Naval Government 1729-1815

The traditional view of 18th-century Newfoundland is that the island was no more than a great ship moored off the Grand Banks, a seasonal fishing station without the basic rudiments of civil society. Naval government remains in the shadow of 19th-century reformers such as William Carson and Patrick Morris, both of whom portrayed it as inherently weak and inevitably arbitrary. The judiciary is still viewed in terms of imperial policies that restricted formal institutions: local customs were, it is assumed, woefully inadequate stand-ins for the panoply of English law.

However, compared with other 18th-century regimes, the legal system that governed Newfoundland prior to 1815 was relatively stable and effective. Beneath the veneer of official British policy, which defined Newfoundland solely as a seasonal fishing station, the island developed a customary system of governance that met the needs of those in power. Naval and civil magistrates successfully exercised legal authority, and merchants became actively involved in government when their interests were threatened. Before the advent of an independent press, local officials and magistrates were not subjected to critical public evaluation. Despite statutory reforms in 1791-92, the basic mode of governance did not change significantly until the 1810s. Without a local legislature or a bourgeois public sphere, naval governors were relatively free to act as they saw fit.

As in most other colonial societies, law and government in Newfoundland were essentially reactive, limited by available resources, and shaped by individual initiative. After 1729 the primary legal resources consisted of the naval governor (who served concurrently as the commodore of the Newfoundland station); his junior officers (who acted as surrogates); the magistrates in each district (most importantly the justices of the peace); and the fish merchants who dominated St. John's and the outports. Although the fishing admirals contested the authority of the governor and magistrates in the 1730s, by the 1750s they were no longer an independent force. In the second half of the 18th century the fishing admirals became co-opted by the island's government.

As in the 17th century, Newfoundland had a form of dual authority, but it was a cooperative system of naval and civil officials. By the mid-1760s the island was divided into nine districts, administered by civil magistrates, and five maritime zones, governed by naval surrogates. At the lower level, justices of the peace took depositions, held petty sessions, and organized quarter sessions. Each year the governor appointed several naval commanders to act as surrogate judges, ordered to the various bays to settle disputes and to preside over autumn quarter sessions–termed a surrogate court–usually with the local justices of the peace.

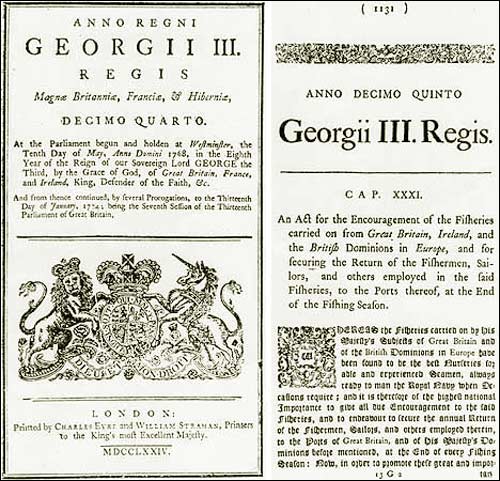

The most important theme in the history of law and government in this period is the process by which the island's institutions adapted to local conditions. Five courts dominated the administration of law: the court of court of oyer and terminer (established in 1750), which heard serious criminal offences; the governor's court in St. John's (convened from 1749 to 1780); the surrogate courts (established in 1749 and reconstituted in 1792); the sessions held by justices of the peace (established in 1729); and the vice-admiralty court at St. John's (convened sporadically since 1736). Each of these institutions evolved beyond its formal jurisdiction. For example, while naval officers were authorized by statute only to act as appeal judges, in practice they judged a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. The surrogate courts were based on customary law, in other words, the practices which had grown over the years to be recognized as legitimate authority. Such customary practices were, in fact, an accepted part of the English common law tradition. When the British parliament passed a new act for the Newfoundland fishery in 1775, known as Palliser's Act, it merely codified existing customary laws.

From 1788 to 1791 the legal system in Newfoundland experienced a crisis. An appeal heard in England against a decision by a surrogate judge threw the island's judiciary into temporary confusion. Cases piled up by the hundreds while authorities tried to decide how best to reform the courts. In 1789 this crisis deepened further when a shipload of Irish convicts was landed at Bay Bulls and Petty Harbour. Admiral Mark Milbanke, who had just been appointed governor, had to overhaul the judiciary at the same time as dealing with the dangers posed by the convicts. Faced with these problems, the British government conducted an investigation into law and government in Newfoundland.

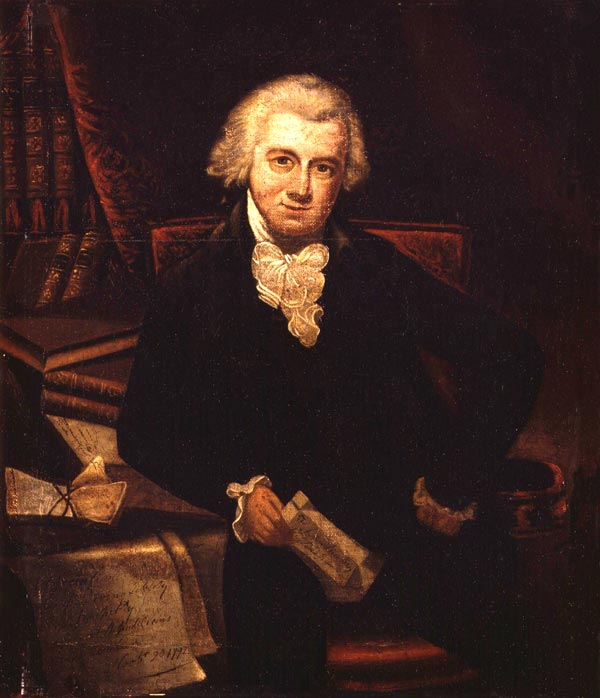

When legislation was passed in 1791, it provided only for a temporary court of civil jurisdiction. The Judicature Act was limited to one year, during which John Reeves, the newly-appointed Chief Judge, would assess the requirements of the administration of law in Newfoundland. In October 1791 Reeves prepared his first report on Newfoundland's legal system in which he sketched plans for a new judiciary. He recommended that the government establish a type of legislative council in Newfoundland. In his second report, however, he abandoned this concept in favour of more pragmatic measures. After visiting the outports in 1792, he affirmed, "I am convinced, from what I there saw, that there is less need of regulations than of persons to execute them; and that instead of making new laws, we should first find a new set of magistrates to execute the old ones" (quoted in Bannister 1999). In the wake of the crises of 1788-89 the naval officers had withdrawn from their customary position as sole surrogate judges. Civilians began to fill the surrogate bench after 1791, but the governor and his junior officers continued to dominate the courts.

Chief Justice Reeves' recommendations formed the basis of Newfoundland's constitution for the next 30 years. In 1792 a second Judicature Act created a supreme court for both civil and criminal jurisdiction, and entrenched legally the system of surrogate courts that had long operated customarily. Again the act was for one year only and had to be renewed annually until 1809. The British government was trying to close the gap between imperial policy and local practice, but it did so by tailoring law to available legal resources. Far from being seen as an aberration, this preference for local customs conformed to the English common law tradition. Existing institutions, such as the surrogate courts, were favoured over innovations, in particular the short-lived court of common pleas.

The reforms of 1791-92 were not simply rungs in a ladder of legal progress. From the 1730s to the 1810s the governor, magistrates, and merchants constituted a de facto legislature and executive to approve and enforce local policies. This arrangement was limited to specific projects, such as building of court houses and other public works, or defraying the cost of criminal trials. From London's perspective, government and the courts in Newfoundland functioned relatively well, cost comparatively little, and caused few political problems. Britain's policy toward the island was not wholly neglectful, nor was it inherently repressive or particularly enlightened; rather, it followed the path of least resistance until forced to legislate the minimum changes required for a functional judiciary. An act passed in 1811 bestowed limited property rights, though this and other minor reforms did not significantly alter the island's basic system of government. However, during the Napoleonic Wars the island experienced massive social and economic changes, and after 1815 a local reform movement emerged to pressure the British government to grant Newfoundland its own elected assembly.