Garrison Life in the 18th Century

Page 3

Inadequate Pay and Food Allowances

Soldiers' pay was wholly inadequate, given the cost of living. Men were paid 18½ pence every Monday. Those who were married received an additional food allowance for their wives and children. The wife received half a ration, the children received a quarter ration each, a normal ration being 1 lb. of bread and 3/4 lb. of meat per day.

These allowances were so inadequate that the soldiers were encouraged to grow vegetables. The land around Fort William and later Fort Townshend was turned over to garden plots. Both officers and soldiers farmed this land, and by 1831 Fort William was said to resemble a farm rather than a military post. The parapet of its harbour-side battery was overrun by marauding hens and sheep. Thus, one important consequence of the military presence was the way in which it encouraged subsistence agriculture. Men with recognition for good conduct were also entitled to fishing passes, and archaeological evidence suggests that fish was a very important part of the diet.

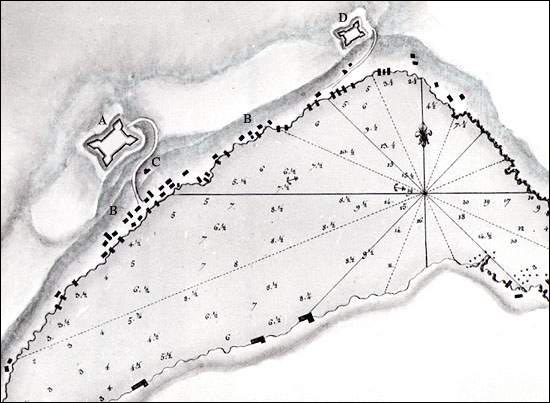

Legend

A. Fort Townshend

B. The Town

C. The Church

D. Fort William

Poverty and Destitution

Nevertheless, the soldier stationed in Newfoundland, especially if he was married, frequently faced poverty, even destitution. Soldiers were rarely paid in cash, but in notes. Local merchants refused to accept these at face value, charging a substantial discount. And the extremely high mark-ups on goods further eroded purchasing power. Occasionally, an officer might acquire some hard currency before leaving England or Ireland. He would sell the cash to his soldiers for a 5% to 7% premium, which became his profit. Newfoundland was practically a cash-free society, and the few coins which were in circulation came from all over the North Atlantic trading world. To be paid in this "ready currency", a soldier had to accept the cost of the cash premium as well as the cost of currency exchange. And always, the soldier faced discriminatory exchange rates from the local merchants. To buy a Spanish dollar (a labourer's daily wage), a soldier had to pay five shillings in scrip when the going rate charged to civilians was 4 sh/6 d.

Hard Currency in St. John's

During the American Revolution, chests of hard coin were sent out from England to pay the soldiers, in order to maintain their morale at a critical time. This practice was abandoned when the war ended, and by 1797, when England was once again at war with France, the failure to pay the troops in cash was causing such loud complaints that the governor feared a mutiny. He therefore urged the government to find a way of introducing cash. This was done, and the governor urged that the practice be maintained. Otherwise, the cash gravitated into the hands of the merchants and quickly went out of circulation because merchants tended to hoard it, or use it to pay off their overseas debts. Apparently, the appearance of hard currency caused retail prices in St. John's to fall dramatically. Bread, which had sold at 6d/loaf, now sold for only a penny or two. Thus, the presence of the garrison played an important role in pumping hard currency into the St. John's economy, and enhanced that town's growing economic importance.