Tourism after Confederation

Newfoundland and Labrador's tourism industry continued to grow after Confederation, but at a slow pace. Joseph Smallwood, premier from 1949-1971, embraced the industry as a way to diversify the economy, create jobs in outport communities, and introduce the province to potential investors. But he also recognized that extensive improvements were first needed in transportation and accommodations. Thus, the province embarked on a program of modernization before promoting itself to tourists.

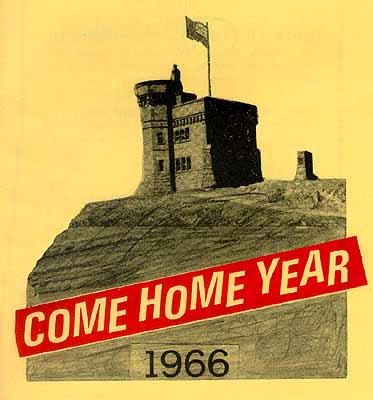

As in previous decades, the province's underdevelopment also served as its main selling point. Rural landscapes and outport culture were central to advertising campaigns directed at middle-class families disenchanted with city life. Expatriate Newfoundlanders and Labradorians were also targeted by promotional strategies similar to those used in the first half of the 20th century. Cultural tourism grew in popularity and state-funded festivals like Come Home Year in 1966 and Cabot 500 in 1997 drew tens of thousands of visitors. Although small by international standards, the industry became an important source of revenue and employment by the end of the century, particularly in outport communities.

Strategy of Modernization

Newfoundland's economy was fragile at the time of Confederation. The centuries old saltfishery remained the province's largest employer, but struggled to compete in a modern industrialized world. Unemployment was high and per capita incomes about half the Canadian average. At the same time, a brief period of prosperity during the Second World War had boosted standards of living beyond what the post-war economy could maintain. Many people moved to other provinces in search of better employment and other opportunities.

Smallwood's Liberal government hoped to address these problems by modernizing the economy and diversifying it into new industries. Tourism was believed to have much potential. In 1950, the government asked the Director of the Canadian Government Travel Bureau in Ottawa, Leo Dolan, to review the province's tourism industry and recommend ways to expand it. Dolan reported that Newfoundland could become a "mecca for travellers from all parts of the world" (qtd. in Overton, Making 27) in five to 10 years if it could overcome three main obstacles.

First, there was a pressing need to develop the infrastructure of the tourism industry. Improved road, ferry, and air transport were vital. So were better accommodations, food services, entertainment, parklands, marked historic sites, and other attractions. Second, an effective advertising campaign would have to be developed to entice travellers. Third, local people would have to be taught the economic value of the industry and trained in how to cater to tourists - a "tourist consciousness" would have to be developed.

In the coming years, the government invested heavily in these areas, relying to a considerable extent on federal funds. It appointed a Director of Tourist Development in 1952 and established a Tourist Development Loan Board in 1953. The board helped to pay for new accommodations at Corner Brook, Trinity, and other communities. In 1965, the Holiday Inn chain announced it would open four establishments on the island, at St. John's, Clarenville, Gander and Corner Brook.

Attention was given to developing tourist attractions as well. The government passed the Provincial Parks Act in 1952 and two years later opened the Sir Richard Squires Memorial Park near Deer Lake; others soon followed. The province's first national park, Terra Nova, opened 1957. That same year, the government reopened the Newfoundland Museum (now The Rooms Provincial Museum Division) in downtown St. John's, which the Commission of Government had closed in 1934. Signal Hill was designated the province's first national historic park in 1958, followed by Cape Spear in 1962.

Transportation improved dramatically. By the end of the 1960s, bridges and causeways replaced some of the smaller ferry services, more vessels operated on the Gulf crossing, and there was regular service between Nova Scotia and Port aux Basques. In 1968, a summer ferry service operated between Argentia and Nova Scotia. Air Canada provided national and international services from St. John's, Gander, and Stephenville, with regular flights to Halifax, Sydney, Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton and Vancouver. The locally owned Eastern Provincial Airways (EPA) provided regular passenger service between St. John's, Gander, Deer Lake, the Maritimes, and St. Pierre et Miquelon. An important milestone was the completion of the Trans-Canada Highway in 1965, with its associated roadhouses, picnic sites, and campgrounds. Motorized tourism, already popular elsewhere in North America, was now possible on the island.

Open for Business

The government developed a tourism promotion to coincide with the official opening of the highway in 1966. "Come Home Year" invited expatriate Newfoundlanders and their descendants back to the island to witness the many improvements that had taken place. Approximately 50,000 visitors were expected. The government was key in organizing the event. It chartered an additional ferry for the Nova Scotia to Port aux Basques crossing, and produced an array of promotional materials, from information booklets to a new license plate. Field workers organized community committees to assist in the celebrations, while training was provided to local hospitality workers in how to treat tourists.

The event produced about $45 million in direct revenues. It signaled the start of Newfoundland's new tourist development program, with the government playing a central role. It also laid the groundwork for future advertising campaigns. Newfoundland was a place where travellers could enjoy modern conveniences and still connect with nature, a simpler way of life, and a unique outport culture. "But even with all the changes and progress, our people remain same as always; friendly, hospitable, proud and happy, the traits that have made us so well-known," said one promotion (qtd. in Overton, "Coming Home" 96).

Tourism After Smallwood

The state continued to play a key role in the industry after the Smallwood era. A provincial Department of Tourism was established in 1973, which became the Department of Tourism and Culture in 1993. Cost-sharing agreements between the national and provincial governments did much to develop the industry. Gros Morne National Park was established in 1973, Port au Choix National Historic Park in 1974, and L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Park in 1977. New provincial parks also opened.

In 1979, the Newfoundland government signed a $13.2-million Tourism Agreement with the federal Department of Regional Economic Expansion (DREE). The money helped to restore historic buildings and houses, develop packaged tours for special interest groups, improve food services and accommodations, and pay for marketing campaigns. By the end of the 1980s, Cape Spear's lighthouse had been restored, and a hiking trail, interpretation centre, and picnic area installed. Several Norse dwellings were reconstructed at L'Anse aux Meadows and an interpretation centre opened. Some communities resettled under the Smallwood regime were also repackaged as tourist attractions.

On Labrador's southeast coast, archaeological work was attracting tourists to Red Bay, a fishing village and former site of several sixteenth-century Basque whaling stations. In 1978, Parks Canada's Underwater Archaeology Service began work on excavating the remains of the San Juan, a Basque whaling ship. Red Bay was subsequently designated a National Historic Site, and interpretation centres and other tourism facilities were installed in the coming years.

By 1984, tourism had become the province's third largest employer, after the fishery and the construction industry. It included accommodations and restaurant staff, outfitters, transportation workers, interpreters, tour guides, civil servants, entertainers, craftspeople, and advertising personnel.

Cultural tourism experienced a surge in the 1990s, as the province prepared to celebrate the 500th anniversary of John Cabot's arrival at North America. Government invested heavily in the event, and festivities included plays, concerts, conferences, and a visit from Queen Elizabeth. Its centerpiece was the voyage from Bristol, England, to Bonavista, Newfoundland, by a replica of Cabot's ship, the Matthew. The province estimated that 69,000 visitors injected $51 million into the local economy and the American Automobile Association named Cabot 500 the most important tourist event in North America in 1997. The government supported other large-scale cultural events in the coming years, including the 50th anniversary of Confederation in 1999, the Viking Millennium in 2000, and Cupids 400 in 2010 (celebrating the 400th anniversary of John Guy's arrival at Cuper's Cove in 1610). Labrador tourism received a boost in 2005, when Parks Canada established the Torngat Mountains National Park.

Marketing Outport Culture

Advertising has always been vital to the industry's success. Marketing campaigns became more sophisticated with time, but the message remained largely the same: Newfoundland and Labrador is a place frozen in time where tourists can get away from it all. Much is made of the province's rich heritage, picturesque fishing villages, and majestic scenery. It offers expatriates a chance to reconnect with their childhoods and a happier time. City folk can experience the beauty and solitude of a rural setting, while enjoying a cultural exchange with friendly outport people. In contrast to the kind of mass tourism provided by resorts, theme parks, and cruise ships, the province claims to offer visitors a unique and more authentic experience.

However, one criticism of tourism campaigns is that they romanticize and depoliticize Newfoundland and Labrador society. Despite widespread underdevelopment and unemployment, outport residents are portrayed as happy, generous, proud, and independent. Class conflicts and social inequities are swept aside and replaced by images of a simple folk who are contented with their lot in life.

At the same time, the industry has done much to revitalize rural economies in the wake of the 1992 cod moratorium. By the end of the decade, tourism had replaced the fishery as the economic base in some rural communities. In 2009, the government identified tourism as one of the province's "greatest economic drivers" (Uncommon Potential, page 6). It estimated the industry accounted for 12,730 jobs and contributed $790 million to the provincial economy annually.

Despite significant growth and government investment, the industry faces several challenges. Tourism is intensely competitive and Newfoundland and Labrador must vie with many world-class destinations. The province's remote location also makes travel distance, time, and cost a significant barrier. Finally, a short peak season limits the industry's profitability, as does the number and quality of accommodations, roads, and other facilities available to visitors.