Innu Organizations and Land Claims

The Innu people of Labrador formally organized under the Naskapi Montagnais Innu Association (NMIA) in 1976 to better protect their rights, lands, and way of life against industrialization and other outside forces. The NMIA changed its name to the Innu Nation in 1990 and today functions as the governing body of the Labrador Innu. The group won recognition for its members as status Indians under Canada's Indian Act in 2002 and is currently involved in land claim and self-governance negotiations with the federal and provincial governments.

In addition to the Innu Nation, residents at both Sheshatshiu and Natuashish elect Band Councils to represent their needs and concerns. The chiefs of both councils sit on the Innu Nation's board of directors and the three groups often work in cooperation with one another. Although Sheshatshiu and Natuashish are home to most of the province's Innu people, some also live at Labrador City, Wabush, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, St. John's, and elsewhere.

Early Government Involvement

The Newfoundland and Labrador government had little direct contact with the Innu people before the mid-20th century. Unlike many Canadian regions, trade between Indigenous peoples and European settlers at Labrador did not evolve to the extent that it required formal legislation or significant government involvement. Moreover, Labrador was far removed from the centre of political activity at St. John's and it would have been costly and difficult for politicians to provide services to the territory's small scattered population.

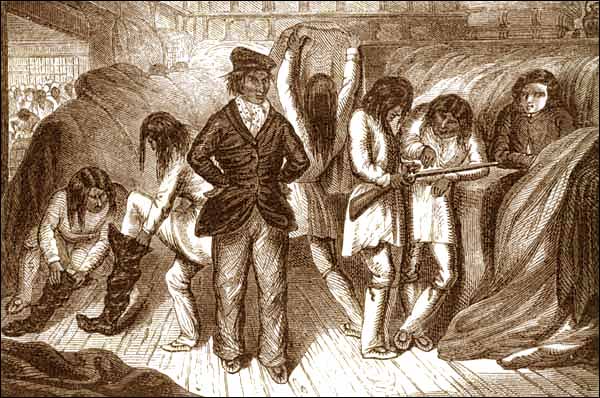

Instead, government officials delegated the day-to-day administration of Labrador affairs to religious groups and commercial trading companies in the area, the most prominent of which were Christian missionaries and the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Roman Catholic priests at Davis Inlet, for example, distributed food, clothing, and other forms of social assistance to the Innu people by the 1930s. In 1935, the Commission of Government created the Newfoundland Ranger Force to police isolated and rural areas, including Labrador. Alongside enforcing game and other laws, rangers distributed government relief payments and acted as a link between local residents and government officials.

Confederation

At the time of Confederation in 1949, the Newfoundland and Labrador government did not have any special agencies in place to deal with Indigenous affairs and it had not developed a system of reserves or land claim treaties with the Innu, Mi'kmaq, Inuit, and Southern Inuit people. In Canada, the Indian Act made the federal government financially responsible for the delivery of health, education, and other social services to much of its Indigenous population.

When Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada, the two governments did not extend the Act to the new province's Indigenous peoples. Government officials argued that doing so would disenfranchise Newfoundland and Labrador's Indigenous residents, who, unlike most status Indians in Canada, had the right to vote. Some academics today question that argument and instead suggest the large costs of providing services to Labrador's remote and dispersed population deterred Ottawa from including its Indigenous peoples under the Indian Act.

In lieu of extending the Indian Act, federal officials agreed to pay money to the Newfoundland and Labrador government for the delivery of education, health, and other services in Indigenous communities. The province used some of these funds to build houses and schools at Sheshatshiu and Utshimassit (Davis Inlet) in the 1960s. It also made it mandatory for Innu children to attend school and threatened to stop welfare and family allowance payments to families whose children did not attend class.

As a result, many Innu families had to live in the communities for most of the year, despite their concerns that doing so would threaten their migratory way of life and connection to the land. Innu parents also felt the school curriculum taught their children more about white North American society than their own and worried younger generations were being alienated from their cultural traditions.

Compounding these concerns were a string of post-Confederation forestry, mining, and other industrial developments that occurred on Innu land, but without Innu permission. Most dramatic among these was the Upper Churchill Falls hydroelectric project, which flooded thousands of kilometers of land in Labrador, including valuable caribou habitat and Innu burial grounds. Although the Innu people used and depended on much of this area for centuries, the provincial government did not consult them before damming the Churchill River.

Innu Political Organizations

Recognizing a need to protect their land, resources, and culture against future threats, the Innu people joined the province's Mi'kmaq and Inuit people in 1973 to form the Native Association of Newfoundland and Labrador (NANL). The Innu people broke away from NANL three years later to form the Naskapi Montagnais Innu Association, which changed its name to the Innu Nation in 1990.

The Innu Nation today represents about 2,200 Innu people, who elect a president and board of directors to oversee the group's political, business, and other affairs. The Innu Nation's mandate is to provide a unified political voice to protect the Innu people's interests against outside threats, as well as to pursue land claim negotiations and help deliver education, health-care, and other social services to its membership. In the past, the group has protested low-level military flight training over Innu lands and various industrial projects that affected Innu resources, including the Lower Churchill Falls hydroelectric project, clear-cutting operations, construction of the trans-Labrador highway, and the Voisey's Bay nickel mine.

The Innu Nation has made strides in a number of areas as a result of its efforts. Both the provincial government and Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro have agreed to include the Innu Nation in the development of the Lower Churchill Falls; the three parties are also negotiating a deal that could give the Innu Nation a minority ownership of the hydroelectric project. In addition, Canadian mining company Inco Ltd. is paying the Innu Nation royalties for its work at Voisey's Bay. As of 2007, the Innu Nation has received $4 million in mining revenues. The province also developed a Forest Process Agreement with the Innu Nation in 2001 to allow for full Innu participation in forest planning within central Labrador.

Alongside the Innu Nation, residents at Sheshatshiu and Natuashish elect Band Councils to represent their needs. As of 2008, the Sheshatshiu Band Council consists of one chief and six councilors, while the Mushuau Band Council at Natuashish consists of one chief and four councilors. Both council chiefs also sit on the Innu Nation's board of directors.

In 2002, the Innu Nation and two Band Councils succeeded in having the federal government register the Labrador Innu as status Indians, giving them access to various federal programs and services for First Nations people in Canada. The government also recognized the communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu as reserve lands in 2003 and 2006, respectively.

Land Claims

Indigenous groups file land claims with the federal and provincial governments to obtain rights to land and resources they and their ancestors used in the past and did not hand over to European colonists or subsequent governments. Land claim negotiations often take years or decades to complete and must pass through a series of steps, including a Framework Agreement, an Agreement-in-Principle, a Final Agreement, and implementation.

The Innu Nation filed its first claim with the federal government in November 1977 for land in central Labrador. Government officials decided there was not enough information backing up the claim and gave the Innu Nation money to conduct further research. The group filed another land claim in October 1990, which led to the signing of a Framework Agreement in 1996.

As of 2008, negotiations towards an Agreement-in-Principle are ongoing between the Innu Nation and the provincial and federal governments. As part of its land claim talks, the Innu Nation also began negotiating self-government arrangements with the provincial and federal governments in 2006.