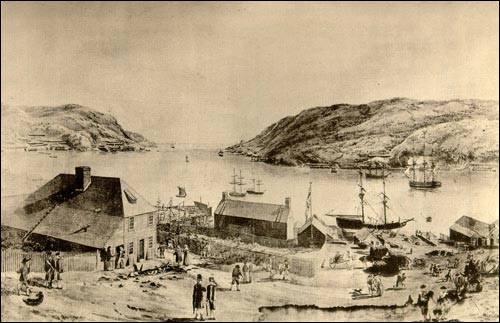

Government, 1730-1815

Until recently, government in Newfoundland during the century after 1730 has been misunderstood. Nineteenth-century commentators portrayed this era as marked principally by conflict between fishing admirals and civil magistrates. It represented a chapter of our past best left forgotten. Passed down from reformers like Patrick Morris, the picture of ignorant fishing admirals and authoritarian naval governors remains with us to the present day. We tend to see justice in the pre-modern period as a hopelessly confused mishmash of laws and traditions.

Government Stability

Nevertheless, government between 1730 and 1815 was remarkable for its relative stability and effectiveness. The primary legal resources consisted of the naval governor (appointed by annual commission from the British government), his junior officers (who acted as surrogates, the magistrates in each district (most importantly the justices of the peace, and the fish merchants who dominated St. John's and the outports. Although the fishing admirals had sharply contested the authority of the governor and magistrates as late as the 1740s, by the 1760s they were no longer an independent force. In the second half of the 18th century the fishing admirals were absorbed into the island's government, and often assisted local justices of the peace.

Dual Authority

As in the 17th century, government in Newfoundland after 1730 had a form of dual authority, but it was a cooperative system of naval and civil officials. By the mid-1760s the island was divided into nine districts, administered by civil magistrates, and five maritime zones, governed by naval surrogates. At the lower level, justices of the peace took depositions, held petty sessions, and organized quarter sessions. Each year the governor appointed several naval commanders to act as surrogate judges, ordered to the various bays to settle disputes and to preside over autumn quarter sessions - termed a surrogate court - usually with the local justices of the peace. Governors worked to consolidate authority, but the overlapping jurisdictions remained localized and varied considerably according to regional customs and accessible resources. Whereas St. John's and Harbour Grace maintained regular appointments of justices and coroners, commissions of the peace for other areas, such as Trinity and Bonavista, periodically lapsed for several years.

Four Courts

The most important theme in the history of law and government in this period is the process by which the island's institutions adapted to local conditions. Aside from the court of oyer and terminer, which heard serious criminal offences, four courts dominated the administration of justice in Newfoundland: the governor's court in St. John's; the surrogate courts; the sessions held by justices of the peace; and the vice-admiralty court at St. John's.

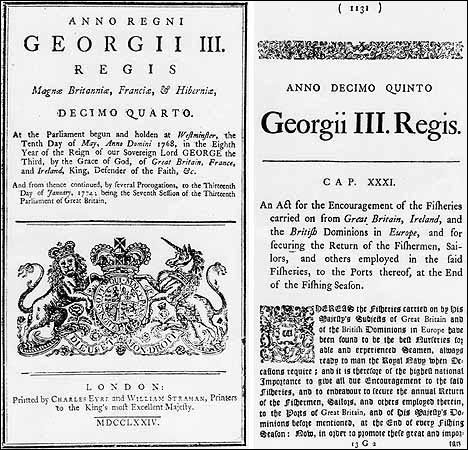

Each of these institutions evolved beyond its formal jurisdiction. For example, while naval officers were authorized by parliamentary statute (King William's Act of 1699) only to act as appeal judges, in practice they judged a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. The surrogate courts were based on customary law, in other words, the practices which came over the years to be recognized as legitimate authority. Such customary practices were, in fact, an accepted part of the English common law tradition. When the British parliament passed a new act for the Newfoundland fishery in 1775, known as Palliser's Act, it merely codified existing customary laws.

Major Crisis

From 1787 to 1791 the legal system in Newfoundland experienced a major crisis. An appeal heard in England against a decision by a surrogate judge threw the island's judiciary into confusion. Cases piled up by the hundreds while authorities tried to decide how best to reform the courts. In 1789 the crisis deepened further when a shipload of Irish convicts was landed at Bay Bulls and Petty Harbour. Admiral Mark Milbanke, who had just been appointed governor, had to overhaul the judiciary at the same time as he dealt with the dangers posed by the convicts. Faced with these problems, the British government conducted an investigation into law and government in Newfoundland. An act passed in 1791 gave Newfoundland a new constitution and its first chief justice, and the following year another act established a supreme court.

Yet for the next 30 years the government of Newfoundland functioned largely as it had before 1787. The governor, assisted by a secretary, presided in St. John's, assisted locally by surrogates, justices of the peace, and merchants. In official terms, Newfoundland remained a seasonal fishing station with neither colonial status nor a local legislature. It is important to note that this type of government was not relatively backward, it was relatively different, and certainly just as effective as that in other British colonies. However, during the Napoleonic Wars the island experienced massive social and economic change, and after 1815 a local reform movement emerged to pressure the British government to grant Newfoundland its own elected assembly.

Naval Government

Generally speaking, the period of 1730 to 1815 represents the age of naval government in Newfoundland. The governor was also the commodore of the naval squadron sent each summer to protect the fishing fleet; until 1792 all of the surrogate judges were naval commanders; and the island was seen as a "nursery" for British sailors.

Beginnings of Civil Government

This era also marks the beginnings of civil government in Newfoundland, the establishment of local magistrates, and the development of customary law. Added to this system of government were the powerful fish merchants, who became involved whenever they perceived their property to be threatened. Without an independent press or popularly elected assembly to question their decisions, authorities in Newfoundland responded to problems as they saw fit. It may not have been a very fair or just system, especially when compared to modern standards, but it operated effectively for nearly a century.