the population of this region was 80% French-speaking.

During the 20th century, this group underwent much cultural and linguistic assimilation, a process hastened by the lack of French-language education prior to the 1970s. Although French is no longer spoken in Stephenville, the remaining speakers on the Port-au-Port peninsula now have access to bilingual schooling, as well as to a number of services in French, including French-language media.

Irish Gaelic

Most Irish settlers came from southeastern Ireland in the first half of the 19th century. Though some of this group spoke Irish Gaelic and little if any English on arrival, there are few actual accounts of Irish being spoken in Newfoundland, or of Irish being passed on within families. Irish Gaelic disappeared from the island early in the 20th century, but has left a number of traces in Newfoundland English. These include vocabulary items such as scrob "scratch", sleveen "rascal" and streel "slovenly person," grammatical patterns such as the "after" perfect as in "she's already after leavin'," and pronunciation features such as the "light" Irish l in words like "hill" or "pole".

Scots Gaelic

From the middle of the 19th century, small numbers of Scottish families from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, drawn in search of agricultural land, settled the southwest corner of the island of Newfoundland, south of St. George's Bay. They brought with them their Scots Gaelic tongue. Some 150 years later, the language has not entirely disappeared, although it has no fluent speakers. Knowledge of Scots Gaelic today seems to be largely restricted to memorized passages, such as traditional tales and songs.

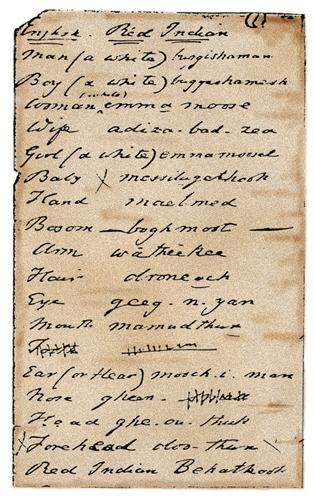

Beothuk

The small Beothuk group, which inhabited the island at the time of arrival of the first Europeans, became, after European contact, the victim of hostilities, disease and starvation. The last known speaker of Beothuk died in 1829 and today the language survives only in the form of three short vocabularies, separately elicited from three young Beothuk females by English speakers with no particular linguistic training, and riddled with errors as a result of repeated copying.

The result is that although there are sufficient similarities to lead some linguists to the conclusion that Beothuk was an Algonquian language, this conclusion will in all likelihood remain uncertain.

Mi'kmaq

The Newfoundland Mi'Kmaq are found on the west coast, in central Newfoundland, and in Conne River, Baie d'Espoir (the location of the Miawpukek Band). The 20th century has proven for the Mi'Kmaq a period of particularly rapid assimilation, involving loss of the traditional hunting and trapping lifestyle, as well as considerable intermarriage with non-Indigenous. The last fluent speaker of Mi'Kmaq died at Conne River in 1979, and today there are no fluent speakers within the province. It is, however, spoken as a first language in the Maritime provinces, and teachers from there have been assisting efforts by local Mi'Kmaq to revitalize their language.

Innu-aimun (Montagnais-Naskapi)

Today Innu-aimun, with approximately 1,600 speakers, is, after English and French, the most vigorous language in the province. In both Sheshatshit and Davis Inlet (Utshimassits), the vast majority of Innu families use the language at home. The young still speak it as a first language, although their vocabulary and the range of grammatical forms which they command is more restricted than that of their parents' and grandparents' generations. Within the local schools Innu-aimun has been used increasingly as the medium of instruction, although English is taught and used extensively as a second language for communication outside the community.

Labrador Inuktitut (Inuttut)

The province's Inuit are concentrated primarily in the three coastal Labrador communities of Nain, Hopedale and Makkovik. In all three communities, the Inuttut language is in serious decline. Among over 2,000 people of Inuit ancestry, just under 500 claim Inuttut as their sole mother tongue. Almost 300 of these live in Nain, where most are in the older age group. Even in Nain Inuit children rarely use Inuttut in their everyday interactions; English is becoming more frequent even in the home domain. The use of English as the medium of instruction in 20th-century Labrador has been a primary contributor, as of course has the general prestige associated with English-speaking society and culture.