The Impact of the Anglo-French Wars, 1793-1803

Coming so soon after the massive market collapse of the late 1780s, the wars had a devastating effect on the migratory fishery. The raid by Admiral de Richery in 1796 caused panic and some damage. In the same year, Spain entered the war as an ally of France, and closed its markets to British trade. British saltfish could enter Spain clandestinely through Portugal, but this caused so much fish to pass through Portuguese entry ports that prices there were driven down. And when Portugal was threatened by invasion in 1800, that market became too unreliable for merchants in the fish trade. As a result, merchants increased the volume of fish sent to the West Indies. Overall, export levels remained reasonably high (400,000 quintals in 1800), but trade conditions generally were poor, particularly since there was growing competition from Scandinavian countries as well as from the more familiar Americans, who were exporting nearly as much fish at this time as the British.

Economic Struggle

The number of bankruptcies during the first decade of the war reflected the uncertain state of the Newfoundland fish trade. Not only were markets difficult, but risks and insurance rates soared in wartime, adding to a merchant's overhead. The labour shortage inflated wages within the fishery, the merchant marine and the shipbuilding industry. Shipbuilding costs also increased because of wartime interruptions in the supply of materials used to construct and outfit ships and vessels. These higher operating costs in turn caused wartime freight rates to increase.

The result was that British merchants began to transfer capital out of the fishery and into the carrying trade - fishery profits had become uncertain, while the profits from shipping and trade were protected by rising wartime freight rates. The number of British-based migratory fishing ships decreased dramatically, especially in the banking fleet. This offshore fleet consisted of 82 vessels in 1793; by 1807 it had dropped to 33, of which 30 were based at St. John's.

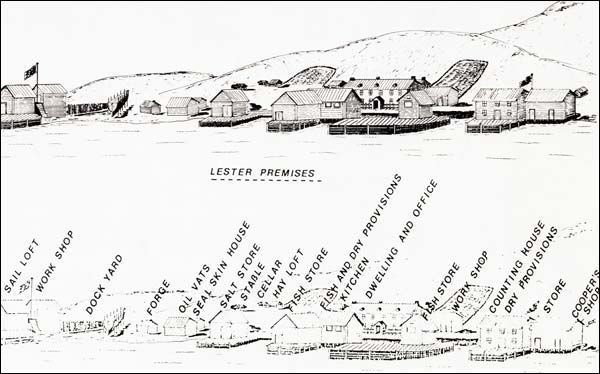

Merchants were looking for dependable investments. For example, Poole firms operating at Trinity re-directed some of their capital from the bank fishery to the carrying trade. Others diverted their bankers to the northern cod fishery, the new spring seal fishery, or the inshore fishery along the Treaty Shore which the French had abandoned as soon as war broke out. By 1801, only one banker still operated out of Trinity. Lester and Company had a fleet of 20 vessels in 1788, about half of them bankers; in 1800 the fleet had shrunk to 11, nearly all of them engaged in the carrying trade.

The wartime period, then, was not disastrous for those merchants who withdrew from the fishing industry but maintained their investment in the fish trade. The British government was not beset with widespread cries of ruin, as had occurred in previous wars, and the "decline" of the migratory fishery does not mean that an activity had ended, but that it had been transformed. West Country merchants had long been reducing their direct involvement in the fishery in favour of other activities, such as the supply and carrying trades. The market glut of 1788 to 1791, and the onset of war in 1793, simply accelerated an established trend. Production levels in the fishery remained greater than anything the British fishery had been able to deliver before 1750. This was because the resident fishery, for the first time ever, was able to take up any slack in production caused by the contraction of the migratory fishery.