Company Towns

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the foundation of new communities that were based upon the burgeoning industrial development of the resources of Newfoundland and Labrador. Although manufacturing in St. John's, for example, contributed much to the economy, this article focuses upon towns which were based exclusively upon one industry. Since there are too many such towns to discuss all of them here, we can examine two of them, Buchans and Grand Falls-Windsor. These towns grew up near a mine and a paper mill respectively, and can illustrate some of the characteristics of company towns.

In most respects, these industrial towns are like their counterparts elsewhere in North America. They differed from outports in that their population was larger, and the origins of their residents more diverse. Industrial workers and their families came not only from Newfoundland and Labrador, but from many countries. They were paid an hourly wage and did not operate on the credit system. Average incomes in these industries were also higher than in the fishery, and conditions in the mines and mills led to working-class solidarity and the growth of trade unions. It is important to understand that these communities were "company towns", in which the company had a significant control over the lives of families.

Mining Communities

The first industrial towns were mining communities, such as Tilt Cove, Notre Dame Bay, which started in 1864 and reached 768 residents five years later. Although the mineral potential of Newfoundland and Labrador had been noted by the first explorers, and attempts to open mines had been made, no mining communities existed until the 19th century. Such mining towns were usually remote from other communities, which made it easy for the company to dominate the lives of its employees and their families. In Betts Cove, a mining community consisting of 2000 residents, with poor quality housing and few amenities, the miners were paid an hourly wage, but in company "scrip" which could only be spent in the company-owned store.

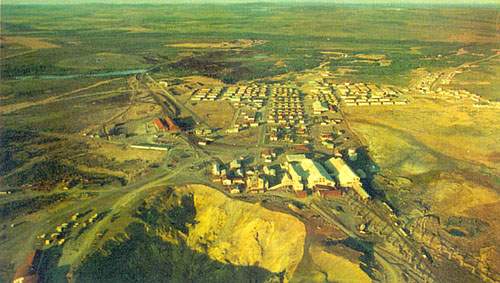

Several of the mining towns that were established during the 20th century, such as Wabana (Bell Island), Buchans, Wabush, and Labrador City, had higher standards of living and were more like urban centres elsewhere. Yet mining towns in the interior could be even more oppressive than those on the coast. The company-owned railroad provided the only way in and out of Buchans during its first few decades. Privately-built homes were not allowed, and employees had to live in poor-quality company-owned houses or bunk houses. Sometimes people in industrial towns were satisfied with the company dominating their lives as long as they continued to enjoy a higher standard of living than families in the outports. In other towns people resisted the company and fought to gain control over their towns. When a road out of Buchans was completed in 1956, about 60 families rebelled against the company's domination of their lives and built their own homes on land that the company did not own across the river. They named their renegade settlement "Pigeon Inlet" after a fictional outport on a popular Newfoundland radio program. Later, families established a privately-owned "townsite" to escape the control of the company. The townsite was amalgamated with the company-owned town in 1979, not long before the mine, the community's largest employer, closed.

Paper-mill Town of Grand Falls

The paper-mill town of Grand Falls, established in 1906, provides another example of the character of industrial towns. For much of its early history, like the mining communities, it was a "company town." Families lived in houses provided by the company and people were not able to live in the town unless they worked in the mill or had permission from the company. A separate community, Grand Falls Station, grew on the opposite side of the railway track to the mill property, as a place for non-mill workers and their families to live. Those who did not work for the company, or worked for the company outside of the mill, such as loggers, who provided the raw material to be processed, were not only prohibited from living in the town but also excluded from socializing with mill workers. Social life within Grand Falls, such as participation in sporting teams, as organised on the basis of one's employment in the mill. So there was little "community" feeling between the residents on the two sides of the railway tracks.

Grand Falls Station grew into a large community with many residents and businesses, but since the company did not provide services such as water and sewer, it had poor sanitation and living conditions. In 1938 a local citizens' committee succeeded in incorporating the "wrong side of the tracks" as the municipality of Windsor, making it the first community outside St. John's to be incorporated. Eventually, the paper company relinquished control over the Grand Falls, but social distinctions between the two towns were slow to erode. They amalgamated into one municipality in 1991.

Sawmill City of Corner Brook

Newfoundland's second city, Corner Brook, started as an industrial town as well. The site of a sawmill since 1864, it remained a small town until 1926 when British industrialists built a pulp and paper mill. As was the case with Grand Falls, the company provided mill management and skilled workers with housing near the mill on attractive real estate, and others built accommodations on the nearby hill sides.

Labour Relations

Industries such as mining and papermaking are capital intensive, and employ few labourers compared to the more labour intensive fishery. Papermaking companies, for example, were able to pay relatively high wages to their highly-skilled employees. Wages in the industrial communities were higher than the Newfoundland and Labrador average, and many of these communities had electric power and other social amenities before they were available in many fishing outports. The relative affluence of residents, labour requirements of the industry and larger size of the town, allowed these industrial communities to have a large middle-class of professionals and managers. Since many of these professionals and highly-skilled technical staff came from other countries, people in these "oases of prosperity based on foreign capital," as one observer referred to them in the 1930s, had a similar lifestyle to industrial towns in the rest of North America.

With the urban lifestyle and industrial capitalist organization of the labour force, came the same sort of labour relations that existed elsewhere. The experience of working underground, and the poor treatment handed out to miners by the companies, gave miners and their families a particularly strong sense of antagonism toward the company. Miners organized unions and were willing to strike for better working conditions and higher pay. This was difficult, since companies were often able to prevent union organizers from visiting the town, for example. Paper mill workers were often unionized as well, although the relatively higher wages and much safer working conditions made them less militant than miners. Although there was solidarity among mill workers, one effect of the division of mill workers and "outside" workers into two "communities" (Grand Falls and Windsor) was to make it possible for the company to avoid mill employees siding with those who worked in the woods during periods of labour strife. During the 1959 International Woodworkers of America strike, for example, many mill employees sympathized with the company rather than striking woods workers.

Ore bodies are eventually exhausted, and mining communities were either abandoned after the mine closed as was the case in Tilt Cove, or in a few cases such as Wabana and Buchans residents found other sources of employment. Even then, these towns are a shadow of their former size and much less prosperous. Technological change can lead to large-scale downsizing of the labour force even when the mine continues to produce ore, as is the case in Wabush and Labrador City, or paper, as in Grand Falls and Corner Brook. The residents of these communities have worked hard to maintain services in the face of a shrinking tax base.

Health and Education Services

After 1949 the federal and provincial governments both took a larger role in providing services such as health and education to all communities, allowing the companies in industrial towns to back out of providing many services. These two levels of government also supported the creation of municipal councils. The people of many communities took democratic control over their towns. The "company" still "owns" a few towns and provides for many of the needs of citizens, such as Churchill Falls, Labrador, the site of a hydroelectric generating station. But such situations are now rare and confined to places where isolation makes the community unattractive in which to live unless the company subsides housing and amenities. The industrial towns of Newfoundland and Labrador are now largely indistinguishable from urban centres elsewhere in North America.