Megaprojects

Following his failed attempt to establish a broad range of small industries in Newfoundland and Labrador during the 1950s, Premier J.R. Smallwood turned his attention to a handful of large-scale industrial projects during the 1960s – a linerboard mill in Stephenville, an oil refinery in Come By Chance, and a phosphorus manufacturing plant in Long Harbour. Smallwood hoped that by industrializing the province, he would provide jobs for future generations and generate enough revenue to modernize the struggling fishery.

An early stumbling block, however, was money. Although Confederation had left Newfoundland and Labrador with a $45 million surplus, the province could not afford to finance major industrial developments alone, as it was also spending large sums of money on roads, communications, education, and other services. Consequently, Smallwood solicited help from foreign developers by offering them a variety of enticements, including tax concessions, government loans, and cheap hydroelectric power.

Criticism from the press, public, and other politicians claimed Smallwood was working for the benefit of an elite upper class rather than for the province. But the premier defended himself: "Surely every Newfoundlander knows in his heart," he wrote in 1969, "that I have tried to develop Newfoundland for the people of Newfoundland … If a Lord Northcliffe, a Sir Eric Bowater, a John C. Doyle, a Henry Ford, a John D. Rockefeller, a John M. Shaheen starts up an industry that gives jobs to thousands, should a Government, a President, a Premier be condemned because industries are started by rich men who want to become richer?"

In the end, all three megaprojects cost taxpayers a great deal of money, but failed to produce satisfactory results. Of the three, only the oil refinery in Come By Chance is still operating.

Stephenville

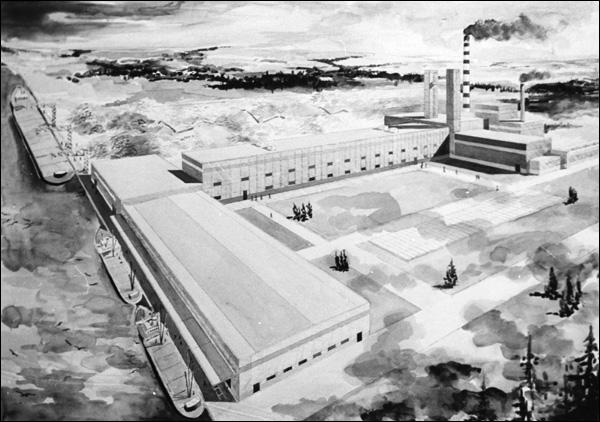

In 1966, the American military closed its air base at Stephenville, leaving hundreds of local men and women out of work. Determined to create jobs for them, Smallwood arranged with American businessman John C. Doyle to build a linerboard (cardboard) mill there. The two agreed that loggers would harvest wood for the operation in Labrador, because pulp and paper companies in Grand Falls and Corner Brook already held rights to much of the island's forests. As a result, Smallwood hoped the project would not only create jobs in Stephenville, but in Labrador as well.

Doyle formed Labrador Linerboard Limited to build the mill, and in return received large government subsidies. Although the province originally intended to spend only $54 million on the project, its investment had ballooned to $300 million by the time the mill stopped operating in 1977.

Several factors contributed to the closure – competing mills in the United States were producing a cheaper product, Stephenville was far away from its European markets, and the mill had to pay out millions of dollars a year to employ its 1,600 workers. Most troublesome, however, was the distance between the mill and its supplier – the cost of shipping wood from Labrador to Stephenville drove up the price of the final product.

A year after the mill closed, the province sold it to Abitibi Paper Company for $43.5 million. Following 18 months of renovation, the facility reopened in 1981 as a newsprint mill. It closed again in 2005, putting approximately 300 people out of work.

Come By Chance

Smallwood's partnership with a second American industrialist to build an oil refinery at Come By Chance again produced disastrous results and plunged the province into deeper debt. Like Doyle, John Shaheen received millions of dollars in government loans to build and promote the facility, but failed to make the endeavour a profitable one.

As soon at the refinery opened in 1973, it began losing money. Faulty equipment and labour disputes decreased production, competing refineries in Eastern Canada hurt business, and the price of crude oil spiked in the 1970s, forcing the refinery to pay suppliers more than it had originally anticipated.

Three years after it opened, the refinery declared bankruptcy. Hundreds of men and women were out of work, and taxpayers had spent approximately $42 million on the failed project. The facility was idle for 11 years before Bermuda-based Newfoundland Energy Limited reopened it in 1987. The refinery has been operational ever since, and boasted exports in excess of $2 billion in 2007. In 2014, the refinery was sold to North Atlantic Refinery Limited, but less than three years later the company was reportedly looking to sell the plant due to higher production costs than its competitors.

Long Harbour

Smallwood's promise of cheap power from the Bay d'Espoir project attracted the phosphorus manufacturer Electric Reduction Company of Canada Industries Limited (ERCO) to Long Harbour in the 1960s. The province also gave ERCO a $15 million bond issue to help build its phosphorus plant.

Like the Come By Chance refinery, however, returns on government investment were small and the plant encountered difficulties as soon as it opened. Chief among these were health and environmental problems – ERCO released untreated waste into Placentia Bay, which killed herring, cod, and other fish; fluoride emissions damaged local vegetation; and deformed moose and hares turned up in the area (scientists later found high levels of fluoride in some of the animals' bones). ERCO took steps to correct these problems, but at great financial cost.

In 1989, the company closed the plant, leaving 290 people out of work. In the following years, the town's population dropped by more than half to about 350.

'Prepared to Gamble'

In its 1967 report, a provincial Royal Commission on the economy advised the government to exercise more caution in its negotiations with foreign businesses and developers: "Efforts by Government to attract new industries into the Province should be far more rationally and systematically organized than hitherto … It is suggested that, where some assistance is indeed justifiable, it should be given in the form of measurable grants (a more controllable form of aid) rather than in the form of concessions and subsidization of inputs such as power."

Smallwood, however, defended his decision to make government loans and cheap power available to foreign industrialists in his 1969 publication, To You with Affection from Joey. Newfoundland and Labrador, he argued, had a population that was "growing faster than the jobs [were] growing." To prevent future generations from moving away, Smallwood believed the government had to create thousands of jobs as quickly as possible. Doing this, however, meant taking risks.

"Productive industry – that's our hope. Our only hope," he wrote.

"But Newfoundland is not the first part of Canada that springs into the mind of a businessman in any part of the world if he decides that he would like to start up somewhere in Canada … So if we are to bring them to Newfoundland, we will be forced to offer them inducements. We will be forced to attract them with special concessions … And we must be prepared to take chances. We must be prepared to gamble."