Impacts of the Collapse of Responsible Government

The replacement of responsible government with the non-elected Commission of Government in 1934 had far-reaching consequences for Newfoundland and Labrador society, economy, and politics. The Commission remained in power for 15 years, during which time the Second World War brought much economic prosperity to the country and helped integrate it into North American society. Although contact with Canada and the United States increased dramatically during the 1940s and helped shape Newfoundland and Labrador's future, it was largely controlled by the commissioners.

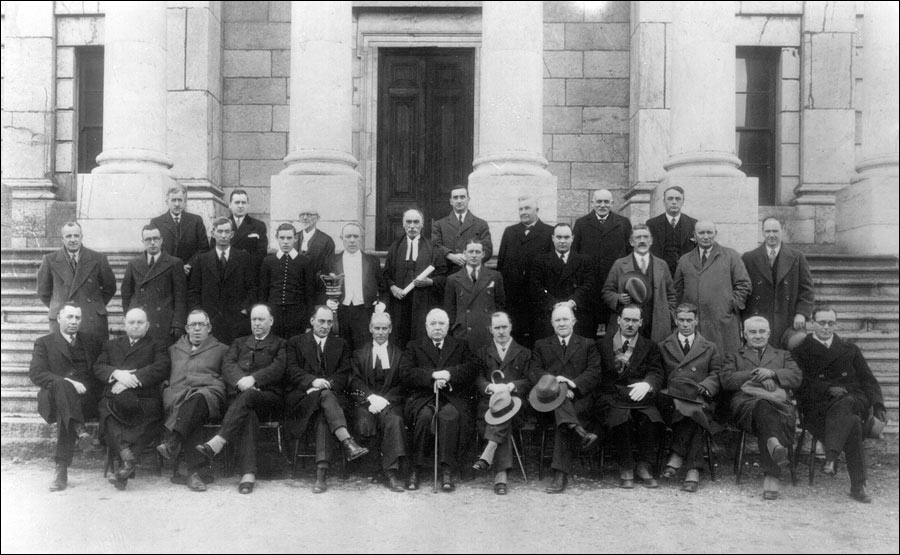

Seated in the first row (left to right): Kenneth M. Brown; William C. Winsor; William J. Walsh; Sir John C. Puddester; F. Gordon Bradley; James A. Winter; Frederick C. Alderdice; Sir Edward Emerson; John G. Stone; William J. Browne; Harry A. Winter; Samuel J. Foote; and Harold Mitchell.

Standing in the second row (left to right): Ernest Gear; Phillip J. Lewis, William A. Abbott; page; Sergeant-at-Arms; Patrick K. Devine (Assistant Clerk); Michael A. Shea; Herman W. Quinton; Charles J. Furey; Dr. Harris M. Mosdell; and Gerald G. Byrne.

Standing in the third row (left to right): George Whiteley; Patrick F. Halley; Henry Y. Mott (Clerk); Henry Earle; Norman Gray; Joseph Moore; and Roland G. Starkes.

It was not until 1946 that the people returned to the polls to elect members of the National Convention. By then, almost half of all eligible voters had never cast a ballot before, having been too young to participate in the previous election 14 years earlier. Voters again went to the polls in 1948 to decide between a return to responsible government and confederation with Canada.

End of Responsible Government

The suspension of responsible government in 1934 followed years of economic hardship and political chaos in Newfoundland and Labrador. The international market for saltfish and the country's other exports decreased dramatically during the Great Depression, causing public revenues to fall. At the same time, unemployment sharply rose and forced the government to spend what little money it had on relief. Public discontent climaxed when finance minister Peter Cashin accused Prime Minister Sir Richard Squires of misusing public funds in the spring of 1932. Violent riots and protests occurred outside the Colonial Building and an ensuing election forced Squires from office.

By the end of that year, it seemed likely the country would not be able to make interest payments on its $100-million public debt. Britain agreed to help, but in return wanted greater political control over the country to protect its investment. It requested a commission of inquiry investigate the country's political and financial affairs and appointed Lord Amulree, formerly Sir William Mackenzie, as its chair.

The committee's report, published in October 1933, ignored the effects of the depression and mistakenly blamed the country's problems on political mismanagement and corruption alone. It stated the people needed "a rest from politics for a period of years" during which time a British appointed Commission of Government should manage the country. On 16 February 1934 Newfoundland and Labrador ceased to be a self-governing nation and the commissioners were sworn in.

Initial Reaction

The change initially sparked little protest from the public. Years of economic and political uncertainty took a toll on the people and many believed party politics were inherently corrupt. The Amulree Report supported this view by neglecting to attribute any of Newfoundland and Labrador's problems to the global economic downturn. Many people hoped the commissioners would govern the country efficiently and set it on a sound financial footing. A St. John's Daily News editorial published on 4 December 1933 stated "In all ranks of life, and especially among diligent and hard-working citizens … the most frequently heard expression is one of thankfulness that party politics has been thrown into the discard for a period."

Nonetheless, the Amulree Report sparked public dialogue about the nature of Newfoundland and Labrador society. Some felt the country's economic and political problems reflected shortcomings in the character of its people, who, according to the report, "exhibit a child-like simplicity when confronted with matters outside their own immediate horizon." Amulree argued the people were easily exploited by politicians and not equipped to sustain a modern parliamentary democracy.

In the years following the report, some local writers feared the rest of the world perceived Newfoundland and Labrador citizens as naïve, old-fashioned, or corrupt. In his 1937 essay "Newfoundland To-day," JR Smallwood wrote of the "backwardness" of the country's people and argued the traditional way of life had "helped to unfit us for creative and constructive effort." In 1934, St. John's educator J.L. Paton wrote in the May-June issue of International Affairs that "wherever I go I am regarded with a sort of suspicion, as though, coming from Newfoundland, I must be a 'grafter.'"

Growing Discontent

The public's initial confidence in the Commission of Government gave way to disappointment and discontentedness by the end of 1935. Unemployment was still widespread and there was no perceptible increase in the country's standard of living. Worse, the commissioners operated in relative secrecy, leaving the public with virtually no say in the administration of its own country. Protestors demonstrated outside the Colonial Building in May 1935 to demand work or food, but with little result. By 1939, more people were on government relief than when the Commission assumed power in 1934.

The Second World War, however, brought much economic prosperity to Newfoundland and Labrador as the construction of Allied military bases at St. John's, Botwood, Goose Bay, and elsewhere created thousands of jobs for local workers and helped boost government revenues. The influx of American and Canadian military personnel also helped integrate the Newfoundland and Labrador people into North American society. Sudden access to more varied groceries, better health care facilities, and North American radio stations helped change local values and attitudes and increase the standard of living.

By 1945, the country regained its financial independence and was ready to assume a new form of government. The Great Depression and Second World War, however, had altered Newfoundland and Labrador society. Many people were accustomed to the North American quality of life and did not want to relive the difficult times of the 1920s and 30s. Some still associated responsible government with corruption and feared a return to independence would also mean a return to poverty and unemployment.

Confederation or Responsible Government

It was in this atmosphere that the country had to decide between responsible government and confederation with Canada. Advocates of the latter believed Canada's federally financed social programs could provide the people with greater security than anything responsible government would offer, while supporters of an independent Newfoundland and Labrador felt self-government would allow the people to determine their own fate according to their own interests. Others suggested the country should resume responsible government and then negotiate terms of union with Canada as an independent nation and therefore on equal grounds.

Some people also worried the public had grown detached from politics since losing the right to vote and argued the Commission had done nothing to ready the population for a return to independence. One of the most vocal critics was anti-confederate reporter Albert Perlin, who wrote in the 8 May 1946 edition of the Daily News that "Today we have reached an ebb in political consciousness. For want of some focal point of interest in affairs during the past twelve years, our political senses have been dulled and five years of prosperity have aggravated this condition by giving us an undue complacency."

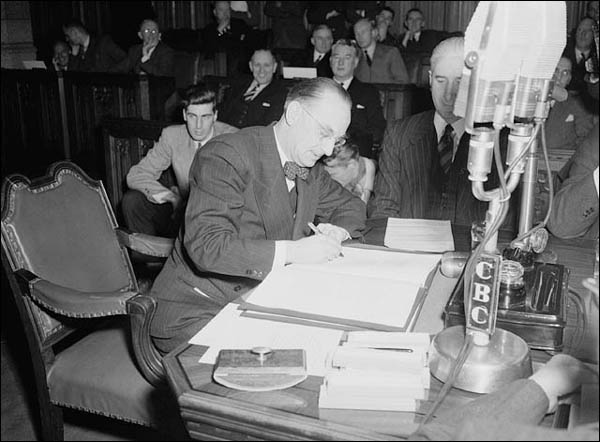

In the end, Confederation won by a margin of 6,989 votes out of 149,667 cast and a provincial government replaced the Commission. The result sparked much debate and controversy, some of which continues today as members of the press, public, and academic community question how much the depression, Second World War, and loss of responsible government impacted Newfoundland and Labrador society and its decision to join Canada.