New Findings on Cabot

In 2007, Evan Jones published an article in Historical Research about the extraordinary claims that historian Alwyn Ruddock made about John Cabot. Ruddock had been working on a book which she said would revolutionize Cabot scholarship, but she died before anything was published and left strict orders for her research to be destroyed. All that remained was a brief chapter outline. The document did not identify any of Ruddock's sources, but it did contain a number of clues that Jones, a discovery historian, knew to be invaluable. He hoped that by publishing an article on Ruddock, he could enlist the help of other scholars in investigating her claims.

His hopes were well founded. In 2009, Jones and an international team of researchers established the Cabot Project to untangle the mysteries that Ruddock left behind. They have made significant progress, not only in verifying some of Ruddock's claims, but also in uncovering entirely new information on Cabot and the Bristol discovery voyages of the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

Why So Much Uncertainty?

Despite his present-day fame, the 15th-century Venetian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Caboto) remains shrouded in mystery. We know that he arrived at England sometime between 1493 and 1495, obtained a commission from Henry VII to explore unknown lands, and then led an expedition in 1496 that ended in failure. He set out again in 1497 and reached the New World, which he falsely believed to be Asia. He explored the coast for a month, returned to England, and was rewarded with a pension from the king. Cabot made a third attempt in May 1498, this time with a fleet of five ships.

We do not know what he did immediately after arriving in England or how he persuaded Henry VII to support his voyages. The location of his 1497 landfall remains uncertain, and almost nothing is known about the 1498 voyage; it has long been assumed that Cabot and most of his fleet were lost at sea.

Our knowledge has been limited by a lack of documentation. Moreover, the English did not immediately view Cabot's voyages as truly important. He was searching for a trade route to Asia and its valuable spices, silks, and precious stones. There was no comparable commercial value in what seemed to be a New World. Codfish was plentiful, but Britain's domestic and Icelandic fisheries satisfied most of its demand for cod at that time. It was not until England became interested in colonization in the late 1500s that its government saw that Cabot's voyages could bolster an English claim to the region.

Cabot's son Sebastian had further obscured the historical record by claiming many of his father's accomplishments as his own. Scholars recovered more documents concerning Cabot during the 19th and 20th centuries, but there were still many important questions that remained unanswered.

Ruddock's Claims

When Evan Jones published his article in 2007, only 25 records were known to scholars. Ruddock, though, said that she had discovered an additional 21, which would turn “the Bristol/Cabot story upside down” (Jones "The Quinn Papers", 13). She made the following claims:

- Italian investors helped pay for Cabot's voyages.

- An influential Italian cleric named Fra Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis helped put Cabot in touch with Henry VII.

- Cabot arrived at North America in 1498 with Carbonariis and a group of Italian friars.

- Carbonariis and the friars established a religious community at Newfoundland, probably at Carbonear.

- Cabot spent two years exploring North America's east coast. He sailed as far south as Venezuela, turning back when he encountered Spanish explorers.

- He returned to England in the spring of 1500 and died four months later.

- In 1499, a previously unknown English explorer named William Weston led an expedition to the New World. He sailed north of Newfoundland, along the Labrador coast to the Hudson Strait.

Since 2007, Jones and a team of researchers have been trying to verify Ruddock's claims and locate her sources. They have had considerable success.

New Evidence: The Condon Documents

One of the first people to join the search was Jeff Reed, a retired American researcher who had known one of Ruddock's closest colleagues, the discovery historian David B. Quinn. After Quinn died in 2002, a large number of his letters and papers were deposited at the Library of Congress. Reed volunteered to go through them. He found many that bore on Ruddock's work, as well as a number involving the archivist Margaret Condon.

Condon's research interest was Henry VII, and in the late-1970s, she had uncovered two documents at the British Public Record Office (now The National Archives) that related to the Bristol discovery voyages. One was a letter from Henry VII suspending legal proceedings against the Bristol merchant William Weston, so that he could lead an expedition to the “new founde land”. It was probably written in 1499. The other document recorded a £100 payment made by the king in 1502 to “Hugh Elliot of Bristol and his associates”, partial compensation for the costs incurred in a voyage to the “new found isle”.

Condon told Quinn about her findings, but he advised against publication until Ruddock released her book. In 2010, Condon and Jones published both documents alongside their analysis, in the journal Historical Research. In so doing, they shed important new light on Bristol's discovery voyages and substantiated one of Ruddock's claims – that William Weston had led an expedition to the New World in 1499. She was not making things up, and her other claims therefore warranted further investigation.

A Second Claim Verified

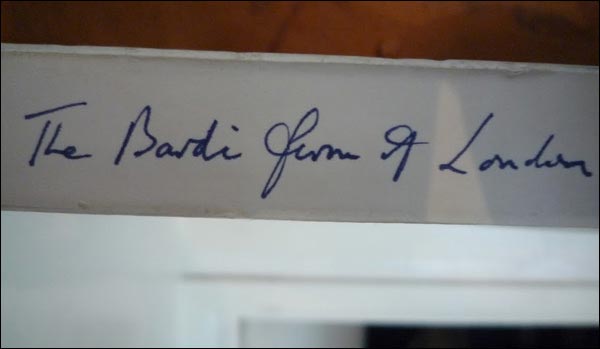

Another advance came in 2010, when the current owner of Ruddock's house invited Jones and Condon to visit. Ruddock's study was largely untouched, although all of her documents had been destroyed, in accordance with her will. Attached to one of the cubbyholes where Ruddock filed her documents was a sticky label that read “The Bardi firm of London”. It was an important clue. One of Ruddock's most original claims was that Cabot had Italian investors – his voyage was not exclusively backed by English money as previously believed. The Bardi was a Florentine banking house with a branch in London.

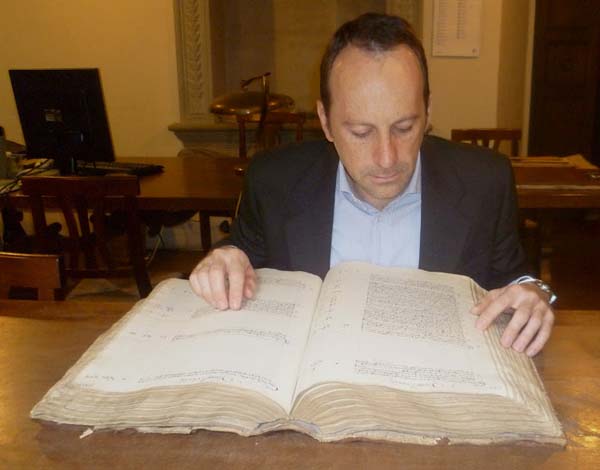

Jones and Condon contacted Francesco Guidi-Bruscoli, an economic historian specializing in late-medieval Italian merchant bankers. He was aware of Ruddock's claims and had already tried to locate some of her sources in Florentine family archives, but without any success. Now he had a concrete lead. Guidi-Bruscoli traced the Bardi records to the archives of the Guicciardini, an old and prominent Florentine family. He found a ledger that contained the following entry: “John Cabot, of Venice, on 27 April [1496], is debited for £10 sterling, paid in cash to Lorenzo Morandi towards the 50 nobles sterling [£16 13s 4d] our Aldobrandino Tanagli ordered us to pay him so that he could go and find the new land” (Translated, Guidi-Bruscoli 2012).

The entry proved that Cabot, like Columbus and other explorers of the time, had benefitted from Italian money. “Despite the brevity of the entry, it opens a whole new chapter in Cabot scholarship, introducing an unexpected European dimension and posing new questions for the field,“ Guidi-Bruscoli wrote in Historical Research in 2012. "Why, for instance, might an Italian bank have chosen to fund the expedition? And what did it, or could it, have hoped to get in return?" The possibility also exists that other Italian firms backed Cabot as well, but so far there is only proof for the Bardi. By finding the ledger, Guidi-Bruscoli deepened our knowledge of the Cabot voyages, provided future research for scholars, and authenticated a second of Ruddock's claims.

Other Areas of Research

The Cabot Project continues to investigate the Bristol voyages and Ruddock's assertions. Jones and Condon are working in various English archives to uncover more documents. According to the project's website, they have located additional records of William Weston's 1499 voyage and found “information that supports Dr. Ruddock's claim that Cabot returned to England in the Spring of 1500.” An article is forthcoming.

Ruddock's other claims have not yet been substantiated. Among the most extraordinary are her assertions concerning the 1498 voyage. If she was correct, then Carbonear would be North America's oldest European Christian community. Peter Pope, an archaeologist at Memorial University, has been surveying the Carbonear area for the remains of European settlement but has not uncovered any evidence of colonization before the 17th century.