Roads for Rails: The Closure of the Newfoundland Railway

Changing Transportation Patterns

Construction began on the Newfoundland railway in 1881, and the track was completed from St. John's to Port aux Basques in 1898. The railway was intended to provide a trans-island transportation route, and more importantly, to help diversify the economy by making it possible to exploit the island's interior resources, especially forests and minerals. It was believed that forestry and mining projects, as well as agriculture, would make the population less reliant on the fishery.

Given the poor road system, the railway was the only means of land transportation available for much of the early 20th century. People and goods had to travel either by boat or by train. However, by 1949, when Canadian National Railways (CN) became responsible for the railway in Newfoundland, the situation had started to change. Airports at St. John's, Gander and Stephenville had been built by the military during the Second World War. Civilian air travel started as early as 1942, and became more common after the war. Cars were becoming popular too, and the number of automobiles in Newfoundland rose from about 4,000 in 1935 to 13,000 in 1949, and to 87,000 in 1965. That year, the Trans-Canada Highway was completed across the province, giving travelers an alternative to the railway.

Moreover, the rail journey was slow. In 1898 the journey from St. John's to Port aux Basques took 28 hours. By the 1960s, despite the introduction of diesel engines and improvements to the track, the run still took 22 hours. The dining car was once considered to be one of the finest restaurants on the island, and there are many stories of travelers telling tales and singing songs long into the night. But by the 1960s the service had declined, and the time and expense of taking the train meant that other modes of transportation were becoming more attractive.

In 1968 CN introduced a Roadcruiser service, which took passengers across the island by bus in fourteen hours. Rail travel may have had a romantic appeal, but buses were now the mode of passenger transport preferred by both CN management and the traveling public. Less than a year later CN eliminated passenger trains altogether, with the exception of mixed trains on branch lines and the traditional May 24th weekend “Trouter's Special.” Freight was also facing increased competition from aviation and especially the trucking industry.

The railway could not compete. The track was narrow gauge (meaning the space between the rails was 3'6"), rather than the standard gauge (4'8½") of the Canadian railway system. Therefore, goods shipped by train had to be either moved to new freight cars in Port aux Basques or the cars had to have their wheels changed. Once loaded, it took longer to get the goods across the island, and the train could only deliver goods to stations and train yards. From there, freight had to be unloaded into trucks for final delivery. Trucks, on the other hand, could bring loads directly from Nova Scotia, cross the island faster, and deliver door-to-door. Business surveys in 1977-78 found that deliveries by rail took an average of twenty days, compared to six days for highway delivery. A businessman in St. John's around the same time claimed that he was receiving shipments from Moncton, N.B., in two days via truck, but in six to seven days via rail.

The Sullivan Commission

The result of increased competition from road and air meant that the railway, which had always struggled financially, was in a difficult situation by the 1970s. Levels of service were declining, and CN was losing a huge amount of money every year in Newfoundland – $23.5 million in 1976, for example. It was clear that the entire transportation system of the province, not just the railway, needed attention. In March 1977, the provincial and federal governments appointed a Commission of Inquiry into Newfoundland Transportation.

This became known as the Sullivan Commission after Chief Commissioner, Arthur M. Sullivan. The Commission held information meetings in over 120 communities in Newfoundland and in Labrador, and fifteen formal hearings at which 102 people and groups presented briefs. It released its report in two volumes, the first in July 1978 and the second in February 1979.

The Commission pulled no punches about the railway. “All of the available evidence indicates that … the railway cannot continue as a viable service,” the report read. “Therefore, it should now be planned to have a transportation network which does not include a railway in approximately ten years' time.” Recommendation 29 stated that “plans should be commenced now to phase out the railway.” Although Recommendation 30 provided for five years of renewed marketing and reorganization, after which the decision to abandon the line would be re-evaluated, it was clear that the Sullivan Commission did not have high hopes for the railway.

In general, the Commission blamed transportation problems on the lack of long-term, comprehensive planning, and based its recommendations around the idea that transportation services in Newfoundland and Labrador using air, road, or water should be integrated and mutually supportive. In its vision of transportation in the late 1990s, the railway was conspicuously absent.

Reaction and Response

Reaction to the report was predictable. People were fond of the railway despite its many problems, and did not like the idea of abandoning it. The provincial government of Frank Moores said in a press release that “Our railway should not be abandoned under any circumstances” and that “Any suggestion … that rail abandonment could produce trade-offs in terms of improvements in other parts of our transportation system is … unacceptable.” But this is exactly what would happen.

CN took the Commission's recommendation of a five-year plan to heart. In March 1979, CN announced that a Newfoundland Transportation Division had been formed. TerraTransport, as it was christened, was to operate under a five-year plan that would reduce the railway deficit to zero. This was attempted mainly by reducing the workforce and converting the freight service from rail cars to containers, which were interchangeable with trucks and could solve many of the problems caused by the narrow-gauge railway.

By 1982, the plan seemed to be showing results. Conversion to container transport and more competitive freight rates had gained back some lost business, and the railway deficit was coming down. But competition from other shippers and decisions taken by the Canadian Transportation Commission regarding freight rates affected TerraTransport, and it began to lose customers once again. In 1985 federal Minister of Transport Don Mazankowski suggested closing the railway in return for money to be spent upgrading the highway system.

Roads for Rails

The following year negotiations began regarding the amount of money that the province would receive in return for abandoning the railway. They were hastened by a bridge washout at Robinson's River in January 1986, which halted railway traffic for almost two months. The fact that CN diverted freight to trucks only helped prove that the railway was not necessary.

In its presentation to the Sullivan Commission ten years earlier, the provincial government had argued that CN, by moving passenger service to the highway through the Roadcruiser service, was effectively shirking its constitutional responsibilities. Under the Terms of Union, the federal government (through CN) was responsible for maintaining the railway. By moving the passenger service from the railway, for which the federal government was responsible, to the highway, which the province paid for, CN was making the province pay for a federal service.

This and other arguments played a part in the negotiations, and finally, on 20 June 1988, it was announced that the railway would be shut down. In what became known as the “Roads for Rails” deal, the federal government agreed to provide $800 million for highway improvements, and retirement and severance packages for railway employees.

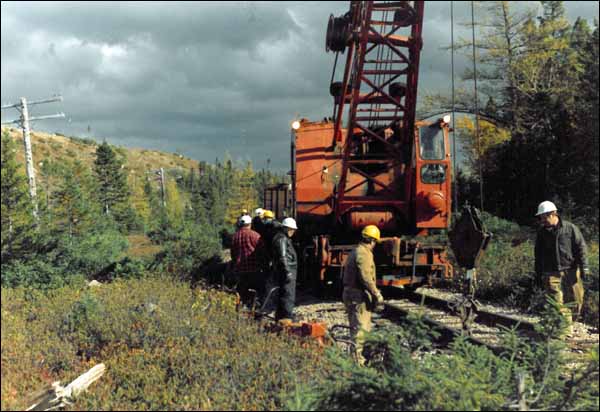

The last train ran on 30 September, 1988. CN wasted no time in tearing up the tracks. Less than a month later workers began removing the rails and ties from the road bed, and the last rails came up in November, 1990. The rails were sold for scrap iron, and the rolling stock was retired, scrapped, or sold off. Some of the engines were sold to railways in Nigeria and South America, but most were scrapped. A few were put on display.

Railway Heritage

The railway has long been recognized as an important part of the province's history and heritage. In 1997, the railway bed became the T'Railway, a recreational trail that forms the Newfoundland section of the Trans-Canada Trail, used by hikers, snowmobilers and many others. The T'Railway is also a provincial park, ensuring that it is preserved for future users as a reminder of the railway. Likewise, the old Riverhead railway station on Water Street in St. John's now houses the Railway Coastal Museum, which displays artifacts, photos, and documents about railway and coastal boat history. Several other railway stations have been preserved, as well as engines and cars. It is not unusual to see old freight cars used as backyard sheds, and railway ties and rails used as fences.

Retired railroaders have produced photographs, paintings, models, poems, and songs about the railway. Rising Tide Theatre's first production in January 1979 was the play "Daddy, What's a Train?", which dealt with the impending closure of the railway and the potential loss of heritage. The humourist Ray Guy has written several columns on the railway and its closure, and in 1995 Wade Kearley released The People's Road, a book about his trip, by foot, along the entire 547 miles of former railway track.

The time and expense that Newfoundlanders have put into preserving and remembering the railway indicates its cultural importance. Although it may be gone, the railway continues to play a role in Newfoundland's identity and heritage.