Case Study of an Artifact

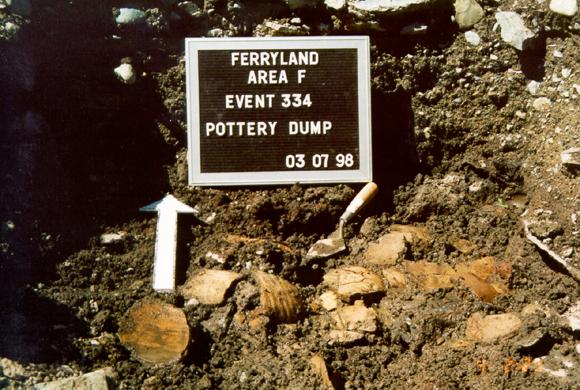

Of the approximate one million artifacts excavated to date from the Ferryland archaeology site, at least a third of those are represented by ceramic sherds. To the people of 17th-century Ferryland, coarse earthenware vessels were as much a part of everyday life as Tupperware is to the 20th-century inhabitants. Because the 17th-century plantation was destroyed twice during its occupation, many artifacts have suffered physical deterioration as buildings collapsed on top of them. This fact is clearly demonstrated in the photograph below which shows a pottery dump crushed into many fragments.

The fact that many of the sherds still maintain their original orientation in the burial environments makes assembling the sherds into vessels much easier for the conservator. The trick for the conservator however is to calculate how it is that the fragments can be removed from the soil and attain their original orientation.

The trick used by conservators to excavate fragmented artifacts from the ground is called blocklifting. Blocklifting artifacts from the burial environment simply means you excavate the object plus the soil surrounding the object. Some sort of support is given to the object (gauze/wax or foil) with the soil sometimes being consolidated (synthetic material used to make the soil rigid). Therefore the object, or fragments of an object, remain in their original orientation of burial.

The photo above shows part of a sgraffito bowl prior to blocklifting. The section of bowl represented consists of approximately 300 ceramic fragments. Prior to disassembling the bowl for mechanical cleaning, the sherd orientation would be mapped. This mapping technique helps the conservator to assemble the fragments after cleaning.

The bowl after conservation is shown in the photo below.

Because a full profile of the bowl is represented (rim, body and base) the remaining vessel can be reproduced using plaster similar to the example below. A fully restored sgraffito bowl is shown alongside.