Women's Suffrage

Women in Newfoundland won the right to vote and run for public office in April 1925 after decades of lobbying government officials and promoting their cause on the public stage. As voting members of society, women became better-equipped to influence public policy and advance their concerns, which often included domestic violence, maternal health, child welfare, and public education. Although suffragists endured years of mockery and opposition while fighting for enfranchisement, their victory affirmed the status of women as equal members of society and challenged traditional gender roles.

The 1890s

The first campaign for women's suffrage in Newfoundland took place in the 1890s and was closely linked to a growing prohibition movement. During this period, some of the country's women, particularly those in larger centres, argued alcohol consumption led to increased rates of domestic violence, poverty, and other social problems. A group of about 60 St. John's women formed the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in September 1890 to promote these concerns, arguing that women and children were the least likely to drink, yet the primary victims of social problems caused by alcoholism. Women were physically weaker than men, financially dependent on their husbands and fathers, and lacking any political power to control their lives.

The WCTU believed that if women had the right to vote in municipal elections, they would be able to reform lax liquor laws and improve their social circumstances. The group marched from the Old Temperance Hall (today the LSPU Hall) in downtown St. John's to the Colonial Building on 18 March 1891 to present government officials with petitions supporting their cause. These demands were controversial at the time – they not only advocated expanding women's roles into electoral politics, but also attempted to restrict male behaviour.

The legislature debated enfranchising women on 15 March 1892 and ultimately defeated the motion in a vote of thirteen to ten. The WCTU continued to advocate women's municipal suffrage in the coming year, but encountered much opposition from the press and some government officials. The Evening Telegram, for example, published an article on 20 April 1893 announcing “we have no word of sympathy or encouragement for those ladies who would voluntarily unsex themselves, and, for the sake of obtaining a little temporary notoriety, plunge into the troubled waters of party politics.”

The House of Assembly raised the issue again on 4 May 1893, but rejected it for a second time by a vote of 17 to 14. Defeated, the WCTU decided to focus its energies on charitable and missionary work rather than pursue women's suffrage any further. The topic, however, did not entirely disappear from the public consciousness. As countries around the world granted women the vote in the coming years – including New Zealand (1893), Australia (1902), Great Britain (1918), Canada (1918), and the United States (1920) – various Newfoundland clubs and societies held debates and lectures on women's suffrage.

Ladies' Reading Room

Foremost among these was the Ladies' Reading Room and its associated Current Events Club, which a group of prominent St. John's women formed in December 1909 after a fraternal society banned them from its suffrage debates. Although most of the club's founding members belonged to the city's elite, the Reading Room's $3 membership fee made it accessible to women from all classes; within a few weeks of opening, the establishment recruited 125 members. While at the club, women could read international newspapers and magazines, debate current affairs, and attend or deliver lectures. As suffragist scholar Margot Duley points out, the club acted as an informal university that helped politicize a generation of influential women and give them valuable experience in debating and public speaking.

Although not an overtly suffragist organization, the Reading Room and Current Events Club often discussed women's enfranchisement and many of its members converted to the cause as a result of their exposure to suffragist literature and discussions. Many believed the general public undervalued women's contributions to society – both as homemakers and as teachers, nurses, and other professionals – and that until women obtained political representation, they would remain among the most vulnerable members of society.

It was apparent to many suffragists, however, that their message was not a popular one. As suffragist campaigns unfolded elsewhere in the British Empire, they often resulted in much civil unrest and disobedience. Many Newfoundland newspapers portrayed these events in a negative light and suggested suffragists were irrational and dangerous. This in turn helped to shift public opinion against women's enfranchisement. Local suffragists realized that if their cause was to be a success, they would have to make their message palatable to the general public and conform as much as possible to social conventions.

World War One

Although the First World War delayed the suffrage movement, it also provided many women with a powerful argument for their right to vote. Thousands of women from Newfoundland made substantial contributions to the war effort by working as nurses, raising money, and knitting socks, sweaters, scarves, and other clothing for troops overseas. Most volunteers joined the Women's Patriotic Association (WPA), which formed in 1914 to support enlistees and their dependants at home. Unlike in Canada and the United States – where women often contributed to the war effort by joining the industrial workforce – the WPA promoted what was widely considered traditional women's work: knitting clothes, nurturing the ill or wounded, and raising money for charity.

By the end of the war, the WPA contributed more than $500,000 – worth about $6.5 million today – to the war effort and was lauded by government officials, the press, and public. Its efforts made apparent the tremendous social and economic importance of women's traditional work, which suffragists used as a compelling argument for the vote during peacetime.

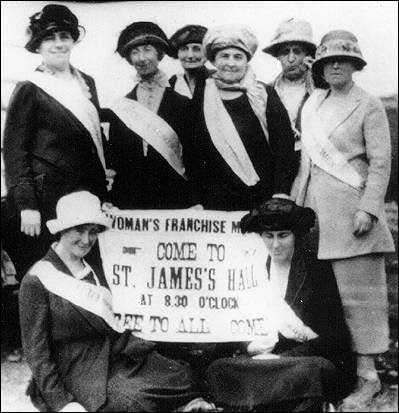

They formed the Women's Franchise League in 1920 and launched a publicity campaign to promote their cause. League members wrote letters to the editor, canvassed houses and businesses, and screened advertisements at local movie houses. They also circulated a petition throughout the country to garner support. By emphasising the importance of traditional women's work, the league effectively diffused any opposition that enfranchisement would prompt women to abandon the domestic sphere and undermine the family unit. Suffragists argued that female voters would advocate for better health-care, education, sewerage, and other social services, and reminded the public that Newfoundland was one of the last members of the British Empire to refuse women the vote.

Although many of the country's newspapers supported women's suffrage by the 1920s, the league still encountered much resistance from government officials, particularly Liberal Prime Minister Sir Richard Squires. When the legislature debated a franchise bill in 1921, the government easily defeated it by a vote of 13 Liberals against nine Conservatives. The league did achieve a degree of success that year when St. John's granted the municipal vote to women who owned property within the city. Many women, however, were still excluded from voting as it was often their fathers and husbands who officially owned land. The next municipal election took place in 1925, and although three women ran for office – May Kennedy, Fannie McNeil, and Julia Salter Earle – none was elected.

League of Women Voters

Following their 1921 defeat at the Newfoundland legislature, league members spent the next few years accumulating support for their petition and by 1925 had gathered 20,000 signatures. By then, charges of corruption had driven Squires from office and Walter S. Monroe was the country's new prime minister. Aware that Monroe and some of his cabinet were sympathetic to the suffragist cause, league members once again lobbied government officials for support. Monroe introduced a franchise bill to the legislature in 1925, where it passed unanimously on 9 March and became law on 3 April.

Although the law stipulated women could only become voters at age 25, while men could vote at 21, league members were satisfied with the new legislation. They held a victory banquet on 21 April, where the group changed its name to the League of Women Voters, a non-partisan organization that promoted compulsory education, child welfare, maternal health care, and other social issues.

On 29 October 1928, 52,343 Newfoundland women cast ballots in their first general election – representing a 90 per cent voter turnout rate. Lady Helena Squires became the first woman to sit in the country's House of Assembly after winning a by-election in 1930. Four years later, however, Newfoundland voluntarily suspended its right to self-government and swore in the Commission of Government. When the country returned to the polls in 1946 to elect a National Convention, all Newfoundland people aged 21 and older were eligible to vote.