Tourism before Confederation

Newfoundland's tourism industry dates back to the 1890s, when advances in rail and ocean transportation made the colony more accessible than before. The government saw tourism as a way to diversify the economy, create jobs in rural areas, and lure potential investors. Although the industry made important cultural and economic contributions, it faced many challenges. A lack of adequate roads, accommodations, and other facilities was an ongoing problem until well after Confederation.

Newfoundland's underdevelopment, however, helped to shape its tourism campaigns. The colony was promoted as a rustic paradise where visitors could escape to nature and a simpler way of life. Advertisements targeted wealthy big-game hunters and anglers, disillusioned middle-class city dwellers, and expatriate Newfoundlanders. Brochures showed picturesque fishing villages, majestic scenery, and abundant wildlife. Many themes of the pre-Confederation period are still used by the tourism industry today.

Steam, Rail, and Tourism

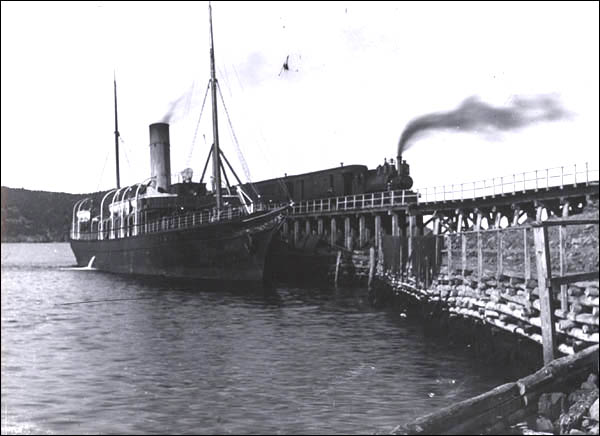

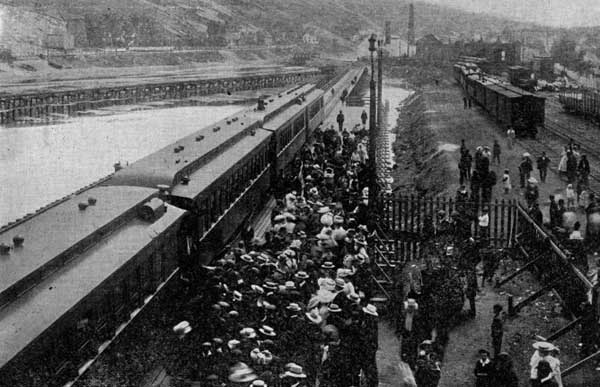

Long before a formal tourism industry emerged in Newfoundland and Labrador, the occasional visitor arrived from North America and Europe. Most were wealthy and educated men - typically naturalists, adventurers, artists, sportsmen, and academics - attracted to the colony's wilderness and outport way of life. However, no organized effort was made by the government or local business to attract visitors until the late 1890s. In that decade, a trans-island railway began operating, with its associated coastal steamers and a ferry to mainland North America. Large numbers of people could travel to and from the island with relative ease.

The Reid Newfoundland Company, which operated the railway, recognized the economic potential of a tourism industry. It produced some of the colony's first brochures and guidebooks. Many targeted wealthy sportsmen by promoting the island's hunting grounds and salmon rivers - areas made newly accessible by the railway (and often controlled by the Reid company through its land grants). Titles included: Fishing and Shooting in Newfoundland and Labrador: Their Attractions for Tourists and Sportsmen (1903) and Newfoundland's Attractions for Travellers, Tourists, Health Seekers and Sportsmen (1912).

The occasional travel journalist also provided free promotion for the colony. Most prominent was Norman Duncan, who first visited the colony in 1900 to report on Sir Wilfred Grenfell's missionary work for the geographical adventure magazine McClure's. Inspired by his trip, Duncan returned to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1901 and 1906, eventually writing more books and essays about outport life and what he called "the real Newfoundland" (qtd. in O'Flaherty 96).

The government supported the industry as well. It saw tourism as a way to diversify the economy and introduce the colony to wealthy capitalists who might invest in local business and industry. It paid for advertising and passed a series of game laws, which largely protected caribou as a tourism resource by limiting local residents' access to this important food source. The colony issued more than 100 caribou licenses annually in the first decade of the 1900s. The collapse of the caribou herds in the 1920s, however, interrupted the development of sports tourism, although salmon fishing remained an important attraction.

Nature and Nostalgia

Two other groups of tourists were also targeted: middle-class urbanites interested in reconnecting with nature and homesick expatriates living in the United States and Canada. At the turn of the century, a "back to nature" movement emerged in North America and Europe to counter feelings of alienation and depression spreading among city dwellers - particularly educated businessmen and professionals. The colony's promotional materials catered to this group by focusing on its rugged coastlines and rural areas.

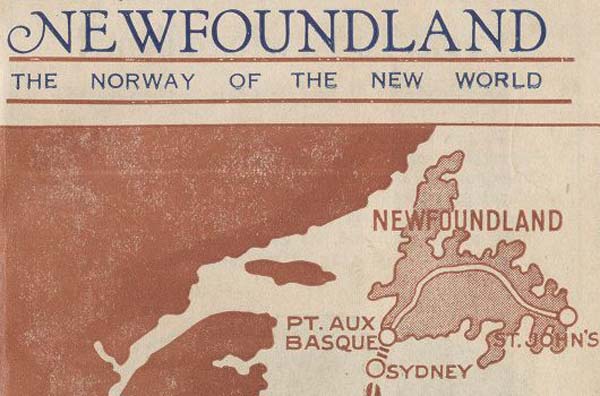

Links were also made to well-known tourist destinations. Newfoundland was "the Norway of the New World," but also bore "a striking resemblance to the Highlands of Scotland" (Newfoundland Railway Company 8, 9). At the same time, it offered visitors a unique experience through its distinct cultural heritage and outport way of life. Disenchanted city dwellers would return to their homes rejuvenated and enriched by their contact with nature and a simpler lifestyle.

Descriptions of a similarly romanticized Newfoundland were used to lure expatriates back for vacations, but were often accompanied by references to a happy childhood and family life. The island was a place frozen in time, where disenchanted adults could reconnect with a more satisfying time. They were invited back for family vacations and the occasional group reunion.

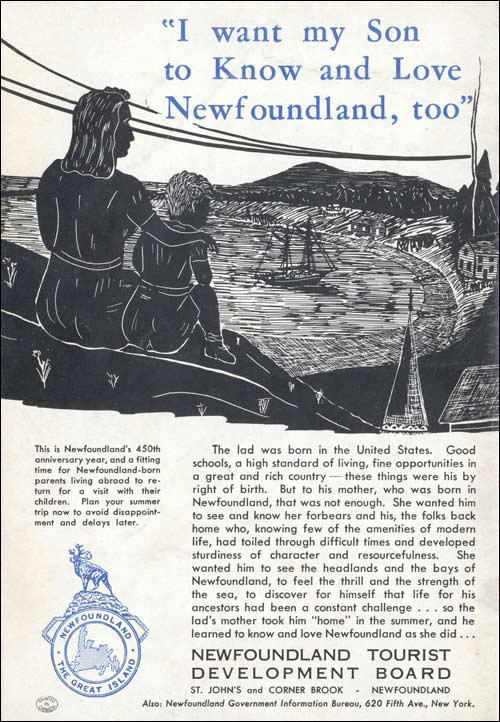

One such event was "Old Home Week", which the government helped organize in 1904. From 3-10 August, approximately 600 Newfoundlanders arrived at St. John's from the United States. Songs and promotional materials emphasized Newfoundland pride and identity. The colony was referred to as a "Homeland" or "Old Land" which maintained emotional ties to its former residents: "Avalon is calling you, calling o'er the main,/ Sons of Terra Nova, shall she call in vain?" asked then Governor Sir Cavendish Boyle in a song he wrote for the event. Similar themes of nostalgia and ties to an idealized homeland were repeated in future campaigns. "I want my son to know and love Newfoundland too," said a mother in one magazine advertisement from the 1940s.

Common to all tourism campaigns was a simplified and idealistic vision of Newfoundland and Labrador. The colony was a place outside of social, political and economic strife. Outport people were hospitable, simple, open, and - despite their poverty - happy with their place in the world. The landscape was a scenic paradise unspoiled by development or litter.

Historian James Overton suggests tourism campaigns did more than draw tourists and their dollars to the colony - it helped to define its people and shape its cultural heritage. "A particular version of Newfoundland was "invented" for tourists. But not just for tourists. The same totems, icons, and images highlighted for tourists came to be seen as the essential symbols of Newfoundland national identity ... From the late nineteenth century a host of local writers emerged to sing the praises of Newfoundland's fisher-folk and scenery. Ideas about landscape became central to notions of nationhood" (Overton Making 17).

Government and Business Support

Although Newfoundland's underdevelopment was central to its advertising campaigns, it also obstructed tourism. Government and business soon recognized the industry would stagnate without better accommodations, transportation, and other amenities. Major efforts were undertaken in the 1920s. The government upgraded and built roads, increasing the mileage from 130 in 1925 to 731 in 1929. It also marked and restored some historic monuments.

In 1925, the Board of Trade created a Newfoundland Tourist Publicity Commission, which received government funding two years later. The commission set up information bureaus in London and Boston, organized illustrated lecture tours to promote the island's culture and history, and prepared tourism literature. The number of tourists increased from about 5,000 in the mid-1920s to 8,347 by the end of the decade. The commission was placed under the control of the Department of Natural Resources in 1935 and reconstituted as the Newfoundland Tourist Development Board.

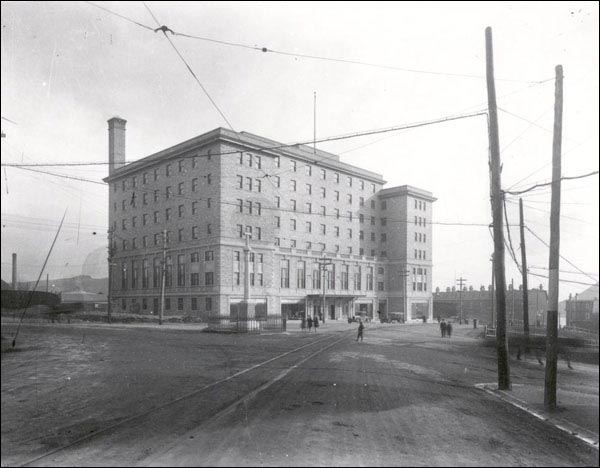

Businesspeople also opened hotels on the island. Most were located at St. John's, and included the Commercial Hotel, Cochrane House, the Atlantic Hotel, and the Central Hotel. In 1926, the Quebec company T.E. Rousseau Limited opened the 142-room Newfoundland Hotel. High operating and construction costs forced the company out of business in 1931, and the hotel was taken over by the Department of Public Works. By then, hotel accommodations had expanded elsewhere on the island to include Gleneagles Lodge near Gander Lake, the Glynmill Inn and Humber House at Corner Brook, and the Beach Grove Hotel at Spaniard's Bay.

Tourism suffered a setback in the 1930s and 1940s because of the Great Depression and Second World War. When peace was restored, expatriate Newfoundlanders remained a staple of the tourism industry. By then, post-war affluence had made motorized tourism popular among many North American families who could suddenly afford their own cars. Newfoundland's lack of roads and motels, however, prevented it from tapping into this lucrative new market. Developing the infrastructure that would attract the modern tourist became a central focus of Joseph Smallwood's Liberal government in the immediate post-Confederation period.