Prohibition in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1917-1924

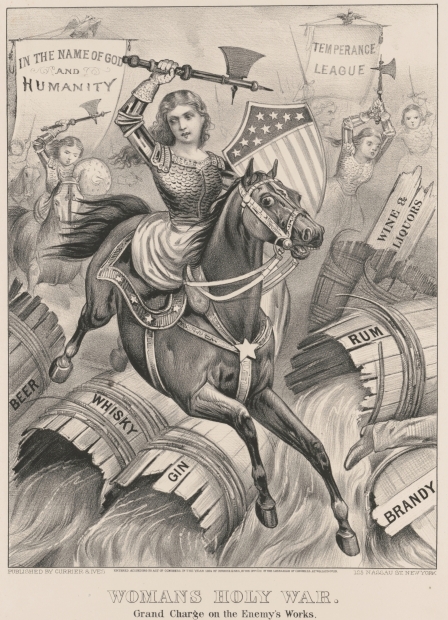

Prohibition in Newfoundland and Labrador was a dominion-wide ban on alcoholic beverages from 1917 to 1924. It grew out of an international temperance movement, which sought to curb or even eliminate alcohol consumption. Its followers argued that alcohol was responsible for many of society's problems, including spousal abuse, unemployment, and poverty.

The temperance movement gained ground in Newfoundland and Labrador during the second half of the 1800s. It was spearheaded by several groups, including the Sons and Daughters of Temperance, the Total Abstinence and Benefit Society, and the Newfoundland Temperance League.

In response to growing calls for prohibition, the Newfoundland government introduced a Temperance Act in 1871. The Act allowed electoral districts to hold local option elections on whether or not to ban alcohol within their borders. Local option elections allow voters in a specific electoral district to decide if their region will adopt a specific policy, like prohibition.

Under the 1871 Temperance Act, a ban on alcohol would pass if two-thirds of all eligible voters in the district supported prohibition. If the ban did pass, it would only apply to the district that voted in favor of prohibition and not to all of Newfoundland and Labrador.

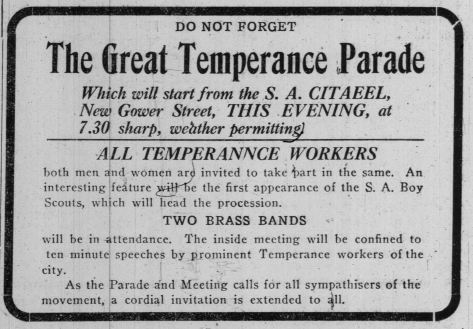

The local option elections revealed an overwhelming support for prohibition. By 1915, almost every part of the island outside of St. John's had voted in favor of prohibition. Temperance supporters argued it was time for the government to implement a dominion-wide ban on alcohol. They held two large public demonstrations in St. John's on April 20, 1915. The Women's Christian Temperance Union organized a march in the daytime, while the Salvation Army organized an event in the evening. More than 3,500 people attended the two rallies.

The next day, Prime Minister Edward Morris announced in the House of Assembly that the government would hold a plebiscite asking voters if they wanted dominion-wide prohibition. The date for the plebiscite was set for November 4, which was about six months away.

1915 Prohibition Plebiscite

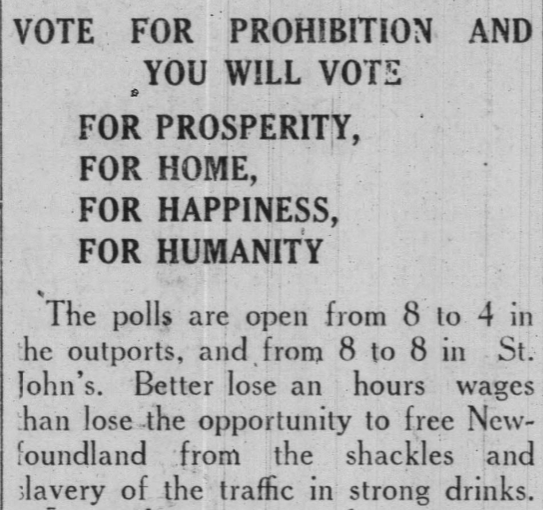

The question facing voters on November 4, 1915 was: "Are you in favour of prohibiting the importation, manufacture and sale of spirits, wine, ale, beer, cider and all other alcoholic beverages?" A yes was a vote in favor of prohibition.

Two conditions had to be met for prohibition to win: the majority of ballots cast had to support it, and that majority also had to equal at least 40 per cent of all registered voters-regardless of how many people came out to vote.

Eligible voters in 1915 were men, aged 21 and over who lived on the island of Newfoundland. Women were not allowed to vote. Neither were Labradorians, even though the outcome of the plebiscite would apply to all of Newfoundland and Labrador.

In the end, less than half of all registered voters took part in the November 4 plebiscite. However, an overwhelming majority of them voted yes. On November 26, the St. John's Daily Star reported that of the 30,324 votes cast, 24,977 supported prohibition. That number represented 40.6 percent of all eligible voters in the dominion. The one sixth of a percentage point that won prohibition amounted to 385 votes.

Prohibition was set to come into effect on January 1, 1917. Morris explained that the 13 months between the vote on prohibition and its implementation was necessary to "give a reasonable amount of time to those who engaged in the business to dispose of their stocks that they may have on hand, and to undertake some other occupation." It would also give the government time to prepare for the change.

Newfoundland was far from alone in its support for prohibition. It was also being implemented in much of North America. By 1916, many Canadian provinces were under prohibition, including PEI, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Alberta, and Ontario. By 1919, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, British Columbia, the Yukon, and Quebec had also banned alcohol. The United States introduced prohibition in 1920.

A Dry Dominion

On January 1, 1917, Newfoundland and Labrador became a dry dominion. Taverns closed their doors and beverages with an alcohol content of 2 per cent or greater became illegal. There were some exceptions, though. Alcohol could still be used for religious purposes, such as Holy Communion, and doctors could prescribe it for medicinal purposes. Anyone else caught in possession of alcohol could face a fine of between $100 and $500 or spend up to three months in prison.

Early newspaper reports indicated that a decrease in crime initially accompanied prohibition. Nonetheless, it soon became apparent that there was an open flouting of the new law and that many people were drinking illegally. Alcohol was obtained through four main strategies.

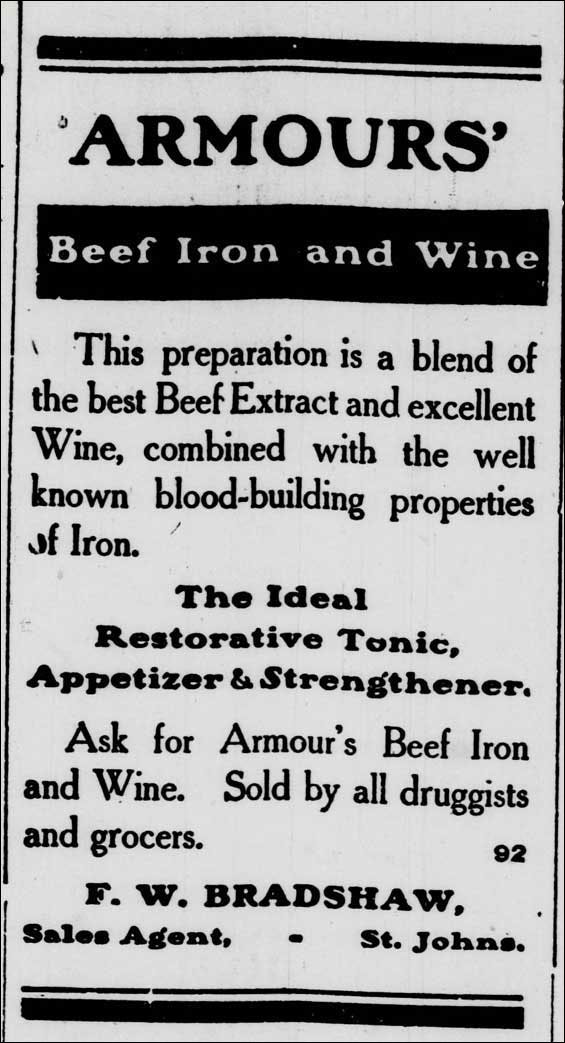

The first was patent medicines. Known popularly as dope, they were over-the-counter products that contained small amounts of alcohol-like cough medicines, hair tonics, health supplements, and flavor extracts. Popular products in Newfoundland and Labrador included Brown's Bronchial Elixir, a vitamin supplement known as Beef, Iron and Wine, and various flavourings, including Vanilla Extract and Essence of Lemon.

The Newfoundland Constabulary reported that patent medicines were a growing concern. In 1919, police arrested 228 people for being drunk and disorderly; 160 of those cases were due to dope. One year later saw the number of arrests rise to 276, of which 198 were due to patent medicines. In both years, dope accounted for about 70 per cent of arrests connected with drinking.

A second way that people circumvented prohibition was by making their own alcohol through the use of illegal stills, which condensed beverages with a low alcohol content into stronger drinks. Known as moonshine, these liquids not only broke the prohibition law, but also posed a serious health risk. The dangers were later reported on by a Royal Commission that investigated the effectiveness of prohibition in Newfoundland and Labrador:

"The fusil oil in moonshine has a definite poisonous effect, is bad for the nerve centres, will sometimes cause blindness and in the case of women and children the effects would be more pronounced and especially in the child. It certainly would have a bad effect on the progeny of those addicted to it."

The commissioners noted that moonshine and dope also led to an increase in violence:

"Another ugly feature shows itself by a comparison of the figures of 1916 and 1920. In 1916 less than one-third of those arrested were disorderly. In 1920 about half of those arrested were disorderly. This makes clear that the use of dope or moonshine creates far more disorder than the use of ordinary liquors."

Bootlegging was a third scheme that supplied the underground market with alcohol. Large quantities of rum and whiskey were smuggled into Newfoundland from the nearby island of St. Pierre during prohibition. The commissioners reported that this problem was so large, that the local police force could not keep up.

"Your Commissioners are of opinion that in order to successfully grapple with it, the detective force should be augmented. Its present strength is too inadequate for the constant vigilance necessary to cope with liquor smuggling. Special rewards might be offered to police and customs officers to stimulate their vigilance."

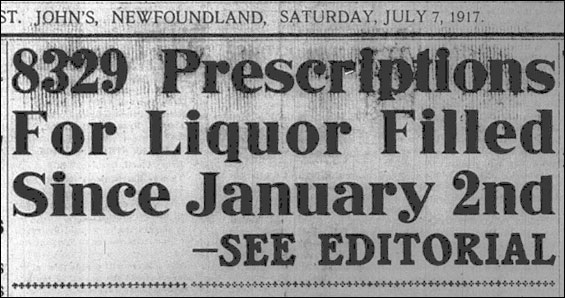

A fourth method of obtaining alcohol was through medical prescriptions, which were popularly known as "scripts" at the time. Doctors were permitted to prescribe alcohol for medical purposes during prohibition; they could also earn between $1 and $2 per script distributed.

The distribution of scripts increased during prohibition. Further, the Royal Commission that investigated prohibition found that a large portion of the liquor obtained through prescriptions was used for recreational instead of medical purposes.

"While your Commissioners are loath to suggest 'regulations' which would unduly interfere with the exercise of the discretion of the medical practitioner who honestly prescribes 'liquors' for medicinal purposes, they find there is need of a strong check to stop the loose giving out of prescriptions."

A Call for Change

A growing number of people soon believed that prohibition was a failure. Critics argued that the police did not have enough resources to properly enforce prohibition and that the policy had created more problems than it fixed. Alcohol was still fairly easy to acquire, smuggling and illegal stills were on the rise, and so were illnesses related to moonshine and other forms of unregulated liquor.

Although the problems with prohibition seemed easy to identify, there was much debate around how to fix the situation. In 1920, two opposing groups submitted petitions to the government. One called for a stricter form of prohibition, the other called for a partial lift of the alcohol ban. By then, Richard Squires was the Prime Minister of Newfoundland and Labrador. He responded by establishing a Royal Commission in August of 1920 to investigate prohibition.

The commissioners submitted their report in May 1921. For the most part, they were critical of prohibition and called for an end of the alcohol ban. To prevent the illicit manufacture of alcohol, the commissioners recommended tighter regulations regarding moonshine and bootlegging, and that the sale of alcohol be placed under government care, through the creation of a board of liquor control.

The report's recommendations were not acted upon until 1924, when a new government, led by Walter Monroe ended prohibition. The Monroe government also established a Board of Liquor Control to oversee the production and sale of alcoholic beverages. That board was the precursor of what is today know as the Newfoundland and Labrador Liquor Corporation.