The English Fishery and Trade in the 18th Century

The British migratory fishery at Newfoundland reached its height in the 18th century in terms of production, employment, and revenue. It overtook the French fishery, which had been the larger of the two during the 17th century, in part because the French were forced off most of the island of Newfoundland after 1713 and in part because the English fishery had expanded beyond the old limits. In addition, secondary activities such as the salmon, and later the seal fisheries became significant.

This expansion, both in geography and in economic activities, made permanent settlement in Newfoundland possible for the first time. The number of permanent residents was small, but significant. This development alarmed those who still favoured a purely migratory ship fishery, but to the West Country merchants who controlled the fishery and trade, the growth of a resident population was an advantage. Expansion of the fishery and settlement generated great prosperity, and a few merchants became tremendously wealthy and powerful, owning fleets of ships, employing thousands of fishermen, and dominating the lives of Newfoundland settlers.

West Country merchants became wealthy enough to diversify their activities so that, when next the migratory fishery found itself in difficulty, they had alternative sources of income. At the same time, the encouragement given to settlement, expansion and diversification in Newfoundland eventually allowed the residents to dominate the fishery.

This meant, paradoxically, that the success of the British migratory fishery at Newfoundland in the 18th century set the stage for its own extinction. However, this success was preceded by a quarter century of great difficulty.

A Disastrous Quarter Century

Ship and Boat Fisheries - a Symbiosis

When the 18th century opened, England was at peace after a decade of war which had severely damaged the fishery. The demands of the navy for seamen, the interruption of the trade, the devastation caused by the French in Newfoundland, had all burdened a fishery already weakened by a pre-war trade depression. The traditional ship fishery was in decline, and the boat fisheries (both planter and bye-boat) were expanding.

Thus there were significant changes occuring in the fishery when peace was restored. This made it hard for West Country fishing interests to respond effectively to the great increase in competition that now developed. Many towns with little or no experience in the Newfoundland trade, such as Cork, Liverpool, Chester, and Hull, took advantage of the post-war release of credit and labour to become involved in a variety of maritime trades, including that with Newfoundland. London, which had four vessels at Newfoundland in 1684, had 73 in 1698. The West Country hold on the Newfoundland trade seemed threatened.

Some towns responded by trying to revitalize the traditional ship fishery. Dartmouth merchants, for instance, returned to the old ways and so did the North Devon towns of Barnstaple and Bideford. But conditions did not favour the ship fishery for two major reasons. First, it had always been important to gain first access to the best fishing rooms by arriving early in the spring. This was increasingly difficult because many fishing rooms were now occupied all year, not only by planters but also by merchants who were shifting more of their operation into trade and into the boat fisheries.

Second, the ship fishery had always needed large numbers of men - it was normal to hire six men for each of the ship's fishing boats, together with a large shore crew. Merchants now found that enough labour was not always available. During the war, men were pressed into the navy or chose to remain in Newfoundland, working in the boat fisheries - and the boat fisheries had advantages. One was that the fishermen were paid in wages, not in shares. Given that outcome of a fishing voyage could be very uncertain, wages were more secure. The boat fishery continued to grow even after peace was restored and some ports experienced real hardship as a result.

Some West Country ports abandoned the old methods and adopted a cross between boat and ship fishery. Ships still went out each spring, but with smaller crews using smaller boats. Such a reduced operation could not collect a full cargo by the end of the season, nor was it intended to. Instead, the balance of the cargo was acquired from the boat fishermen. In addition, a substantial proportion of the voyage's revenue came from transporting passengers and freight for the boat fishery.

This kind of operation shows that many West Country merchants not only accepted the presence of a permanent population in Newfoundland, but had learned to adapt to, and prosper from it. Migratory and resident fisheries were becoming integrated, and over the century West Country merchants reduced their direct involvement in the fishery in favour of an increased commitment to the supply trade.

War

The War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1702, lasted until 1713, and brought the British fishery at Newfoundland to its lowest point ever. There was a vicious land war in which the French attacked and destroyed English Shore settlements. St. John's was captured twice. Trans-Atlantic commerce was interrupted by enemy privateers, by impressment, and by government embargoes on trade. Spain was an enemy, so the fishery's largest market was closed for a decade. Many Italian market ports were also closed because they were under the control or influence of the Spanish crown. Only Portugal continued to purchase English salt cod.

Ironically, there were record catches at Newfoundland, with some boats taking over 400 quintals in a single season. But without uninterrupted trade across the Atlantic and free access to markets, the fishery could not prosper. Both the migratory and sedentary fisheries contracted. The number of fishing ships (including the new hybrid kind) dropped from 171 in 1700 to 20 or 30 on average during the war years. In 1708 only seven sack ships were recorded at Newfoundland, compared with nearly 50 in 1700. The total catch by migrant and resident fishermen between 1702 and 1709 averaged under 100,000 quintals per year, compared with 300,000 quintals per year before the war.

Fishery Failures

Conditions did not improve after the war. Markets and trade opportunities revived, but the fishery itself began to fail. For the next ten years both French and English fishermen at Newfoundland experienced disastrously poor catches. For many merchants as well as planters, this situation was the final straw. A number were forced into bankruptcy. The population of Newfoundland shrank as residents returned to England or emigrated to America. The number of West Country ports active in the Newfoundland trade was further reduced.

At the same time, the failure of the fishery after 1715 played a significant role in consolidating West Country control over the Newfoundland fishery and trade. Those who could do so moved into other commercial activities. The London ship owners, for instance, who had greatly increased their involvement in the sack ship business by the end of the 1600s, now withdrew from the trade completely. The competition which had seemed to threaten West Country dominance in the fishery in 1700 disappeared.

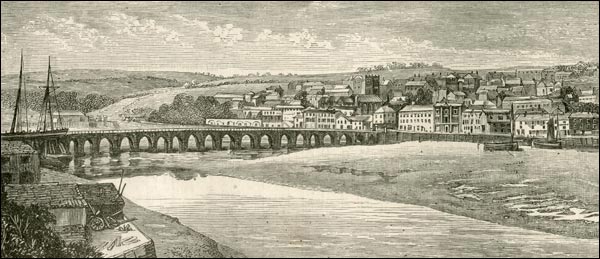

For the fishing merchants and planters who had no alternative, it became a matter of either sticking with the Newfoundland fishery or being defeated by it. And many were defeated. But when the fishery recovered late in the 1720s, those who survived had improved their position, both relatively and absolutely. For the next 60 years, the Newfoundland fishery would be dominated by the merchants of just a few towns: Dartmouth, Poole, Exeter (through its outports of Topsham and Teignmouth), and to a lesser extent Bristol and Jersey.

The Rise of the English Bank Fishery

The disastrous years from 1702 to the mid-1720s caused other significant changes in the fishery. One of these was the birth of the English bank fishery. The English had always preferred the inshore dry fishery, leaving the banks to others, notably the French who were skilled at the wet cure required on the banks and who had a strong domestic market for green cod. But some fishing merchants took a second look at the bank fishery as the ship fishery faded and inshore fishing yields began to plummet. Bankers were far more productive per man, they required smaller crews, and were relatively cheap to build. Such cost advantages more than compensated for the lower price which the banker's catch commanded.

The lower price was a result of the cure. The English were not able to copy the French green cure. Instead, the English bank fishermen salted the fish heavily in the hold and brought the catch to shore, where it was dried. The quality of the fish was not as high as that produced by inshore fishermen, but large numbers continued to exploit the banks.

It is difficult accurately to estimate the size of the bank fishery in this period. Before 1769 the official records did not distinguish between bankers and inshore fishing ships; all were listed under the collective term "British fishing ship." Though the most impressive growth in the bank fishery occurred after 1763, it was very significant earlier in the century.

Generally it was Devonshire fishermen who favoured the new bank fishery. They had long dominated the "Southern Shore" from St. John's to Trepassey, a stretch of the coast which had a clear locational advantage for exploiting the banks. Fishermen north of St. John's continued to concentrate on the inshore fishery.

The bank fishermen also made money by carrying passengers back and forth to Newfoundland. Since they did not have large crews, the bankers had plenty of room for passengers. At a fee of £3 per passenger, one way, and 20 shillings per ton for supplies and provisions, a banker could defray much of its operating costs from passage-money alone. In a bad year, the passage-money earned by transporting 60 or 70 fishermen and their supplies across the ocean and back could spell the difference between a disastrous and a profitable voyage. It is not surprising that a close relationship developed between the bank fishery, which welcomed passengers, and the migratory bye-boat fishery, whose fishermen needed transportation.

The Bye-Boat Fishery

As an inshore activity, the bye-boat fishery was affected by the poor fishing after 1715, but not as badly as the resident fishery. With no permanent facilities to maintain, the bye-boat men had lower overhead costs. They often rented fishing rooms from planters, and produced more fish using fewer men. Not surprisingly the importance of the bye-boat fishery increased during this period.

Like the bank fishery, the bye-boat fishery was most popular among the men of South Devon. And in Newfoundland, the bye-boat fishery was most prominent on the "Southern Shore," where the bank fishermen were based while in Newfoundland. The bank and bye-boat fisheries were linked and inter-dependent. The growth and expansion of one contributed to the growth and expansion of the other.

The Resident Fishery

In contrast, the resident fishery suffered greatly during the early part of the century. The war bankrupted many planters, and the depression which followed caused further hardship. As earnings fell, planters were forced to buy wintering supplies on credit from English and American traders. They then had to turn over the next season's catch to their creditors at a price determined by the traders. Thus many planters found themselves in a vicious debt cycle from which there seemed no escape, except emigration to America.

Because this was illegal, it is difficult to estimate accurately how many left Newfoundland in this way. One naval officer claimed that as many as 1,500 fishermen went to America in a particularly hard year. While many of these would have been seasonally-employed servants, not planters, we do know that the resident population showed little growth during this period; it may even have declined.

This may explain why the resident fishery did not take greater advantage of new opportunities for expansion that existed after the war ended in 1713. The Treaty of Utrecht, which brought the War of the Spanish Succession to an end, recognized British sovereignty over the entire island of Newfoundland. France retained important fishing rights on the coast between Cape Bonavista and Pointe Riche (the so-called "French Shore"), but shifted the centre of its fishery to Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island and abandoned Plaisance.

The English were slow to move into the areas formerly used by the French. The main reason for this was the failure of the fishery, which affected the new regions as much as the old. Residents and others would have been too preoccupied with surviving where they were, without adding the risk of venturing into unknown territory.

Labour Problems: The Irish Connection

The Newfoundland fishery was so uncertain in the years after 1715 that West Countrymen became unwilling to participate. They could not be certain that they would earn enough to pay for their return passage. As a result, and for the first time on a significant scale, the West Country fishing fleets began to pick up workers in Ireland. The fleets had long been accustomed to stop at Cork and Waterford for provisions while en route to Newfoundland. Now they began to collect men as well. Most Irish recruits, like those from the West Country, were landsmen from the rural hinterland, attracted by the possibility of work in Newfoundland. Their lack of skills was no more an obstacle than it was for West Country landsmen. Besides, the new bank fishery demanded fewer skills than the inshore fishery. By the 1720s practically all the West Country fishing towns were recruiting Irish workers for Newfoundland.

The recovery of the fishery at the end of the 1720s did not end this practice. A series of famines struck Ireland at that time which maintained, even increased, the flow of Irish workers to Newfoundland.

Recovery: The English Fishery After 1725

Fishing and Trading

The years between 1702 and 1725 had demonstrated just how risky the fishing industry could be. Consequently, as more and more residents bought supplies from them on credit, the merchants began to concentrate their efforts in the supply trade.

Whether they carried men from Ireland or general cargoes from England, it is obvious from the volume of cargoes carried by "fishing ships" that more people were being supplied than the merchants' own fishing crews. Those West Country ports which remained most active in the sedentary fishery were, predictably, most heavily concerned with the supply trade.

Poole, with substantial interests in Trinity and Bonavista bays, took the lead in this trend. Others soon followed. Exeter, which freighted mostly salt in 1720, regularly freighted provisions and manufactured goods ten years later. Dartmouth, which freighted almost nothing in 1720, became heavily involved in the supply trade before the end of the decade. The fishing ships had become traders as well, and their backers were increasingly tolerant of permanent settlement.

Yankee Competition

American trading vessels appeared at Newfoundland as early as the 1640s, and were regular visitors to the fishery by the 1670s. But throughout the 17th century the Americans had traded on a speculative basis. In the 18th century, the Americans became much more organized, with factors residing year-round, in charge of permanent warehouses. This enabled them to sell goods all year round, wholesale and retail. They received in exchange cash - though this was extremely rare - or bills of exchange. If bills were not available, the factor might accept refuse cod for sale in the West Indies. The fish could be exchanged there for bills of exchange, a return cargo, or a combination of both. This kind of trade was extremely important for the Americans, and their trade with Newfoundland grew steadily. Twenty American vessels were counted in 1721; in 1748 the number was 95.

While some West Country merchants complained about unfair competition, most had no objection to American traders. Yankees supplied the fishery with cereal products, livestock, molasses, and especially rum. These goods did not compete with those imported from England and Ireland. If anything, the Yankee trade was complementary to that of the English merchants.

Objections to the Americans came from two sources and were related to a common problem. Merchants who dominated a particular bay or district felt threatened by emigration to America, because too many people escaped their debts and obligations in this way. The British government was also concerned, because emigration threatened the fishery's role as a nursery for seamen. But so long as most residents and merchants tolerated, even welcomed the American traders, nothing was done to restrict their presence in Newfoundland.

West Country Traders

By the 1720s the West Country merchants were following the example of the American traders. They now had extensive and permanent properties in Newfoundland to support their fishing operations. The fishing rooms of the 17th century, available on a first-come, first-served basis, had almost disappeared. Most of them had been quietly (and illegally) occupied on a permanent basis by the crews and servants of West Country fishing merchants, and ownership was no longer disputed. The rooms were treated as private property, and when a merchant died, his rooms passed to his heirs.

The old distinction between "Western Adventurers" and "planters" was becoming blurred and irrelevant. The West Country fishing merchants had "planted" their businesses in Newfoundland, if not themselves and their families, and their growing involvement in the supply trade reinforced this trend. To ensure proper management of their operations, merchants often sent junior members of their families to live in Newfoundland. Many remained on the island for considerable periods of time. The West Country merchants were diversifying their activities, and were no longer exclusively fishing merchants. They were also suppliers, shippers, wholesalers, and retailers. This gave the larger merchants enormous resiliency during the periodic outbreaks of war. A merchant's overall level of business would not suffer nearly as much as it did in the 17th century, when almost all of his business would have been concentrated in the ship fishery. War still caused the migratory fishery to contract, but the merchant could still do business with planters and boatmen.

The Winners

Diversification and resiliency permitted the accumulation of considerable wealth and influence both in England and in Newfoundland. Joseph White, head of a prominent Poole fishing merchant family, died in 1772; his estate was worth £130,000. Such wealth gave a merchant family much greater economic control than had been customary in the previous century.

More and more, merchants owned their ships outright. Share ownership still persisted, but it no longer involved several principal shareholders. Instead, there was usually a single shareholder with the controlling interest, and a host of smaller investors, often sources of quick cash. A few merchants even owned fleets of shipping. The Dartmouth firm of Newman and Holdsworth owned ten ships and vessels at one point, and Joseph White owned 14 in 1750. Other merchants also owned warehouses, vineyards, "wine houses," "fish houses," and other commercial property in market countries like Spain and Portugal.

Markets

If diversification was an important factor in the survival of many West Country fishing merchants, the fish trade still remained their most important activity, and Spain and Portugal were still their most important markets. Commercial treaties with both countries, together with the continued decline of the Spanish economy (which made that country increasingly dependent upon foreign suppliers), reinforced the trading patterns which had been established during the previous centuries.

The successful outcome of a voyage nevertheless continued to depend on luck, a knowledgeable sailing master, and reliable contacts in key market ports. Competition in the lucrative Iberian market was considerable. Spain consumed around 400,000 quintals of saltfish annually, and Portugal took another 150,000 or more. The British fishery supplied an important proportion of that total. In 1770 over 600,000 quintals were exported from Newfoundland to "foreign markets", a term which included the Italian and West Indian markets, as well as Spain and Portugal.

The French fishery produced another 350,000 quintals at mid-century, although much of this - perhaps 250,000 - was intended for the domestic market. The American (New England) cod fishery produced around 250,000 quintals annually. Most of this went to the West Indies as "refuse" fish, but an increasing amount was sent to southern Europe. By the 1760s Yankee traders were selling 60,000 quintals of saltfish annually at Bilbao alone. Such competition to the British fish trade may well have contributed to the animosity felt by some of the West Country merchants towards the Americans.

Still, the lion's share of the market belonged to the West Country merchants. Despite an unsteady start at the beginning of the century, the British dominated the North Atlantic fish trade once the fishery began to recover late in the 1720s. All branches of the fishery prospered, especially the bye-boat fishery. By 1735 the British cod trade was supplying 400,000 quintals to foreign markets, a figure which exceeded the total catch of the French fishery.

Even wars did not seriously damage the English trade. There were some difficulties during the War of the Austrian Succession (1739-1748), but thereafter the British fishery prospered more than ever before. Exports to foreign markets exceeded 500,000 quintals in 1752. Unprecedented levels were also reached in the number of bye-boats (581 in 1748), inhabitants' boats (944 in 1752), passengers (over 5,900 in 1752), bye-boat men (nearly 5,900 in 1750), and planters (over 10,000 planters and servants in 1754; about two-thirds seasonally employed).

Between 1755 and 1763 the Seven Years' War caused the fishery and production to contract. But from 1763 to 1775 the British fishery again expanded to new heights of prosperity and productivity. Not once in the decade after 1763 did the volume of fish caught by British fishermen at Newfoundland fall below 500,000 quintals; twice it exceeded 700,000 quintals.

Meanwhile, France had lost all its North American possessions apart from the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, ceded as a seasonal base and shelter, hardly an adequate substitute for what had been lost. French fishermen could also use the French or Treaty Shore. The French remained important at Newfoundland, but the British had clearly become supreme in the fish trade to Europe. The French were no longer serious competitors.

One reason for this success was the nature of the supply trade which supported the British fishery at Newfoundland. As we saw, Ireland and especially North America had become the fishery's most important sources of provisions. Most supplies used by the French fishery came from Europe, and were much more expensive. Consequently the French fishery was not as competitive, and began to lose ground in southern European markets.

A second important factor in explaining the remarkable rise of the British fish trade was the presence of the sedentary fishery. Whenever war caused the migratory fishery to contract, the sedentary fishery would expand to take up much of the slack. This meant that the British fishery never stopped producing. In contrast, the French resident fishery was in steady retreat throughout the 18th century, and the French fishery remained primarily migratory. This meant that in time of war most of its fishery was suspended. Markets were lost, and proved difficult to recover. After 1763, the French fishery was exclusively migratory, subject to complete interruption with every war. This fact alone gave the British an incomparable advantage in the North Atlantic fish trade.

The End of Monopoly : the Later 18th Century

The British conquest of Canada during the Seven Years War had serious implications for the Newfoundland trade. Before 1763 it had been extremely difficult for newcomers to break into the fishery and trade at Newfoundland. The West Country had established a virtual monopoly, and controlled the planter fishery. Speculative trading voyages were therefore unlikely to be profitable. The conquest of Canada helped to change this situation.

As a regular trade developed between Britain and Quebec, traders would stop at Newfoundland to see if a cargo could be arranged. Many of these were Scots, eager to develop new markets for their rapidly industrializing economy. Interest in Newfoundland was concentrated in the port of Greenock, which had sent ships to the fishery as early as 1725, the object being to smuggle European products such as lace, silks, to British American colonies. Both Scottish and Irish shipping increased. As these newcomers began to make regular visits they established permanent warehouses on the island. Though the level of their activity did not rival that of the West Country merchants, they had cracked the monopoly.

Few of the West Country merchants were disturbed. None of them had abandoned the fishery altogether, and in the fishery their dominance was secure. The 1760s and early 1770s were the best years ever for the fishery. Exports increased, yet prices remained steady. Employment soared, with perhaps 20,000-30,000 men working in the fishery. The migratory fishery prospered the most, especially the bank fishery, and overshadowed the sedentary fishery, which itself had grown significantly. That British administrators still believed that the resident fishery was undesirable and ought to be discouraged shows how little they understood the situation. The migratory fisheries were, in fact, dependent on the resident fishery; and the resident fishery was creating a genuine Newfoundland society.