Migratory Fishery and Settlement Patterns

Thousands of European fishers annually visited Newfoundland and Labrador from the 16th through the 18th centuries to participate in the transatlantic migratory cod fishery. Although the vast majority of workers returned home during the fall, some chose to remain on the island year round to safeguard fishing gear and for a variety of other reasons. Most settled in coastal areas that were relatively sheltered, near good fishing grounds, and allowed for easy access to a supply of wood.

By the time the migratory fishery gave way to a resident one in the early 1800s, a pattern of settlement had emerged that helped shape population dispersal for years to come. Often, what began as rough seasonal fishing camps in the 16th century gave way to permanent settlements by the 19th century, while larger mercantile communities at St. John's, Trinity, Placentia, and elsewhere developed into more densely populated commercial centres. For most of the 1800s, settlements were almost exclusively located near the shoreline, with most situated on the Avalon Peninsula and along Newfoundland's southeast and northeast coasts.

Early Settlers and Protected Fishing Equipment

Beginning in the early 16th century, significant numbers of European fishers travelled to Newfoundland and Labrador each spring to catch cod. Before the fishing season began, workers spent about a month on shore building cabins, cookrooms, fishing stages, flakes, small open boats, and other structures vital to the industry. From June through August, workers sailed to inshore fishing grounds each morning and spent evenings and nights at makeshift camps. Most returned to Europe in the fall, leaving their camps abandoned until the following spring.

The fishers' departure made their cabins, gear, and fishing grounds vulnerable to theft, vandalism, or destruction by interlopers. It was not uncommon for fishers to steal boats or destroy flakes belonging to crews from rival nations and regions. Further, the fishery was a common property resource, making it impossible for workers to secure fishing grounds from competing crews during their absence. Whichever fleet arrived at a location earliest had claim to it for the remainder of the fishing season.

The Beothuk — Newfoundland's only permanent Aboriginal residents — posed another problem for migratory fishers. Once crews departed for Europe, the Beothuk frequently scavenged abandoned fishing stations for nails, hooks, and other metal items they used to make arrowheads for harpoons and spears. A single boat could yield about 1,200 nails, while a fishing stage likely held thousands. The quickest and easiest way for the Beothuk to obtain nails was to burn the equipment, which destroyed it beyond repair. When European fishers returned in the spring, they had to spend much time and energy rebuilding campsites and fishing gear. A similar relationship existed between the Inuit people and migratory fishers at Labrador until the Moravian Church established a string of mission stations there in the late 18th century. Mission workers assumed all trade operations with the Inuit and forbade Europeans from entering mission grounds.

Some fishers overwintered at Newfoundland and Labrador to safeguard equipment and secure access to prime fishing grounds. Driving the movement toward year-round residency were planters – fishing masters who owned boats and stages that required protection during the winter. While many planters chose to remain on the island with their servants, and sometimes with their families, others hired workers to stay behind and guard gear in their stead.

Also present were proprietary colonists – including Sir David Kirke at Ferryland — who settled on the island during the 17th century. These were large-scale planters whose operations were similar in size and nature to those of the West Country merchants — they owned their own fleets, hired crews, and outfitted vessels for the fishery. Although the British government did not initially object to the colonies, it tried to curb tensions between major planters and both migratory fishers and small-scale planters by passing legislation in the 1630s forbidding settlement within six miles of the shore and prohibiting the occupation of fishing rooms until European fishing crews arrived each summer.

Although migratory fishers' and colonists' activities often overlapped and they dealt with each other, frictions were common between the two groups. Migratory crews felt Kirke and others monopolized the best fishing rooms and locations, while West Country merchants feared permanent settlement of Newfoundland and Labrador would threaten their control of the fishery. Although many 17th-century proprietary colonies ended in economic failure because profits from the fishery were rarely enough to offset the costs of settlement, they did help establish the infrastructure of a resident fishery.

During the winter of 1700, about 4,000 people inhabited Newfoundland's English Shore, which stretched along the island's east coast from Bonavista to Trepassey. Of these residents, approximately 300 were planters; also present were a few independent traders and representatives of West Country merchant firms. It was the planters' servants, however, who made up the bulk of Newfoundland's overwintering population. In addition, approximately 1,000 other people lived in French settlements on Newfoundland's southeast coast by the 1680s. This changed after the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, when France ceded its territory in Newfoundland and Labrador to Britain.

Coastal Settlements

An increasing number of Newfoundland's harbours and coves supported small-scale, year-round communities throughout the 18th century. Most inhabitants, however, did not remain on the island for long and often returned home after a single year of residency. To compensate, planters hired new servants from England and Ireland to protect their fishing stations during the winter. As a result, many coastal areas were consistently populated, but usually by small numbers of short-term residents. Some European fishers also took up year-round residence in Labrador's coastal areas, but in much smaller numbers than they did on the island.

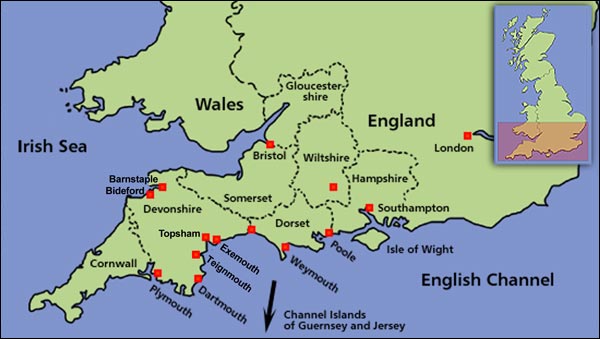

The pattern of habitation that emerged during the migratory fishery set the groundwork for future settlement by permanent residents. Because planters were primarily interested in Newfoundland and Labrador's fish resources, settlement areas were almost exclusively confined to coastal areas near productive fishing grounds and within relatively close travelling distance to Britain. Headlands and peninsulas on the east coast were favoured locations for fishing, and therefore for settlement.

Much activity occurred on the Avalon Peninsula and in Trinity, Bonavista, and Placentia Bays. These areas were near productive fishing grounds and international trade routes, were closer to Europe than any other point on Newfoundland and Labrador, and offered many sheltered harbours and coves. When the migratory fishery gave way to a resident one in the 19th century, these areas were among the most densely populated on the island – largely due to their early prominence as productive fishing stations.

St. John's quickly emerged as one of the busiest and most important harbours of the migratory fishery. By the end of the 17th century, it served as a major port of call for international trading vessels bringing supplies to fishers and taking away cargoes of cod. Britain also established a military garrison there by the start of the 18th century to protect its interest in the fishery. St. John's steadily grew in importance as a communications and administration centre in the coming decades, and ultimately developed into the colony's capital city.

West Country Merchants

European fish merchants also had much influence over migration and settlement patterns in Newfoundland and Labrador. As early as the 17th century, British merchants supported small-scale colonization of Newfoundland and Labrador as a means of reducing the risks of the migratory fishery and increasing the length of the fishing season. Colonization attempts took place at such places as Cupids, Renews, and Ferryland, but usually ended in failure because the cod fishery alone could not support year-round habitation.

During the 1700s, most merchants involved with the migratory fishery were situated on England's southwest coast in the West Country. Merchant firms from various West Country regions tended to trade with specific areas in coastal Newfoundland and Labrador – those in South Devon, for example, traded mainly to the St. John's and Conception Bay areas. As a result, workers in the employ of various firms migrated to specific areas of the island. Because merchants recruited servants from England and Ireland, workers from both of these areas arrived at Newfoundland and Labrador during the 1700s.

As the 18th century progressed, many West Country merchants increasingly relied on year-round residents for cod, oil, furs and other goods, while at the same time selling supplies to people in Newfoundland and Labrador. These trade negotiations encouraged year-round settlement by promoting winter work in the sealing and furring industries, and by providing settlers with food, clothing, and other provisions not available locally. By the end of the 1700s, merchant firms had established bases at Trinity, Bonavista, Placentia, Brigus, and elsewhere on the island. These communities developed into regional centres of communication and commerce, linking nearby villages and facilitating permanent settlement.

Although the migratory fishery was not the sole factor leading to the permanent settlement of Newfoundland and Labrador by European migrants — wars, socioeconomic conditions overseas, and the emergence of local winter industries were also important factors — it did do much to lay the foundation for future settlement patterns within the colony, many of which may still be seen today.