The French Treaty Shore

The French Treaty Shore came into existence with the ratification of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). This provided that the French could fish in season on the Newfoundland coast between Cape Bonavista and Point Riche - an area that had been frequented by fishermen from Brittany since the early 16th century, and which they called "le petit nord".

French and English Relations

Until war broke out again in 1756, there seems to have been relatively little friction between French and British fishermen at Newfoundland. This was mainly because the French concentrated their fishing effort north of Cape St. John, and the British to the south of it. However, there was some concern at the advance of British settlement and fishing into Bonavista and Notre Dame bays, a process which accelerated when the French temporarily stopped coming to Newfoundland during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763).

By the Treaty of Paris (1763), France was allowed to resume fishing on the Treaty Shore, and was also granted the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon in compensation for the loss of Cape Breton. When the French returned to the "petit nord", they found they were no longer alone. British settlers and fishermen were now present in significant numbers, particularly south of Cape St. John, and the French government began to lodge protests.

The French argued that their right on the Treaty Shore was exclusive - that is, they had the sole right to fish there during the season. The British countered that the Treaty of Utrecht said nothing about exclusivity, and that the right was concurrent - fishermen from both countries could use the Shore which was, after all, British territory. The fundamental difference of opinion was never resolved.

However, there was an attempt to find a solution at the end of the American Revolutionary War. In the Treaty of Versailles (1783) between Britain and France, the boundaries of the Treaty Shore were changed to Cape St. John and Cape Ray. This left Bonavista and Notre Dame bays to the British, while providing compensation to France on the west coast. In addition, a declaration appended to the treaty provided that the British government would prevent British fishermen from "interrupting" the French fishery " ... by their competition", and would "cause the fixed establishments which shall be formed there, to be removed."

The French government reckoned, with some justification, that the British had now recognized their exclusive right, and the French do seem to have had the Shore more or less to themselves between 1783 and the outbreak of yet another war in 1793. This was to last until 1815, a long period during which fishermen resident in Conception Bay and elsewhere began regularly fishing on the "petit nord" in the summers. Known as the North Shore fishery, it resulted in an increase of settlers in the area.

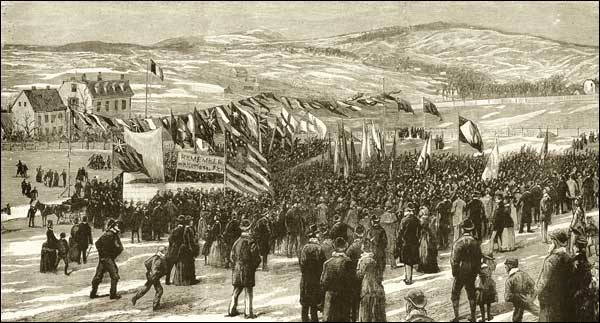

Returning to the Treaty Shore

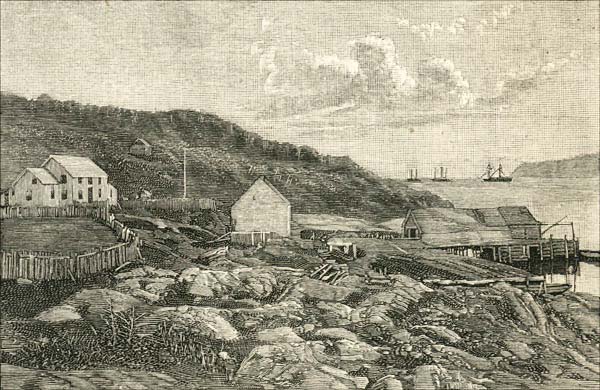

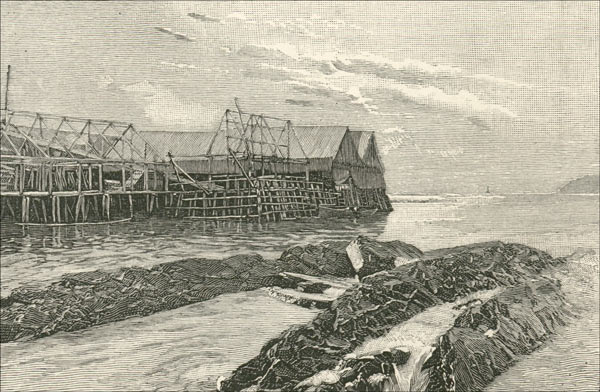

French fishermen returned to the Treaty Shore (and to St. Pierre and Miquelon) at the end of the war. Insisting on their alleged exclusive right, the French forced Newfoundland schooners fishing on the Shore to move on to the Labrador coast, and apparently pressured a significant number of settlers to move away. A limited number of families only were allowed to remain as gardiens (caretakers) of French fishing rooms.

The French fishery on the Treaty Shore declined from the 1830s onwards, while the local resident population increased significantly, especially from the 1860s. The Newfoundland government became increasingly impatient with French presence on the Shore - indeed, with the very existence of the treaties - and vigorously campaigned against French claims of an exclusive right, and the illegality of settlement. French and British naval squadrons on the Shore received an increasing number of complaints from their nationals, and there were several rounds of negotiations involving France, Britain and Newfoundland which attempted in vain to find a diplomatic solution satisfactory to all parties.

A Valuable Bargaining Chip

In spite of the decline in its Shore fishery - while that on the Banks increased dramatically - France was determined to hold onto its treaty rights until suitable and adequate compensation was offered. France knew it possessed a valuable bargaining chip at a time when relations with Britain were not always friendly. The Newfoundland government from 1857 onwards had to be involved in and consent to any new agreement. It was deeply concerned by French competition in European fish markets, and refused to agree to forms of compensation - such as free access to supplies of bait - which might in any way give an advantage to the French northeast Atlantic fishery. Newfoundland also wanted France to reduce or eliminate its fishery subsidies.

Given these hard-line positions, for many years the British government found it impossible to broker a new French Shore agreement. The situation changed in the early 20th century, as Britain and France began to move towards a general settlement of outstanding disputes. In this more positive atmosphere, a deal was struck that proved acceptable to both France and Newfoundland. The 1904 Anglo-French Convention, part of the "entente cordiale", provided that France would renounce its rights in Newfoundland under the Treaty of Utrecht, though French nationals could continue to fish - but not use the shore - within the traditional limits. Britain agreed to pay financial compensation to French outfitters with premises on the Treaty Shore, and also ceded to France an area of land in West Africa. The convention remained in force until 1972.

The Impact of the French Treaty Shore

The existence of the French Treaty Shore had a significant impact on Newfoundland's history. The settlement and development of the Shore was delayed as a result of the French presence, and its inhabitants received virtually nothing in the way of government services until the 1880s, when they were finally allowed representation in the legislature, and magistrates were appointed. Land and mining rights remained insecure until 1904. The route of the Newfoundland Railway was influenced by the Shore's existence, as was the decision to build the first newsprint mill at Grand Falls, and not on the west coast. In addition, the disputes over French fishing rights became a major focus for the Newfoundland nationalism that emerged from the mid-19th century.

The 18th century treaties relating to the French Shore created a situation unique in the British Empire - a protected foreign fishery carried on in British waters under its own laws and customs, supervised by both British and French naval squadrons, whose officers worked under very different interpretations of the respective rights of French and Newfoundland fishermen. Only now is this remarkable history coming into clearer focus.