The Boyd's Cove Beothuk Site

The Boyd's Cove site lies in eastern Notre Dame Bay on the island of Newfoundland's northeast coast. It is situated at the bottom of a bay and is protected by a maze of islands that shelter it from waves and winds. The site was found in 1981 during a survey to locate Beothuk sites, a search that was begun because existing historical records could not answer a number of important questions about the Beothuk.

Searching for Information

Shanawdithit, the last known Beothuk, died in St. John's in 1829, and since her death scholars and the public alike had puzzled over the reasons for their tragic extinction. By the end of the 1970s, archaeologists such as Raymond LeBlanc (1972) James Tuck (1976), and historians such as Frederick Rowe (1977) and Leslie Upton (1977), had concluded that Beothuk extinction was not the result of a genocidal campaign by white settlers, but rather the result of European disease and starvation--the latter resulting from an expanding European settler population that denied the Beothuk access to the vital resources of the sea. Many other writers had also commented on the fact that the Beothuk appear to have generally avoided contact with Europeans, and Upton had noted that there was virtually no fur trade between European traders and the Beothuk. This was indeed unusual, for elsewhere in North America, Native peoples sought out Europeans to trade furs for blankets, kettles, knives, hatchets, and the like. The first question, then, was why the Beothuk avoided Europeans.

There was also a gap in the historical record. After John Guy met with Beothuk in 1612, there were very few references to them until the last half of the 18th century. In part this was because of their strategy of refusing contact. In addition to the absence of fur traders in Newfoundland, there were also no missionaries and no Indian agents attempting to make contact with them. Thus, the search was aimed at finding Beothuk sites occupied during the period from roughly 1612 to 1750.

Because of the scarcity of record-keeping Europeans in contact with the Beothuk, we know less about their life than we do about peoples such as the Huron or the Mi'kmaq. French missionaries lived with these peoples and had recorded a great deal of information about them in collections such as The Jesuit Relations. European fur traders also dealt with them, and, in the case of the Mi'kmaq, agents of the French crown had sought to win their assistance in France's wars with England. As a result, we know something about how the Huron and Mi'kmaq were governed, the role of women in their societies, their religious beliefs, and so forth. While archaeology might not be able to provide information of the kind found in The Jesuit Relations, it has the potential to produce the sort of evidence that is sometimes lacking in the historical record.

The attempts to answer these questions led to a focus on Notre Dame Bay. There were a number of historical references to the Beothuk in this region, especially in the last half of the 18th and the early part of the 19th century. Previous archaeological surveys and finds by amateurs indicated that it was likely that the Beothuk had lived here even earlier. This was not surprising; historically, eastern Notre Dame Bay has been known for its seals, fish, and sea birds, and its hinterland, drained by the Exploits River, supported large caribou herds.

Boyd's Cove Historical Site

With this in mind, topographical maps and aerial photographs were examined, and local residents were interviewed. Nothing would take the place of actually visiting the many coves, bays, islands, and beaches of the area, however, and an extensive survey by boat and foot was begun in June of 1981. Ideal locations would have a good beach on which to draw up canoes, a nearby source of fresh water, protection from winds and waves, and a close proximity to resources. Ultimately the archaeologists found 16 Indigenous sites, ranging from the Maritime Archaic Indian era through the Palaeo-Eskimo period, down to the Recent Indian (which includes the Beothuk) occupation. Fortunately, two of the sites were historic Beothuk. Boyd's Cove, the larger of the two, is 3000 sq. m and is located on top of a 6 m glacial moraine, a deposit of coarse sand, gravel and boulders left behind by the glaciers which once covered Newfoundland. The porous composition of the moraine allows rain water to drain through it quickly; thus the pit houses of the Beothuk, which were dug into the ground, would be dry soon after a rain. The site has a narrow beach, as well as a stream that supplied fresh water and was (and still is) the source of huge numbers of American smelt that spawn there every year in early May. The hundreds of tiny smelt bones found at Boyd's Cove, indicate that its inhabitants ate them regularly. Such tiny bones are usually dissolved in Newfoundland's acid soils, but because the Boyd's Cove people also ate large quantities of clams and mussels, the discarded shells buffered the soil and made it much less damaging. This meant that the bones of the animals found at Boyd's Cove were largely preserved--an extremely unusual situation in Newfoundland.

Beothuk Diet

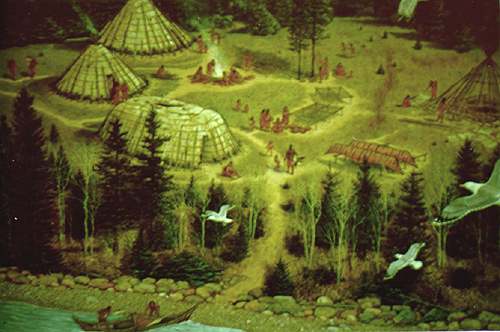

The Beothuk who lived here ate a rich and varied diet. Bones from harp seals, harbour seals, polar bears, beaver, caribou, sculpin, flounder, geese, cormorants, and many other animals suggested that good hunting and fishing were two of the reasons why the site was occupied. The Beothuk tended to discard these food remains inside abandoned house pits, the most striking feature of the site. Ultimately, eleven house pits were located at Boyd's Cove, nine roughly circular, or multi-sided, and two oval in shape. These were the remains of pit houses that were, on average, about 6 m in diameter and were built by digging a shallow depression in the ground, erecting a wigwam within that depression, covering it with bark, and then piling up the excavated earth around the edges of the wigwam. The result was a warm, water-tight structure that could be lived in (with regular repair) for a number of years.

Beothuk Housing

Based on the location of these houses, the patterning of the refuse thrown into them, and the types of artifacts found, it appears that--with one exception--three or four houses were inhabited at a time, probably by a band of perhaps 30-35 people, certainly no more than 50. Three of the multi-sided houses and one (House 4) of the oval type were excavated. House 4 measured about 9.5 metres x 4.5 mestres and, while it was constructed in much the same manner as the others, it had a large hearth, or fireplace, running down its centre. This hearth was filled with charcoal, ash, burnt bone and what might be called “bone mash”, bone that had been ground to a powder. In fact, the evidence from this house and hearth pointed to what was likely an important Beothuk religious practice. Even today, in Labrador, the Innu hold a feast called a mokoshan, to honour the spirit of the caribou. In a mokoshan, caribou long bones are ground up and boiled in a kettle, and when the grease rises to the top of the water, it is pressed into cakes and eaten. All of the bones are carefully put in the fire. In earlier times, such a feast was carried out on either side of a long hearth in an oval structure called a shaputuan. Shaputuans often were built with two entrances as was the case with House 4; in fact, House 4 is almost exactly what one would expect to find after a mokoshan feast had been held within a shaputuan. House 4 also provided one more clue about Beothuk religious beliefs. It produced a carving of what appears to be a stylized bear--perhaps an amulet worn to honour the spirit of the bear, to insure good hunting, or perhaps to provide protection from bears.

Reasons for Avoiding the Fur Trade

Boyd's Cove also answered some significant economic questions. Most important was a clue as to why the Beothuk did not engage in a fur trade. The interiors of four houses and their environs produced some 1,157 nails, the majority of which had been worked by the Beothuk. Some 67 iron projectile point (most made from nails) had been manufactured by the site's occupants. Nails had also been modified into what are believed to be scrapers to remove fat from hides; fish hooks had been straightened out and made into awls; lead had been fashioned into ornaments, and so on. Clearly, the Boyd's Cove Beothuk were taking the debris from an early modern European fishery and refashioning it for their own purposes.

All over North America, Native people had traded furs for metal implements for cutting, piercing, and scraping. In Newfoundland, however, the Beothuk could acquire such objects by visiting European fishing premises in the fall, after the fishermen left to go back to Europe, and picking up discarded or lost nails, fish hooks and iron scraps. There were real advantages to this strategy. A fur trade, while it could yield a wide variety of European goods for Native people, also entailed considerable cost. Native hunters and fishers had to time their movements precisely to take advantage of the availability of various animal species.

In Newfoundland, for example, this might mean travelling to the Exploits River in October and November to intercept the caribou as they crossed the river on their annual fall migration, going out to the headlands and outer islands in late winter/early spring for the harp seal hunt, then to bird nesting sites on the coast in May and June for eggs, and clustering along salmon rivers in the summer. A fur trade would mean spending the colder months hunting small fur-bearing animals, most of which (aside from beavers) provided little or no edible meat.

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, a fur trade would also mean congregating in sheltered harbours in late spring to await European fishermen. By the early 17th century, for example, peoples such as the Mi'kmaq and the Montagnais (Innu) of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, who had been trading with migratory European fishermen/fur traders for a century or more, had become dependent upon foods such as flour, salt meat and dried peasto make up for the loss of food that resulted from their hunting of fur-bearing animals rather than food species. European food was less nutritious than traditional fare and contributed to the growing problem of Native ill health. Trading with Europeans could also be more immediately dangerous for Indigenous people. Occasionally, there were violent conflicts between the two groups, and traders all too frequently brought alcohol and European disease with them. Because the Beothuk could acquire desirable metal objects without running these sorts of risks, it is not difficult to see why they preferred not to trade.

A single canoe trip to a seasonally-abandoned European fishing station might produce a boat-load of nails--much easier than trapping fur-bearers, curing their skins, and seeking out European traders. Picking up lost and discarded metal objects was probably often easier than acquiring stone--the raw material for precontact Beothuk. Stone quarries were not always conveniently located on the coast, and the stone had to be chiselled out, carried off in the form of heavy blanks, and later worked into tools. On balance, the Beothuk practice of acquiring metal objects from fishing stations was a very rational and efficient strategy. This is probably another reason why Boyd's Cove was a good place to live--it lay between a French fishery to the northwest and an English fishery to the southeast. Artifactual evidence from the site suggests that it was occupied during the period ca. 1650 to 1720, and during this time Boyd's Cove would have been in a protected niche between two European fisheries. Indeed, small shards of French and English pottery suggest that the Boyd's Cove Beothuk were visiting the abandoned shorestations of both nations for their supplies of iron.

Trade Beads

Although there is strong evidence that the Boyd's Cove Beothuk were not trading with Europeans, the site did yield 577 tiny beads, all of which were either blue or white. Trade beads are a common artifact on historic Native sites, but beads are usually found in the thousands and are generally accompanied by other trade goods such as hatchets, bells, rings, mirrors, etc. These beads, however, hint at peaceful contact with some group, probably the Montagnais, or Innu as they prefer to be known today. In the early 18th century, Innu trappers from Labrador occasionally visited the island of Newfoundland, and there is some evidence that they contacted the Beothuk. It is quite possible that the Boyd's Cove beads were traded or given to the Boyd's Cove Beothuk by Innu from Labrador. By the 1720s a European salmon fisherman had set up his nets in Dog Bay, only 6 k from Boyd's Cove, and by the 1730s, the community of Twillingate had been established 30 k from the site. The presence of Europeans, so close to the highly visible wigwams of Boyd's Cove, would have persuaded its inhabitants to move--perhaps westward to a locale less well-known to the white strangers. By the middle of the 18th century it was increasingly difficult for the Beothuk to hunt and fish along the coastlines, and they were forced to spend more and more time in the interior living on caribou and beaver. Without the resources of the coast, however, it has always been impossible for hunters and fishers to live in Newfoundland, and the last known Beothuk died in 1829. We should remember, however, that for the Beothuk of Boyd's Cove, this was far in the future, and the evidence from the site suggests that they were living well, perhaps better than at any time in their long history.