The Resettlement Program

"Resettlement Now While Resettlement Pays"

Outport People

Simani

1986

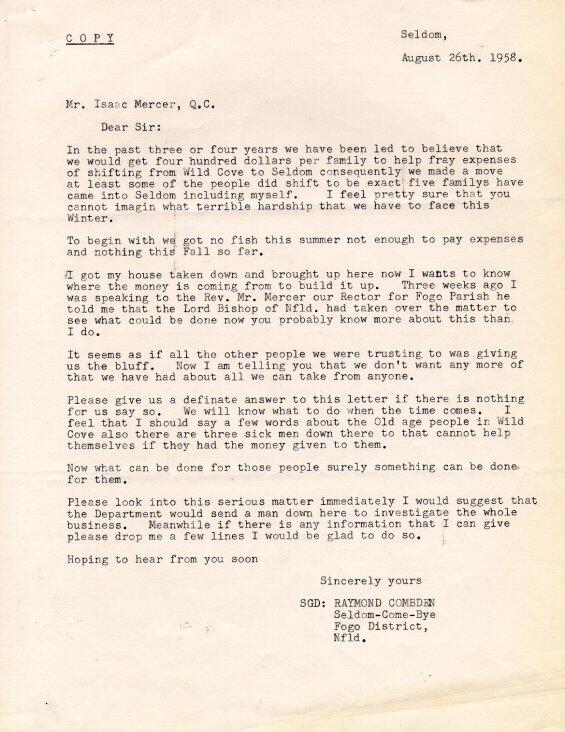

With a new fresh-frozen industry replacing the salt-cod fishery in Newfoundland, the issue of resettlement became very much tied to the modernization of the industry. In 1965 a five-year federal-provincial partnership was established, and the Centralization Programme, previously delivered by the provincial Department of Welfare, was replaced by a Fisheries Household Resettlement Programme. This programme was administered by the Department of Fisheries at both levels of government. Decisions were ultimately made by the Household Resettlement Committee made up of ten provincial and five federal government officials. In 1967 the programme was turned over to the newly-created provincial Department of Community and Social Development, but remained federally with Fisheries.

The Growth Pole Theory

The "resettlement plan" differed from Centralization, and was based on the growth pole theory, rooted in the work of the 17th century English economist, William Petty. The theory assumes that development in a specific area will generate further spin-off industries, and people will move there. The new plan therefore encouraged rural Newfoundlanders to move to designated "growth centres", rather than to places thought not to be economically viable, as had been the case under Centralization. Three categories of "receiving centres" were created: major fisheries growth centres, approved fisheries resettlement centres, and other approved receiving locations.

The Resettlement Process

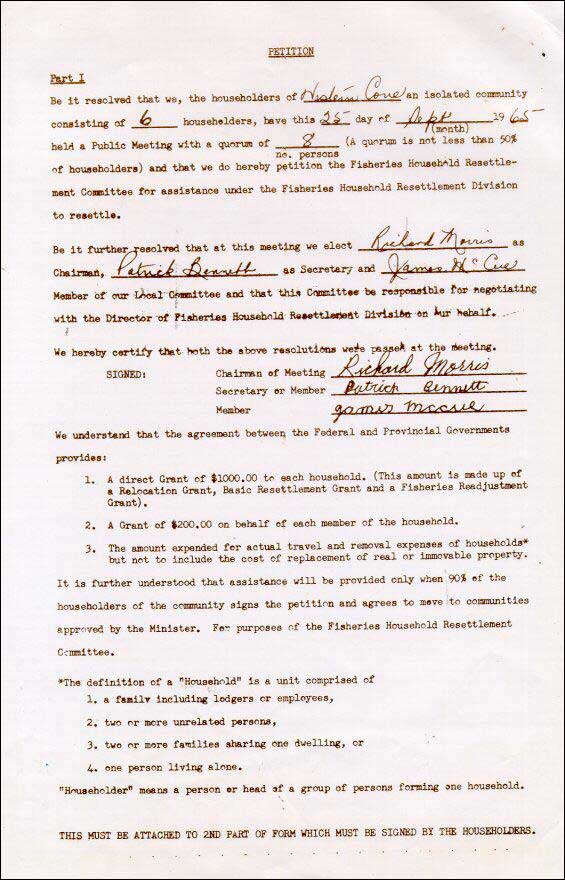

The regulations pursuant to the Resettlement Act of 1965 stated that as a first step, there had to be a public meeting attended by at least 50 percent of all householders in a community considering resettlement. This meeting would pass a resolution stating that the community desired resettlement. A three-person committee would then be chosen to represent the community and conduct negotiations with the provincial Department of Fisheries (Community and Social Development after 1967). The committee then had to circulate a petition in the community supporting resettlement. This required no less than 90 percent (by 1967 80 percent) of householders' signatures, and had to include the chosen relocation community. A justice of the peace verified that the petition contained the number of signatures required.

A "householder" was defined as the head of a group of persons forming one household. This group could include family, lodgers, employees, two or more unrelated persons, two or more families sharing one dwelling, or one person living alone. The term "household" also included personal possessions inside the house, or any items on the premises used for work purposes. If a householder was absent when the petition was circulated, he or she was informed by the committee upon their return. If the householder supported resettlement, it was his or her obligation to inform the committee by a letter, which the committee then attached to the petition. Interestingly, the petition could be signed by the spouse of an absent householder. Any householder who did not sign the original petition, but left when the rest of the community moved, could also qualify for assistance under the same conditions, providing he or she moved to an approved community.

The community committee forwarded the completed petition to the Director of the Household Resettlement Programme. If the petition was approved, each householder completed an application form as outlined by the Department of Fisheries. The sum of $1,000 was paid to the head of each household to help defray the cost of moving the dwelling and other buildings. If the householder did not physically move any buildings, the same amount was paid for the disruption involved in moving, and to enable the householder to relocate elsewhere. The sum of $200 was paid for each member of the household. Receipts could be submitted for travel, and for the removal expenses of personal effects, fishing gear, boats, and livestock. It was quite common for resettlers to use grant money to float their homes to new communities. For example, the local merchant in Spencer's Cove, Placentia Bay had a vessel built in the early 1960s to tow dwellings for residents. Mr. Samuel Williams of Tack's Beach, also in Placentia Bay, used his own vessel to float homes fifteen miles across the bay to Arnold's Cove. Some old resettlement photographs show the vessel Goose Lake, removing dwellings for resettlers as late as 1969.

Payments were only made to those householders living in communities which received approval for assistance from the Fisheries Household Resettlement Committee (FHRC), as stipulated by the 1965 agreement. Before receiving any money, householders had to move to designated growth points or other approved areas within the province, properly complete their application, and submit their travel and removal expenses as specified in the regulations.

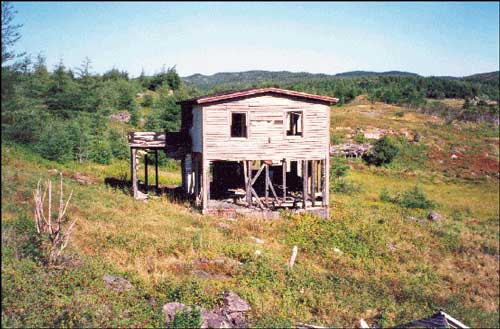

The provincial government could order the removal of buildings left in an evacuated community, if it was possible there would be an attempt to return there. The regulations clearly stated that no person could return to an evacuated community and occupy property or construct new buildings there, without permission.

Problems

There were significant problems. Three groups had the most difficulty: the elderly, widows, and large family households. The biggest issue was the availability of affordable housing. For many it was a double loss. Houses in the communities left behind were worthless, and even with relocation assistance, few could afford to buy or build new homes elsewhere. The elderly, with little chance of earning a living, could not afford to start again. Widows were in much the same position, especially those with young children. Families with large numbers of children could not afford to build houses suitable to their needs, and there were few homes available that could accommodate large families. The government later provided supplementary allowances up to $3,000 to help solve the problem.

The sociologist Ralph Matthews noted that it was difficult to determine just who benefited from resettlement. In their home communities, many families had grown their own vegetables and raised livestock. They now had to buy the food which they had once produced themselves. As whole communities evacuated, merchants may have also suffered significant losses by leaving behind shops, stores, and wharves. An economic cost-benefit study completed in the late 1960s indicated that it would take over twenty years for the average householder to replace what had been lost financially, assuming he or she was steadily employed. Undoubtedly, resettled families gained much in the social sense; there were better educational opportunities for children, easier access to healthcare, and all the benefits of modern infrastructure. But growth centres did not fulfill the employment expectations as suggested by the growth pole theory. Since 1977 the provincial unemployment rate has remained stubbornly high.

Resettlement was one aspect of the government's plans to diversify and modernize the Newfoundland economy. But the abandonment of outport communities did not bring the province any closer to being a self-supporting market economy. Some growth centres became overcrowded from the employment perspective, creating disadvantages for the work force and causing temporary strains on the education system. Long-time residents of receiving communities sometimes resented the resettlers moving into their communities, particularly those of different religious backgrounds. Ultimately, neither the government nor the people involved were well prepared to cope with the full effects of resettlement. As a result, it was a traumatic experience for many, and has created a feeling of bitterness that is still echoed today.

From the government's point of view, though, the resettlement programme was a success, much more so than Centralization. Between 1965 and 1970, 3,242 households, totaling 16,114 people from 119 communities were resettled. The cost to the federal government was $5,011,582; the cost to the Government of Newfoundland, $2,428,198. This represents an average cost of $2295 per household or $462 per head. The equivalent today (2017) would be $14,684 per household and $2,956 per head, for a total programme cost of $47,600,000 . Although the federal and provincial government renewed their partnership in 1970 and committed to another five-year resettlement plan, support for resettlement died away after J.R. Smallwood's Liberals lost the 1971 provincial election to the Conservatives led by Frank Moores.