St. John's, 1815-2010

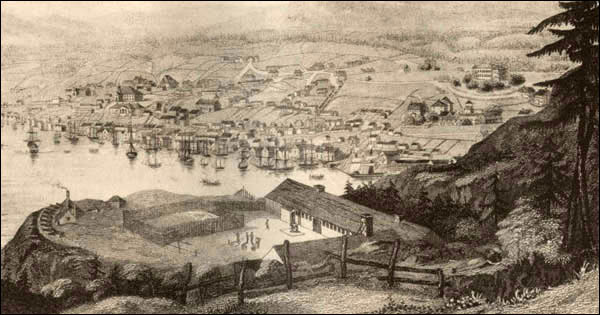

By the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, St. John's had grown into a substantial town of over 10,000 residents, and had become the colony's commercial and administrative centre. The fishing industry dominated Newfoundland's economy, and St. John's was the home of many merchants and businesses, in addition to being a vital port.

The town grew rapidly in the 19th century, with a substantially increased population, improved infrastructure such as roads and sewers, the development of fire brigades and a police force, and the establishment of the first municipal government in Newfoundland. This growth intensified in the 20th century, especially in the latter half, when major economic and political changes dramatically increased the city's population and importance.

In 1815 St. John's was the largest of several important political and economic towns in a British colony that was dependent upon the fishery and lacked any form of self-government. By 2010, St. John's had become the capital of a Canadian province, a social, economic, and political centre experiencing rapid growth and development in a post-fishery economy based largely upon offshore oil and service industries.

1815-1855

For most of the 19th century, St. John's was under the administrative control of the colonial government. Although many comparable North American cities, such as Saint John, Halifax, and Charlottetown had all achieved self-government by the 1850s, St. John's still lacked its own municipal council. A single-industry economy (the fishery), a large number of absentee landlords, and resistance to municipal taxation were the major factors behind this unusual situation.

Nevertheless, the town continued to grow in terms of population and services. There was some success in enacting fire regulations in the 1830s and after the 1846 fire, although disputes over taxes, lease lengths, and the responsibility for new building construction continued to be difficult to resolve. The government was able to provide the town with rudimentary police services, the first constables in St. John's being hired in 1812 and paid from the proceeds of tavern licenses. Their duties included nightly patrols, making sure taverns closed on time and preventing garbage from being thrown into the streets. The number of constables remained small into the 1840s, and the government depended upon the military garrison and the clergy to keep the public peace in times of crisis.

The first fire brigades appeared in the 1820s and were private and voluntary. In 1833 the new legislature passed the Fire Companies Act, which divided St. John's into four wards and assigned a fire brigade to each. Financial support for the brigades was compulsory for all householders and businesses. They were still underfunded and undermanned, however, and the military garrison remained crucial to fire control.

The ineffectiveness of these compulsory brigades was clear after the 1846 fire, and the Fire Companies Act was repealed. New voluntary fire brigades were established with ties to specific businesses and churches, for example the Phoenix Fire Brigade and the Cathedral Fire Brigade (supported by the Protestant and Roman Catholic communities, respectively) and the St. John's Water Company Fire Brigade (supported by the business of the same name). These arrangements allowed the new volunteer brigades somewhat better equipment, and they gained importance after the loss of the military garrison in 1870.

In 1877 the volunteer brigades were amalgamated under the name of the St. John's Voluntary Fire Brigade, and the St. John's Water Company and fire insurance companies were made financially responsible for its support. But the brigade remained underfunded and was unable to contain the 1892 fire. That catastrophe finally persuaded the government to institute a fire service with paid, full-time firefighters and modern equipment. Originally organized as a department of the Newfoundland Constabulary and cost-shared between the government and the municipal council, the St. John's Fire Department became independent in 1957.

1855-1888

Indicative of the continued growth of St. John's and its emergence as the colony's entrepôt, the government undertook efforts to develop the infrastructure in St. John's in the 1850s and 1860s. A major water service project which opened the Windsor Lake reservoir was completed in 1863 by the city council and the St. John's Water Company, and a Sewerage Act was passed the same year providing for the installation of sewers and drains. Colonial budgets for the 1860s included expenditures for roads, bridges, water, and sewerage for the town's population, which had reached about 25,000 by the 1870s. The police force had been slowly expanding in both size and duties since the 1840s, and was reorganized in 1870 when the military garrison left, becoming the Newfoundland Constabulary.

By 1888, further infrastructure developments were required, and in order to better manage the debt that would be incurred and the necessary taxation, the colonial government created the St. John's Municipal Council, which finally gave the town an elected body to manage its affairs. The Council was not an autonomous corporation, however, and was still largely under the control of the government. The Council's responsibilities were limited to water and sewerage, streets, fire service, and parks, and it would have a rocky existence for the next several decades.

1888-1934

The Municipal Council's limited powers were all too evident in the aftermath of the 1892 fire, when the colonial government took almost complete responsibility for reconstruction. The Council's power, and indeed its very existence was further threatened in 1898 when the government of Sir James Winter replaced it with an appointed commission in order to smooth the implementation of the new contract with R.G. Reid. The Council was restored in 1902, and St. John's elected a mayor for the first time, although the Council remained indebted and in many ways subservient to the colonial government. Though the Council's financial situation began to improve, a commission once again replaced the Council in 1914, with a mandate to improve operations and finances, and recommend a future system of municipal government. Political and legal wrangling, complicated by World War I, eventually led to the passing of a Municipal Act in 1921, which finally recognized St. John's as a "city," but stopped short of full incorporation. The 1921 Municipal Act and its many subsequent amendments remain the basis of the City Council's authority, although St. John's still lacks the level of autonomy often seen in North American cities.

The city continued to grow and develop services and businesses, including an increased manufacturing sector and business related to the railway and the dry dock. Gas lighting, in place since 1854, was supplemented and eventually replaced by electricity, and the St. John's Street Railway began operation in 1900. Although the Depression hit St. John's hard and the city continued to struggle financially and politically, the population continued to grow as people moved from the outports to the city in search of work or relief, reaching nearly 40,000 by 1935.

1934-1949

From the establishment of the Commission of Government in 1934 until Confederation in 1949, the St. John's Municipal Council was the only elected representative government in Newfoundland (the National Convention was elected in 1946 but was not a law-making body). The city faced serious economic and social challenges during the Great Depression, and also had to deal with the impact of the Second World War.

During the war, St. John's became crowded with Canadian, American, and to a lesser extent British servicemen, as the harbour became a base for naval convoy escorts. Major Canadian and American military bases were established, notably the Royal Canadian Navy barracks, Fort Pepperrell, and the Torbay airfield. The war spurred major development in the city and the influx of money had large economic benefits. Many people continued to move to St. John's from the outport communities in search of work on the bases, and the city's population reached almost 45,000 by 1945.

St. John's had had a recognized housing problem, especially in the central slum area, since the early 1900s. Attempts to improve the situation finally saw some success in the late 1940s. The Commission of Government supported the Municipal Council in the creation of Churchill Park, the city's first garden suburb and the first successful attempt at creating new housing. Although Churchill Park did little to improve the downtown slum, it did begin a period of housing improvement which eventually cleared the slum, and in the process encouraged the expansion of the city beyond the downtown core.

1949-2010

With Confederation came major changes. The city was able to call on major resources from the provincial and federal governments for the first time, and was finally able to provide publicly subsidized housing and clear the central slum by the 1960s. The city's rapidly expanding population and the increase in the use of cars and trucks allowed the city to expand at a much greater rate than before. It quickly grew beyond its downtown boundaries to encompass much of the surrounding area. Neighboring communities also grew, becoming commuter towns feeding into St. John's, which was developing into the predominant regional and provincial service centre.

While problems with the cod fishery caused major economic difficulties in the late 20th century for Newfoundland and Labrador, including St. John's, by the time of the 1992 cod moratorium the city was already a service and supply centre for the burgeoning offshore oil industry. The oil boom has been advantageous to Newfoundland and Labrador as a whole, but it has been particularly beneficial to St. John's and the surrounding area, where in 2011 unemployment is low and property values and rental rates are high and increasing.

Although its status as a service and administration centre for the fishing industry has long been overshadowed by more general administrative and governmental roles, the city of St. John's remains an important maritime service centre. It is the centre of government for the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as the island's major service centre for health care, large corporations (especially the oil industry), and government. In two centuries the population has grown from 10,000 people living very close to the harbour to a St. John's Census Metropolitan Area population of over 200,000 people spread over 400km2. With a bright economic future based on the oil industry (at least in the short term) and continuing urbanization, St. John's will continue to be a growing city.

For more detailed analyses of municipal politics and policy in St. John's in the 19th and 20th centuries, see Dr. Melvin Baker's Homepage.