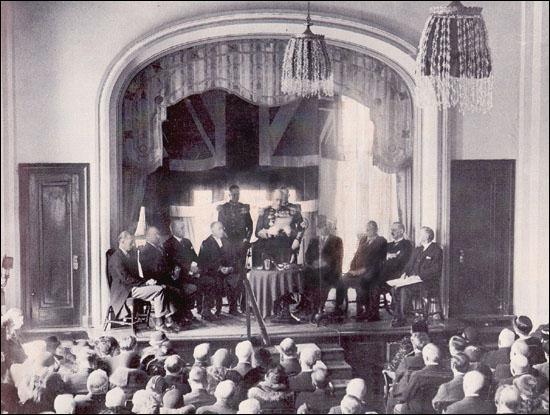

Fishery Modernization During Commission of Government

By the time the Commission of Government was instituted in 1934, technological changes were beginning to present new challenges, as well as opportunities, to the Newfoundland saltfish industry. Members of the Commission government, some merchants, and no doubt a few fishers as well, understood that the saltfish industry no longer provided the appropriate economic returns. A consensus began to form that the future lay in providing a high quality frozen product to the premier east coast American and central Canadian markets. The fresh/frozen fishery became a cure-all that would finally break Newfoundland of its dependence on a supposedly archaic industry whose deleterious influence on the economy and society of the island would be addressed once and for all.

Role of Government

The Amulree Commission had recommended a program of overall modernization (in 1930s terms) for the fisheries, including such things as a system of cooperatives, inspectors based in the two major European markets (Portugal and Italy) and a decreased reliance on credit in the relationship between fisher and merchant. The Commission of Government operated on the principle that its role in the rejuvenation of the fisheries was to encourage cooperative associations on the one hand, and to cultivate private fisheries firms, especially those who might embrace the fresh/frozen industry, on the other. In some senses this was contrary to the initial stated goals of the Commission with regard to the fisheries, namely the encouragement of cooperative arrangements and the awarding of ownership to the labourers. Always within the limiting context of a deep global depression, the Commission worked at enhancing the capacity of the fishing industry. It saw the saltfish economy as backward, needing to be upgraded and professionalized. The Commission encouraged educational programs and fisheries research, and instituted a shipbuilding program. But despite a philosophy which centered on helping create a climate for increased productivity, recurring economic crises and poor fisheries returns during the Depression years continually thwarted the best intentions of the Commissioner of Natural Resources and his fisheries officials.

The Salt Fishery: The Beginning of the End

Despite the Commission’s stated commitment to re-shaping and modernizing the fishing economy, the old salt fishery proved to be resilient. The reality was that thousands of fishers in hundreds of communities around the Newfoundland and Labrador coast operated in a micro-economy which had deep roots and stubborn social and mercantile attachments. The majority of fish merchants in Newfoundland, themselves suffering from adverse currency movements and Depression-induced marketing challenges, were loathe to make wholesale changes to their business system just because a group of unelected administrators in St John’s were asking them to.

There were other factors, external to Newfoundland, which undermined the saltfish trade in the long term. Fish merchants conducted their business in devalued British pounds, and sold fish in southern European, Caribbean, and Brazilian markets for currencies of unstable value. In a world more and more dominated by the economy of the United States, merchants increasingly found that they had to purchase supplies for the fish trade in more valuable American dollars. Though individual fisher families were able to subsist in the outports as producers of low-quality salted and dried fish, the looming currency problem and associated capital flow imbalances of the fish trade could not last indefinitely. The international bond markets would not permit it.

The Bank Fishery

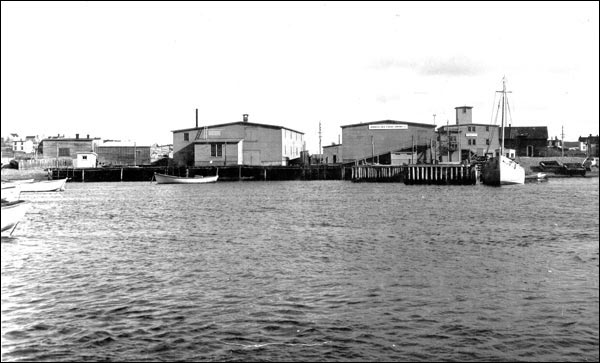

The Newfoundland bank fishery required modernization by the 1930s. The bank fishery was structured around sailing schooners with fishing crews that spent extended periods on the offshore banks. These schooners returned periodically to their home ports with a wet-salted product that was then processed on shore through washing and air drying, similar to the inshore, small-boat product. The deep waters of the banks were well suited to the ships required by the fresh/frozen industry that the Commission was advocating: large factory freezer vessels. These vessels would bring their fresh product, in bulk, to onshore processing centres for final "assembly" into an exportable frozen product.

Several firms, most notably John Penny and Sons, made the transition from old-fashioned schooner-based banker firms to modern fresh/frozen processors. Banker firms, mostly located on the south coast, slowly made the transition to become trawler-based suppliers to frozen fish plants, though the process was prolonged and lasted into the 1950s. Banker operators no longer replaced schooners and related, archaic gear, preferring instead to avail themselves of loan programs and thus invest in upgraded vessels and modern gear. Similarly, the Labrador "floater" fishery, a long distance version of the old inshore saltfish trade, ceased to become a feasible exercise by the middle years of the 1950s, and passed into history.

Panacea: A Fresh/Frozen Fishery Sector for Newfoundland

The Commission of Government felt that the Newfoundland saltfish industry was archaic. Lord Amulree had argued for a more technologically advanced fishery, and this meant moving away from the saltfish industry and exploring other forms of preserving and transporting the cod harvest. The Commission optimistically embraced fresh/frozen production as the cornerstone of future fisheries development, but for various reasons, some of them related to its newness as a technology, the fresh/frozen approach did not really advance during the 1930s. Only a small number of particularly entrepreneurial merchants explored the considerable technical requirements of a frozen fish industry. Meanwhile, advancements in refrigeration technology were being pursued abroad, especially in America. Most notably, in the late 1930s, Clarence Birdseye perfected the process of quick-freezing fish fillets, and frozen food was catching on in American and central Canadian households. This coincided with the increasing use in restaurants and households of “iceboxes” and early refrigerators. All signs seemed to point in the direction of frozen product as being the future for Newfoundland’s fisheries.

By the beginning of World War II, frozen fish emerged as the principal strategy for fisheries modernization under the Commission of Government. The overall program for modernization of the fisheries, however, was proceeding very slowly. Historian Miriam Wright, among others, has pointed out that the saltfish industry was organized socially, around families, whereas the frozen fish industry required industrial organization. Thus there were large social costs surrounding any large-scale modernization of the Newfoundland fishery economy. In 1941, P.D.H. Dunn, the forward-thinking Commissioner of Natural Resources of the day, recognized the importance of the growing frozen fish consumption sector and began to develop a plan to develop a frozen fish industry. Although this effort, like others, was slow to take root in the minds of Newfoundland bureaucrats and merchants, Dunn’s report was important in that it clearly identified American and central Canadian consumer markets as vital to the overall program of modernizing the fisheries through a frozen fish strategy.

In the early years of the war, the new Newfoundland Cold Storage Development Committee was successful in initiating exports of frozen product. This coincided with the wartime employment boom which diverted surplus labour away from the “employer of last resort,” the fisheries, and thus kept production under control. As well, a large number of young men entered the services and went off to the war; this also kept catches down and fish prices firm.

In 1944, yet another important report was produced by Stewart Bates for the federal Department of Fisheries. Bates was a Nova Scotian who was familiar with the problems facing the Atlantic fisheries. Bates disagreed with the majority of Maritimers, and Newfoundlanders, who believed that weak market conditions were the principal problem facing their fisheries. He concluded that poor quality and high export costs were principally to blame. In his 1944 report, he specifically recommended that for Newfoundland, the future lay in marketing frozen fish to the principal markets of the eastern United States and central Canada. The Commission government backed up its philosophical and administrative support of the fresh/frozen fish sector with low-interest loans. The business community was in general supportive of the new industrial thrust, though there were some fears, such as the concern that the “industrial” nature of the frozen fish sector, with fish plants and processing centres, would lead to unionization and thus upward pressure on wages. During the late 1940s, the firms which had embraced the new industry made slow and steady gains in penetrating new markets and refining their production and distribution practices. This laid the ground for a climate of cooperation between government and private enterprise which, while counter to some of the collectivist and cooperative designs of the Commission, lasted for many decades.

Status of the Fishery after World War II

Soon after World War II ended, the Commission’s plan for revitalizing the fisheries was released to the world. It included at its core, the reorganization of the fishery into a tightly regulated industry hinging on 12 to 15 fisheries centres where raw materials would be processed into frozen, smoked, salted, or canned fish. These processing centres would be, in effect, independent fisheries companies, run by private enterprise but regulated by the government. Importantly, the Commission also appreciated the importance of making the fishers shareholders in the industry. The British government was skeptical, however, about the Commission’s ambitious plan. London questioned the considerable reliance upon private firms in the plan, and preferred that the Newfoundland government act in more of an oversight, rather than a regulatory, role. Then, the fisheries plan somehow got pushed aside as other events conspired to grab the attention of policy-makers and elected officials.

The global economy was left traumatized by the cataclysm of World War II and economic power structures were shifting. Worried about a post-war collapse in fish prices, the Commission allowed a group of private firms, organized as the Newfoundland Associated Fish Exporters Limited (NAFEL), the sole right to export fish from Newfoundland in 1947. As a private marketing organization, NAFEL had no mandate to develop markets and relied on voluntary standards for quality of fish products among its members. Without the power to establish standardized production, NAFEL could do little to foster improvements in the fishing industry.

Constitutional issues overshadowed fisheries reform. Newfoundlanders and Labradorians began finally to consider their future after more than ten years of Commission government. The Commission’s ambitious plan was thus lost in the rhetoric surrounding the build-up to the referenda of 1948 and the questions surrounding Newfoundland’s future. The choices were as exciting as they were diverse: continued Commission government, independent statehood, overtures to the United States, or provincial status within the Dominion of Canada. Newfoundlanders and Labradorians chose Canada by a narrow margin. NAFEL continued as a federal agency with exclusive marketing rights for provincial salt fish until 1959 when Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada in 1949. However, the agency continued to have little authority or power to improve the saltfish industry.

Assessment

During the Commission government era of the 1930s and 40s, two related processes worked to complicate the Newfoundland fishing economy. A saltfishery that had persisted for 300 years ran up against the realities of an increasingly integrated global economy and the dangerous vagaries of global currency markets. The situation facing the Commission government was a stark one: an industry that was the primary employer of the majority of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians was in the process of collapsing.

The solution presented by the Commission government, a technologically modernized industrial fishery, complementing other land-based resource industries such as forestries, and capped by a new form of industrial organization centred on professionally managed co-operatives, was ambitious and promising. Its enactment, however, was delayed by World War II when Newfoundland’s strategic position in the Atlantic rendered it an important ally. Economic good times, unfolding under the clouds of global war, forced fisheries reform onto the back burner. When the war ended, other important questions occupied Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, and the fisheries question was still far from answered.