Early 20th Century Exploration

Exploration in Newfoundland and Labrador occurred on a smaller scale during the first half of the 1900s than in previous centuries. Adventurers and geologists from North America and Europe arrived at Labrador to study its vast and largely uncharted interior, while the island of Newfoundland served as a taking off point for some of the world's first transatlantic flights.

In addition to attracting foreign expeditions, the country also produced a number of local explorers who helped map the globe's northern regions. Most notable among these was master mariner Robert (Bob) Bartlett, who achieved international recognition for his work in Robert Peary's North Pole expeditions, as well as for his decades of Arctic exploration.

Mapping the Labrador Interior

Canadian geologist Albert Peter Low and Finnish geographer Väinö Tanner made significant contributions to the world's understanding of Labrador during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Tanner visited Labrador in 1937 and 1939 to study the region's geology, geography, flora, and fauna, which included its local inhabitants. He received funding from the governments of Finland and Newfoundland and Labrador to complete the work and recorded his findings in the 1944 publication, Outlines of the Geography, Life and Customs of Newfoundland-Labrador.

Decades earlier, Low had explored and mapped much of the Labrador interior. He discovered large iron ore deposits in western Labrador – which eventually led to the development of mining operations there – and published his findings in the 1896 Report on Explorations in the Labrador Peninsula along the East Main, Koksoak, Hamilton, Manicuagan and Portions of Other Rivers in 1892-93-94-95.

Despite the thoroughness of Low's work, considerable mystery still surrounded land to the west and north of Hamilton Inlet. This attracted a handful of Canadian and American adventurers who wished to explore what they considered one of North America's last uncharted frontiers. Most famous among these were Leonidas Hubbard, Mina Hubbard, Dillon Wallace, and George Elson.

Leonidas Hubbard's 1903 Expedition

On 15 July 1903, 31-year-old American journalist Leonidas Hubbard led a small expedition into the Labrador interior from the Hudson Bay Company's post at North West River. His plan was to paddle west from Grand Lake to the Naskaupi River and then into Lake Michikamau. From there, he hoped to continue north along the George River to observe the annual caribou migration across Labrador - something no white man had done before - and make contact with Innu living in the area. Depending on the weather and lateness of the season, the party would at that point either continue north to Ungava Bay or make a return trip to North West River.

Hubbard invited his friend Dillon Wallace, a New York attorney, to join the expedition and hired George Elson, a Métis woodsman from Ontario, to act as its guide. A series of mistakes and bad luck, however, hampered their progress from the outset. Hubbard based his plans on A.P. Low's maps of Labrador which, although the most accurate at the time, mistakenly showed only one river flowing into Grand Lake instead of five. As a result, expedition members mistook the Susan River for the Naskaupi, which sent them badly off course just one day after leaving North West River. A string of other problems compounded the error. Bad weather slowed their progress, an unusual scarcity of game made hunting difficult, and neither Hubbard nor Wallace packed enough clothing and footwear to withstand the elements.

Cold, hungry, and disoriented, the party decided to turn back on 15 September. Hubbard's condition, however, quickly deteriorated and by mid-October it was apparent to all expedition members that he could go no further. Wallace and Elson prepared a camp for him along the Susan River and then proceeded east together. The two men planned to retrieve a store of flour they discarded on the journey out and then part ways – Elson was to continue to North West River for help, while Wallace was to return to Hubbard's camp with some of the flour.

Elson arrived at a trapper's house near Grand Lake about a week later and alerted its inhabitants of Hubbard's location. When rescuers arrived on 30 October, they found Hubbard dead and Wallace in a highly confused and weakened condition. In three months, Wallace's weight dropped from 170 to 95 pounds and gangrene appeared in his foot. His rescuers helped nurse both him and Elson back to good health and the two men accompanied Hubbard's body back to New York for burial in May.

In 1905, Wallace published a best-selling book about the expedition, The Lure of the Labrador Wild. He also announced an intention to return north and complete the work that killed his young friend.

Mina Hubbard

Mina (Benson) Hubbard learned of her husband's death on 22 January 1904 after receiving a 10-word telegram from Wallace: “Mr. Hubbard died October 18 in the interior of Labrador.” She sank into deep mourning and hoped Wallace's book would pay tribute to Leonidas' memory. However, when Hubbard read an early manuscript of Lure in November 1904, she felt it unfairly depicted her husband as a naïve and inept adventurer. She also believed Wallace was trying to appropriate the praise and recognition that rightfully belonged to Leonidas by planning a second trip north.

Angry and wishing to finish her husband's work, Hubbard secretly planned her own Labrador expedition. She invited George Elson to join the team, as well as Gilbert Blake, a Labrador trapper who helped rescue Wallace in 1903. She also hired two of Elson's friends from the Hudson Bay area, Job Chapies and Joseph Iserhoff.

The rival expeditions departed North West River on the same day, 27 June 1905. Although both parties hoped to reach Ungava Bay by the end of August, they chose different routes and methods – Hubbard adhered to the course her husband plotted in 1903 and took enough food and supplies to last the entire trip; Wallace, on the other hand, followed an old Innu portage route and packed a lighter load, hoping to catch wild game along the way.

In the end, Hubbard's expedition proved the most efficient and successful. She reached Lake Michikamau on 2 August, observed the migrating caribou herd on 8 August, and visited two Innu settlements before arriving at Ungava Bay on 27 August. She later produced accurate maps of the Naskaupi and George River systems, which were accepted by both the American and British Geographical Societies, and provided some of the first photographic and written descriptions of the caribou migration across Labrador and of the lifestyles of the Innu. Hubbard also published an account of her journey, A Woman's Way through Unknown Labrador.

Wallace's party, meanwhile, became lost a few times along the trail and had to spend much time and energy hunting for food. Its members arrived at Ungava Bay about seven weeks after Hubbard on 16 October 1905. Although Wallace supplied new information about land to the north of the Naskaupi River, geographical authorities generally accepted Hubbard's work as the most substantial and useful. He did, however, publish a book about his adventure, The Long Labrador Trail, which received more popular acclaim than Hubbard's. Despite Hubbard's success, it was likely less difficult for the public at that time to accept Wallace in the role of explorer. As Roberta Buchanan points out in The Woman Who Mapped Labrador, “exploration was a man's game in the early 1900s” (27) and by challenging that perception, Hubbard risked ostracization.

Aviation in Newfoundland and Labrador

While Labrador attracted a handful of explorers to its interior during the early 20th century, the island of Newfoundland became a popular destination for aviation pioneers wishing to cross the Atlantic Ocean by air. In April 1913, the London Daily Mail offered a £10,000 prize for piloting the first transatlantic flight from Canada, the United States, or Newfoundland and Labrador to the United Kingdom. The newspaper stipulated the flight must be non-stop and take no longer than 72 hours to complete. Newfoundland's proximity to Europe made it a popular taking-off point for aviators anxious to win the prize and a place in history.

In May 1919, Lieutenant Commander Albert C. Read of the United States Navy and his crew flew from New York to England with a stopover in Trepassey. Although not a non-stop flight and therefore ineligible for the £10,000 prize, Read's voyage is considered the world's first transatlantic flight. The following month, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown successfully completed the first non-stop transatlantic flight, after taking off from St. John's on 14 June and landing at Ireland the next day. The two men received the Daily Mail prize and were knighted by King George V.

In the coming years, Newfoundland and Labrador continued to attract aviators from all over the world, including American pilot Amelia Earhart, who completed the world's first transatlantic solo flight by a woman after taking off from Harbour Grace on 20 May 1932 and landing at Northern Ireland 13 hours and 30 minutes later.

Explorers from Newfoundland and Labrador

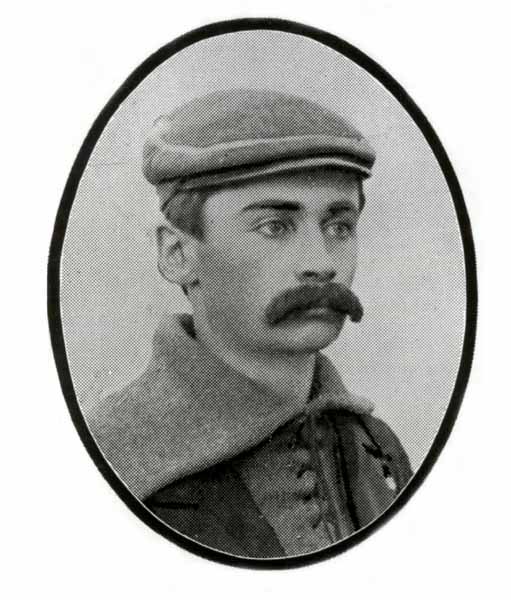

As foreign explorers continued to arrive at Newfoundland and Labrador during the first half of the 20th century, a number of local adventurers left the country to explore other parts of the globe. These were often the ship captains and sailors who joined various Arctic expeditions to help map the world's northern regions. Perhaps the most famous example is Brigus master mariner Bob Bartlett, who achieved international acclaim for his work in Robert Peary's three North Pole expeditions from 1898-1909.

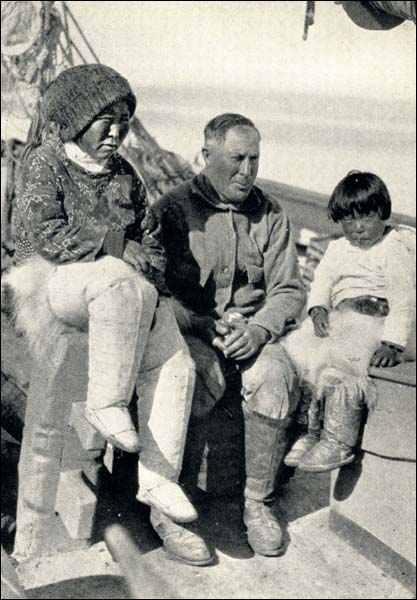

Bartlett also made more than 14 voyages into the Arctic aboard his vessel, the Effie M. Morrissey, often taking crewmembers from Newfoundland and Labrador with him. Recognizing the scientific importance of his voyages, Bartlett frequently returned with photographs, film reels, and scientific data that greatly contributed to the world's understanding of the north. Before he died in 1946, Bartlett donated millions of Arctic specimens, including whale skeletons, water samples, and different types of plant life, to the Smithsonian Institute, the American Museum of Natural History, and various other scientific societies, universities, and museums.