Women and the Economy in the 19th Century

The majority of women in Newfoundland by the early 1800s were residents who prosecuted the family-based fishery. Others were either Indigenous or migrant wives and servants from the British Isles. Migrant women generally belonged to the middle and upper classes, while single women typically came from poorer households in search of employment overseas.

Since men generally composed the crews of fishing boats and larger vessels, historians generally placed male labour at the centre of the fishery, and thus the Newfoundland and Labrador economy in general. However, women's economic roles in all areas of the fishing industry were extremely important. Their work in the fishery, as well as in agriculture and domestic labour, combined to make women the backbone of the household economic unit.

Women and the Fishery

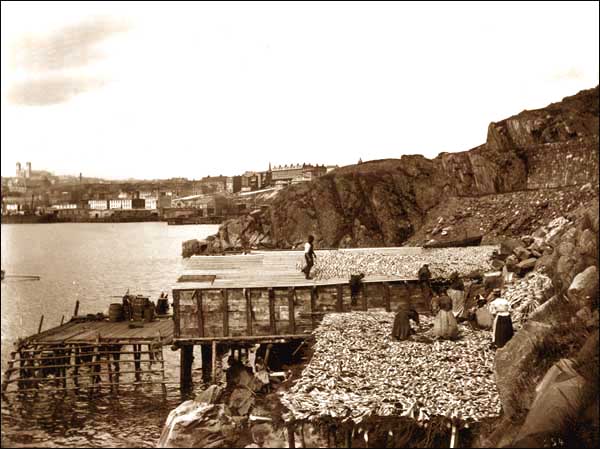

The fishing industry in 19th-century Newfoundland consisted of an inshore fishery along the coast, a Labrador fishery, and an offshore bank fishery. The inshore fishery was a household operation in which women's work was vital. Although men built boats and did the actual fishing, women were largely responsible for processing the catch for sale to the merchants, and they exercised considerable authority when fishing was most intense. The fisher's wife assumed the role of 'skipper', which placed her in charge of the shore work. For the peak period of the summer fishery, women devoted nearly all of their labour efforts to 'making' fish and put all of their other duties on hold.

This work required much precision and skill. The initial preparation was usually done in an assembly line, beginning with the 'header' who removed the guts. A 'splitter' would then de-bone the fish for the 'salter,' who salted and stacked the fish for curing. Workers then spread the fish on a flake for drying, and carefully watched the product to prevent it from sunburn. After the drying was completed, the shore crew had to carefully stack the fish for shipment to the merchant. For a period of two to three months, shore work occupied nearly all of women's time and allowed for very little rest.

Women's contribution to the fish-making process was crucial since it determined the final value of the product that was sold to the local merchant. At season's end, the family's economic return naturally rested on the quantity and quality of the fish sold. If cured fish did not contain the right amount of salt and moisture, it was of a poorer grade and marketed at lower prices.

Shore work was organized along practical lines rather than ideals of male and female labour. Time did not allow men to process their catch, so women helped cure the fish while their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons were at sea. Shore work was a source of pride for many women who viewed it as a vital contribution to the 19th-century family economy.

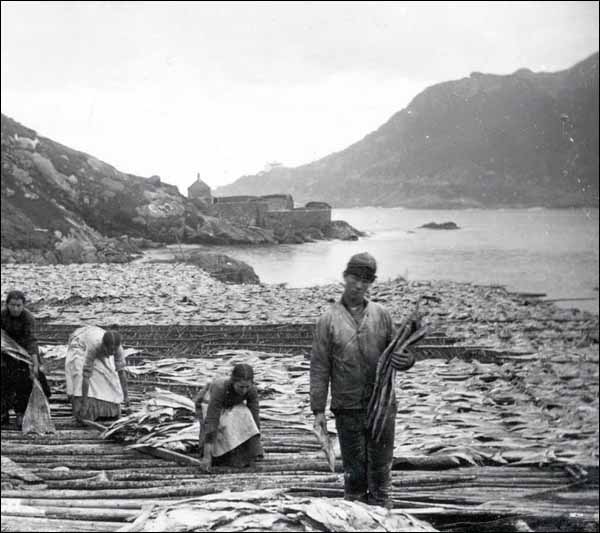

After the Napoleonic and Anglo-American Wars, more Newfoundland fishers migrated to Labrador to fish in the summers. Labrador offered bountiful fishing grounds and a use for sealing vessels not otherwise needed during the summer months. The Labrador fishery consisted of 'floaters' who lived on their boats and fished along the Labrador coast, and 'stationers' who set up living quarters on shore and fished in small boats. Floaters brought their catch back to Newfoundland for processing while stationers processed it on shore.

Stationers tended to be the men, women, and children of fishing households who simply moved the location of their work in the fishery from the coast of Newfoundland to the coast of Labrador for the summer. The floater fishery relied more on hired crews of men and women. Women involved in the floater fishery were typically young and single, and their primary responsibility was cooking for the fishermen. Such cooks prepared several daily meals and snacks for male fishing crews, and had to ensure they could ration food supplies for the duration of the trips. Cooks also split, salted and stored the fish whenever the crews were shorthanded.

Domestic Work

In the home, women's duties were never-ending. Preparing meals was a constant responsibility, since the men typically ate several times a day. There were usually four large meals and several light snacks or 'mug-ups.' With only a small variety of foods to work with, Newfoundland and Labrador women had to vary the family's diet as best they could with only a limited number of ingredients. Most meals consisted of fish and potatoes, which women managed to prepare in a variety of ways. Cooking was a major source of women's pride, and bread making was a particularly coveted skill. Baking occurred at least once a day, twice for larger households. Prior to packaged yeast, women in Newfoundland and Labrador grew their own hops.

But cooking was only a fraction of women's domestic work. With money so scarce, families had to be resourceful with all the materials they had. Most women were skilled at spinning wool and knitting, and they made most of the clothing that the family wore, including socks, mittens, pants and sweaters. Household cleaning was another ongoing task, which required scrubbing floors, cleaning beds, and hand washing clothes, all of which were carried out on a daily basis. Women also had to balance their work amongst the shore crew with all of their normal duties during the fishing season. Their role becomes even more remarkable considering the added responsibility of raising children.

Subsistence Economy

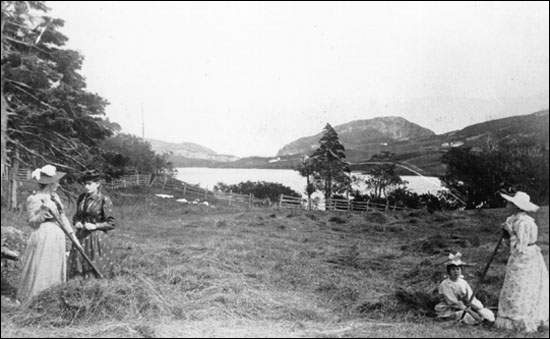

To avoid complete reliance on merchant credit, households sought ways to provision themselves with the food and materials needed for survival. Agriculture, though quite difficult given the island's poor soil and harsh climate, allowed families to be slightly more self-sufficient. After the men dug the earth, family gardens were the women's responsibility. Women cleared the land of rock, fertilized the land, planted the vegetables, and tended to the garden. This work was extremely labour intensive and required much physical strength.

Most families owned livestock, including sheep, chickens, horses, cows, pigs, and goats. With the men away fishing, women took responsibility for the animals. They milked cows, sheared sheep, and processed the wool for making clothing and other household materials such as bed sheets, quilts, and pillows. These tasks required another set of valuable skills that made a woman's work all the more important to her family's survival.

Berry picking was also primarily a woman's duty, and one that contributed much to the family income. Women used berries – including blueberries, partridgeberries, bakeapples, strawberries, and raspberries – to make jams, jellies and wine, which they bartered for valuable provisions to help the family through the winter.

Household finances were the woman's responsibility as well. At the end of the fishing season, the husband could only settle up with the merchant after consultation with his wife, who kept close track of all transactions and debts incurred. Knowledge of household accounts lay with the matriarch, who often became involved when disputes arose between family and merchant. A family's livelihood rested heavily on the woman's managerial skills.

Women and Wage Labour

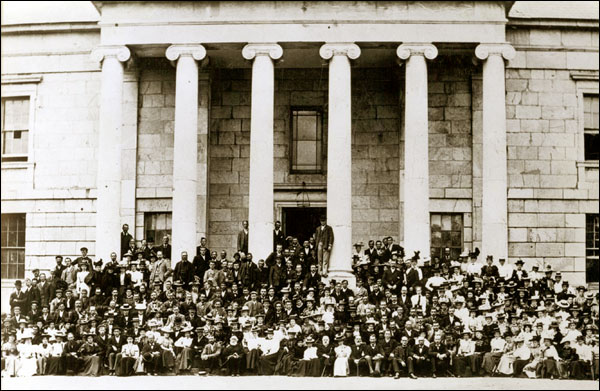

In the early 19th century, the majority of paid labour for women was service work. Census records and newspaper advertisements from this period show women worked as midwives, gardeners, washerwomen, dressmakers and on occasion, innkeepers. By the latter part of the century it became more common for women in St. John's to work as wage earners employed as domestics, clerks, and factory workers. Most of these women were single and childless; married women sought wage work that could be carried out domestically, such as washing and sewing. The most common women wageworker in St. John's was the servant, typically an outport girl who assisted mercantile families with domestic duties and worked with the fishery. Domestic servants cooked, washed, cared for children, and tended to family gardens and livestock.

Domestic work was demanding in nature and most servants worked very long hours for employers who expected them to be available at all times of the day. Moreover, wages were low and relationships between servant and family were often volatile. Court records from this period include numerous employment disputes over wage payments and allegations of mistreatment by masters.

For more information on the women who lived and worked in Newfoundland and Labrador visit Coastal Women in Newfoundland and Labrador Prior to Confederation on the Maritime History Archive (MHA) website.