Economic Impacts of the Cod Moratorium

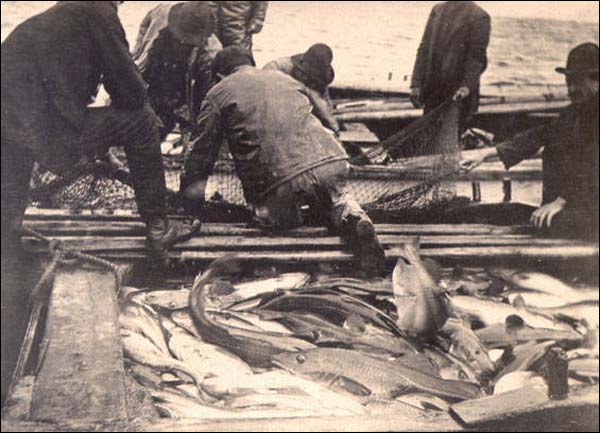

On 2 July 1992, the Canadian government imposed a moratorium on the Northern cod fishery along the country's east coast. Decades of over-fishing had severely depleted cod stocks and government officials hoped the moratorium would allow the species to rebuild. The closure ended almost 500 years of fishing activity in Newfoundland and Labrador, where it put about 30,000 people out of work. Fish plants closed, boats remained docked, and hundreds of coastal communities that had depended on the fishery for generations watched their economic and cultural mainstay disappear overnight.

To help displaced workers adjust to post-moratorium society, the federal government introduced a variety of financial aid, retirement, and retraining programs. At the same time, a burgeoning shellfish industry absorbed some unemployed workers, while others found work in a growing tourism sector. Nonetheless, unemployment levels have remained high since the moratorium, resulting in heavy reliance on government aid and in increased out-migration – in the 10 years following the moratorium, the province's population dropped by a record 10 per cent.

Financial Aid Programs

The moratorium sparked the single largest mass layoff in Canadian history and put about 30,000 people from Newfoundland and Labrador out of work, representing about 12 per cent of the province's labour force. Although most fishing people realized the cod stocks were in trouble, the closure caught many off guard. Most had worked in the fishery since high school and did not know where else to turn for employment; some had invested tens (or even hundreds) of thousands of dollars in vessels and fishing gear, which the moratorium rendered useless and which would become even more difficult to pay off without steady employment.

Accompanying the government's announcement of the moratorium was its introduction of an aid package for unemployed fishers and plant workers. Known as the Northern Cod Adjustment and Rehabilitation Program (NCARP), it provided weekly payments to out-of-work fishing people based on their average unemployment insurance earnings between 1989 and 1991, often ranging from $225 to $406 a week. NCARP participants were also required to enrol in training programs for work in other areas or accept early retirement packages. Approximately 28,000 of the province's fishers and plant workers received income support benefits under the program.

NCARP ended in May 1994 and was immediately replaced by a second relief program known as The Atlantic Groundfish Strategy (TAGS). Like NCARP, TAGS tried to reduce the number of people dependent on the fishery in rural communities. Overcapacity – too many fishers harvesting too few fish – had been a serious problem in the cod fishery and one that government officials did not want to see happen in the province's other fisheries. To encourage workers to leave the industry, TAGS required applicants to retrain for work in other fields or accept retirement packages. It also provided participants with regular weekly payments ranging from $211 to $382. Although the federal government intended TAGS to remain active until 1999, the $1.9-billion program ran out of funds in May 1998.

Both NCARP and TAGS met with limited success. Although the programs gave out-of-work fishing people a degree of financial security during difficult times, they did not adequately prepare them for work in other fields, nor did they significantly reduce the number of people dependent on the fishery. According to economist William Schrank, the number of full-time fishers has remained largely unchanged since before the moratorium, although many part-time harvesters have left the industry. In 1991, for example, the fishery employed about 14,000 full-time and 10,000 part-time fishers; of that number, about 12,000 qualified for employment insurance (EI). In 2002, a decade after the moratorium, the number of EI-eligible fishers jumped to 13,700. In contrast, the number of fish plant workers dropped from 25,160 in 1990 to 14,770 in 2001.

Although NCARP and TAGS applicants had to attend various training programs – including literacy training, adult basic education, university courses, and entrepreneurial training – the courses often did not prepare participants for entry into the labour market, nor did they adequately accommodate the needs and abilities of the fishing people taking them. Individuals who left high school years or even decades earlier to work in the fishery were suddenly thrust into an unfamiliar and often intimidating academic environment. Some did not complete their programs, while others found they were of no practical use to their future lives. Moreover, with no local employment alternatives available to absorb the thousands of unemployed fishers, most remained in the fishery or left the province to find work elsewhere.

The Fishery and the Provincial Economy

In the years preceding the moratorium, cod was the mainstay of the provincial fishery. Although fishers also harvested halibut, capelin, lobster, shrimp, crab and other species, the combined earning from these fisheries was about equal to the cod fishery alone. In 1990, for example, the total landed value of all species was $277 million, of which cod accounted for $134 million, or 48 per cent.

Although the value of total landings fell to $172 million in 1992, the year the moratorium came into effect, the growth of a lucrative shellfish industry allowed the industry to quickly rebound. By the end of 1995, total landings had reached $321 million, despite the almost complete absence of codfish. Much of the increase was due to snow crab landings, worth about $181 million in 1995. The provincial Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture reported $478 million in total fish landings for 2007, of which shellfish accounted for $383 million.

Despite the profitability of the shellfish industry, it today faces problems similar to those of the pre-moratorium cod fishery. There is an overcapacity in the fish processing sector, the market is flooded with shellfish, and some harvesters are reporting the size and number of some shellfish species are shrinking. Although the government has reduced quotas for crab and other shellfish, some fishing people and scientists worry the stocks are being depleted beyond their ability to rebound.

Fishing People

The Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture reported in 2007 that 12,725 fishers and 12,080 processors worked in the province, which accounted for approximately 11 per cent of the labour force. Although most fishing people now work in the profitable shellfish industry, their individual earnings are low and often have to be supplemented with EI payments. In 2001, fishers reported an average income of $25,400, while plant workers earned about $19,701. Both figures take into account about $10,000 in EI payments, and both figures were considerably lower than the provincial average annual income of $32,000.

Although EI payments are a necessary component of fishers' and plant workers' incomes, heavy dependence on them places some fishing people at greater risk of injury, stress, and other problems at the workplace. The need to accumulate enough hours to qualify for insurance, coupled with a lack of alternative job opportunities, may deter some workers from taking time off due to sickness or injury, while at the same time persuading others to remain in unhealthy or potentially dangerous work environments.

As of 2008, the cod moratorium remains in place and it is unknown when or if the stocks will rebound. Crab, shrimp, and other shellfish have replaced cod as the dominant species harvested and the province exports most of its seafood to the United States and China. The fishery provides direct employment for about 25,000 workers and there are 143 fish plants scattered across the province. Incomes, however, are low and overcapacity remains a problem in the fish industry.