The French Newfoundland Fishery in the 18th Century

The 18th century brought a number of difficulties for the French fisheries at Newfoundland. There was a catastrophic decline in inshore cod stocks from about 1710 into the late 1720s, but a more profound factor was Anglo-French warfare which disrupted the fishery, the trade and the markets. Moreover, the various peace treaties limited where and how the French could fish.

1713 Treaty of Utrecht

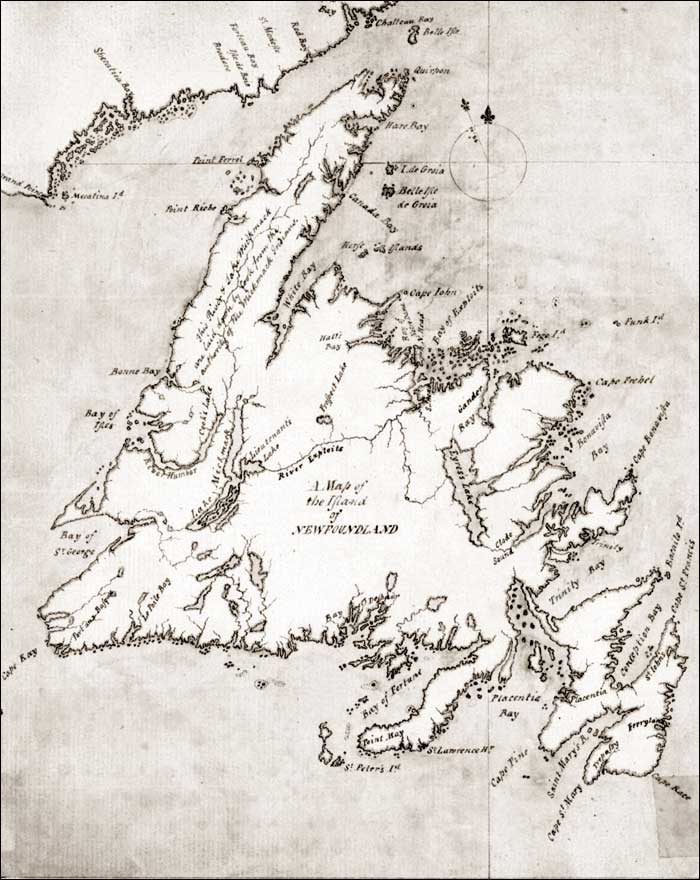

The first blow came with the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) which ended the War of the Spanish Succession. In this treaty, France recognized English sovereignty over the island of Newfoundland. As a result, the French left Plaisance (Placentia) and ceased fishing along the south coast. However, the French were allowed to continue fishing in season on the Newfoundland coast between Cape Bonavista and Pointe Riche, the petit nord, an area which came to be known as the French Shore, or Treaty Shore. Though France had to cede mainland Acadia (now Nova Scotia), it retained Cape Breton Island, now renamed Île Royale. There France created a new colony, and built the great fortress of Louisbourg. This became the centre of a flourishing fishery.

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) ended the French presence on the North American mainland. By the Treaty of Paris (1763) France ceded Canada to Britain, together with Labrador and Cape Breton. But the French were determined to retain their fishery in the region, and persuaded the British to renew their right to fish on the French Shore. In addition, Britain agreed to hand over the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, just off Newfoundland's south coast, to serve as a shelter ("abri") for the French banking fleet.

Treaty of Versailles

Further adjustments appeared in the Treaty of Versailles (1783), one of the web of international treaties negotiated at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The boundaries of the French Shore were changed - it was now to run from Cape St. John to Cape Ray - and French rights there defined in a declaration. Similarly, the French possession of St. Pierre and Miquelon was confirmed and clarified. The French Newfoundland fishery was again suspended during the Anglo-French wars that lasted from 1793 to 1815. The peace treaty restored the situation as it has been after 1783.

The French Fishery: Aftermath

The disruptions of war and increasing restrictions damaged both the sedentary and banking branches of the French fishery, and improved the position of the British and American fisheries. The French lost their markets for dry fish in Spain and Italy, for instance, and merchants were forced to rely on an increasingly unpredictable domestic market. Some ports abandoned the bank fishery altogether, or severely reduced their fleets. By the latter part of the 18th century, the French Newfoundland fishery was dominated by St. Malo and Granville. In the 1780s, 60 percent of French vessels fishing on the banks, and 80 percent of those fishing on the French Shore, came from these ports.

For all these problems, the French fishing effort remained impressive. Until the 1770s the French fleet was larger than the English - between 300 and 400 ships to the English 150 to 200 - though total production of fish was considerably lower. It has been estimated that between 1763 and 1815 the French produced approximately 350,000 metric tons; the estimate for Britain over the same period is 17 million metric tons.

The survival and relative success of the French fishery after 1763 was due in part to intervention by the French government, which did not want to lose this valuable nursery for seamen. First, an import duty was placed on foreign fish, both dry and green, entering France or the French West Indian islands. This effectively protected the French industry from competition in those markets. In addition, the government took measures to facilitate the distribution of fish within France itself.

Then, after 1783, the government provided subsidies (primes) to encourage the outfitting of fishing vessels, and the sale of fish in foreign markets. For instance, in the 1780s the government provided a subsidy, or bounty, of 100 livres per crew member to vessels going to the French Shore. The export bounty was between five and 12 livres depending on market. These were important incentives, though the export bounties were not at first very effective.

The French regarded their fishery at Newfoundland as a very important asset, both economically, and because it trained seamen. The maintenance of the fishery was seen as a vital object of national policy. As a result it did not die out amid the troubles of the 18th century, but survived to flourish after 1815.

In summary, then, over the course of the 18th century France was excluded from the coastal fisheries of what is now Atlantic Canada, but retained a right to fish on the Newfoundland French Shore and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and was given St. Pierre and Miquelon as a base for a bank fishery. This situation persisted into the 20th century.