Government Structure, 1832-1855

Newfoundland's system of representative government was bicameral in nature, which means it consisted of two legislative chambers – an appointed Board of Council (also known as Legislative Council) and an elected House of Assembly. Both served under a governor, who was appointed by the British government to represent the crown in Newfoundland. The governor named officials to the Council, while the public elected representatives into the 15-seat House of Assembly.

An Executive Council also existed to advise the governor and was composed of officials nominated by him. The governor often named the same group of people to both the Legislative and Executive Councils, although this changed when the Amalgamated Assembly came into power between 1842 and 1848. The Legislative Council had the power to pass laws, while the Executive Council decided on government policy.

The House of Assembly submitted bills to the Legislative Council, which either approved, rejected, or amended the proposed legislation. Amended bills returned to the Assembly for its approval. Although both chambers had to work together to be productive, sectarian tensions sometimes slowed government business. Members of the Council were predominately English, Protestant, and Conservative, while Liberals and Irish Roman Catholics held a significant number of seats in the House of Assembly.

The governor also possessed considerable power under the system of representative government. He nominated officials to the Legislative and Executive Councils, could prorogue the House of Assembly, had the power to stop any new legislation from becoming law, and could submit bills to the House for debate. The governor reported directly to the British Colonial Office, which oversaw all matters relating to England's colonial empire, and could therefore influence the manner in which Britain administered Newfoundland.

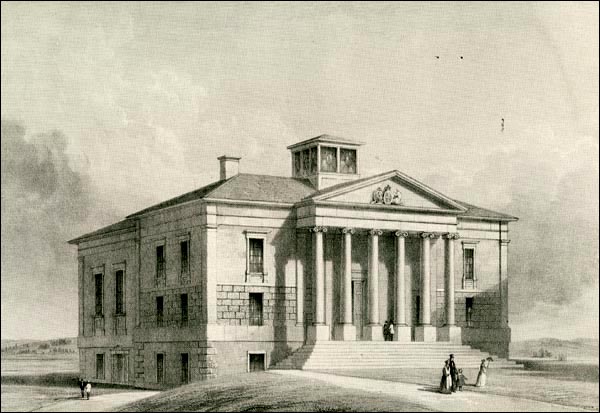

House of Assembly

The House of Assembly consisted of 15 representatives from nine electoral districts on the island of Newfoundland – Conception Bay, St. John's, Bonavista Bay, Trinity Bay, Ferryland, Twillingate-Fogo, Burin, Fortune Bay, and Placentia-St. Mary's. All districts had one seat in the House of Assembly, except for the more populous districts of Conception Bay, St. John's, and Placentia-St. Mary's, which respectively elected four, three, and two representatives.

Members of the public were eligible to run for political office if they were male British subjects, 21 years or older, and had lived in the colony as either tenants or homeowners for at least two consecutive years leading up to the election. The same qualifications applied to voters, except length of residence was reduced to a single year. Voting rights were not restricted by race, religion, social status, or wealth, which made Newfoundland's suffrage the broadest in the British Empire. Women, however, were not allowed to vote or run for office until 1925. Britain increased eligibility requirements for candidates in 1842, when it passed a bill stipulating that any person wishing to run for office had to earn a minimum annual salary of £100 or own property worth at least £500. The same bill increased the term of residence for eligible voters from one year to two.

During the period of representative government, Newfoundland had five general elections (1832, 1837, 1842, 1848, and 1852) and six by-elections to fill seats vacated by individual politicians for various reasons – usually death or appointment to the council. A general election also took place in 1836, but Chief Justice Henry Boulton declared its results null and void due to a legal technicality – the election writs did not bear the required Great Seal of the island of Newfoundland. As a result, a new election took place in 1837. Liberal candidates earned the majority of votes in every general election excluding the first. They won 14 seats in 1837 and nine in the 1842, 1848, and 1852 elections.

Legislative Council

The Governor of Newfoundland nominated members to the Legislative Council, who were then appointed by the British crown. Unlike the House of Assembly, which represented the voting public, the Council was answerable to the British government and not to the people of Newfoundland. The 1832 Council consisted of seven officials, which increased to nine in 1833 and to 10 in 1834. Its numbers varied in the coming years as some members resigned and more were appointed. Councilors often belonged to the social elite and included chief justices, merchants, and military officers; most were English, Anglican, and Conservative.

Tensions sometimes existed between the Liberal-dominated House and the largely Conservative Council. Elected officials often sought to increase their political powers, while many Council members tried to block their efforts. In 1833, for example, the Council rejected a revenue bill the Assembly submitted, which would have allowed the colony to tax wine, liquor, and other luxury imports. The Council argued that because the British Government already taxed these articles, it would be inappropriate for a colony to impose further levies.

In the end, Governor Cochrane and the British Government intervened to support the bill and the colony's right to impose such a tax. The island was in desperate need of money and the bill would provide it with a much-needed source of additional revenue. The House resubmitted the bill in July and the Council approved it, although one of its members, Chief Justice R.A. Tucker, resigned as a result of the conflict.

Struggles between the House and Council continued in the coming years. Although the government passed much useful legislation – including acts relating to education, road-building projects, the establishment of a savings bank in St. John's, and the protection of illegitimate children – many important bills failed to receive enough support to become acts.

Amalgamated Assembly

Recognizing that animosity between various MHAs and Council members was impeding government business, Governor Sir John Harvey and the British Colonial Office temporarily merged the Assembly and Council under a single Amalgamated Assembly in 1842. The new Assembly was an interim measure, which operated for a period of six years.

It consisted of 25 members – 15 elected representatives and 10 officials named by the governor. In addition was a Executive Council, which functioned in a manner similar to the Canadian Government's cabinet; the governor appointed its members, which included elected and nomiated members of the Assembly, as well as various prominent private citizens, such as merchants Walter Grieve and Robert Job. The Council had a membership of seven in 1842, which expanded to 11 the following year.

The public voted eight Liberals and seven Conservatives into the Amalgamated Assembly during the 1842 general election. Governor Harvey appointed the remaining 10 officials, selecting many from the previous Legislative Council. Nominees numbered seven Conservatives and three Liberals, giving the Tories a three-seat majority in the Amalgamated Assembly. Harvey, however, strongly encouraged all Assembly and Executive Council members to work in the best interest of the colony and not along partisan lines. His efforts were largely successful, as the new government operated in relative harmony for the duration of its six-year term.

When the Assembly dissolved in 1848, the British government replaced it with the previous bicameral system, consisting of a 15-member House of Assembly and a Legislative Council. The 1848 and 1852 general elections each returned nine Liberals and six Conservatives to the assembly. During this period, the Liberals fought to establish responsible government in Newfoundland, which would make the Legislative Council responsible to the House of Assembly instead of to the crown. They were successful in 1854, when Britain agreed to grant the colony responsible government; the new system came into effect in 1855 and ended the 23-year period of representative government.