Social and Economic Impacts

The growth of land-based industries during the first half of the 20th century helped diversify Newfoundland and Labrador's economy into sectors other than the fishery. As new mines and mills opened, the country began exporting larger quantities of mineral and forest products. Soon, the country expanded from a single-product export economy to one based on three – fish, minerals, and forest products.

A larger variety of jobs also became available to local residents with the advent of new land-based industries. Mines and mills attracted thousands of workers from across the country and paid them with cash, not credit. However, many families who moved to industrial towns had to adjust to a new way of life. Companies often owned all of the homes in the community and decided who could move in and where they would live. As a result, an atmosphere of oppression permeated many company-owned towns.

Diversified Economy

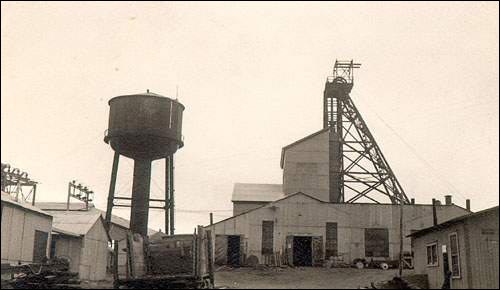

The early 1900s was a time of great economic change for Newfoundland and Labrador. As the railway allowed greater access to the island's interior during the 1890s, developers began to exploit the region's forest and mineral resources. Mines and paper mills began to appear in central and western Newfoundland and quickly assumed an important role in the country's economy.

Soon, the new land-based industries joined the fishery as Newfoundland and Labrador's major exporters. In 1929-30, forest and mining products accounted for approximately 55 per cent of exports, while fish accounted for about 43 per cent; in the five years preceding World War Two, forest products jumped to 48 per cent of total exports, while the fishery and mining industry each accounted for about 25 per cent. For the first time in centuries, Newfoundland and Labrador's economy did not entirely depend on the fishery.

Although the new industries helped diversify the country's economy, many of the new mines and mills belonged to foreign developers. Montreal businessman Robert Gillespie Reid, for example, owned the Reid Newfoundland Company, which built much of the railway as well as a prosperous newsprint mill at Corner Brook (it later sold the mill to the New York-based International Power and Paper Company); two Nova Scotian companies - the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company and the Dominion Steel Corporation - owned the Bell Island iron ore mines for much of their existence; and a pair of brothers from the United Kingdom, Alfred and Harold Harmsworth, owned the Anglo-Newfoundland Development (AND) Company, which helped establish a number of mining and forestry operations on the island, including the Buchans mine and Grand Falls pulp and paper mill.

Although the government yielded control over much of its new resources to foreign developers, it had also created thousands of new jobs for local workers outside the struggling fishery. By the late 1800s, both the cod and seal fisheries had fallen into decline because of poor prices and decades of over-exploitation. Few jobs, however, existed outside the fishery and many people had to leave the country to find work elsewhere.

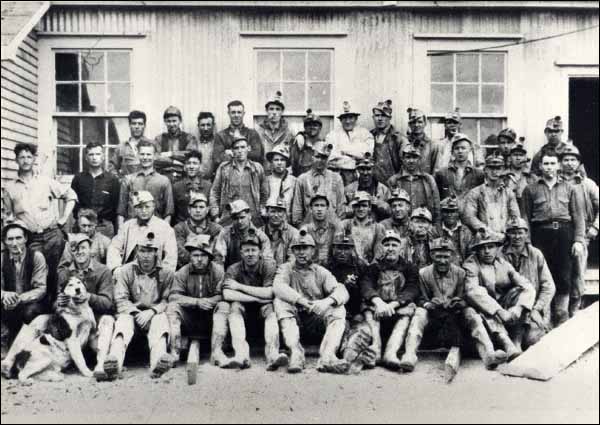

Recognizing that the traditional economy could no longer support a growing population, the government looked towards the development of land-based resources to provide additional employment. Although the fishery remained Newfoundland and Labrador's primary employer, the mining and forestry industries grew in importance. Thomas Liddell reported in his 1939 Industrial Survey of Newfoundland that approximately 14,000 people worked as loggers and 8,991 worked for pulp and paper mills. These figures represented both seasonal and full-time employees. The 1935 Census also reported that 1,800 people worked in the mining industry.

Company Towns

While the fishery was domestically owned and gave rise to a string of small settlements scattered along the coastline, workers for the forest and mining industries often had to live in large industrial centres. Many of these, like Grand Falls, Corner Brook, Buchans, and Wabana, were company-owned towns, which meant the workers' employer was also their landlord. As a result, mining and paper companies often exerted significant control over their workers' lives.

At Buchans, for example, the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) owned all of the town's houses and buildings, including its hospital and school. Workers were not allowed to build their own homes and instead had to live in company-owned bunkhouses, if they were single, or in cottages, if they were married. Although rent was cheap, these dwellings were often cramped and poorly maintained.

When the Department of Agriculture and Mines sent a committee to Buchans in 1929 to investigate living and working conditions, officials were shocked to learn that each bunkhouse bed accommodated two workers. The company did not provide mattresses for the men, who instead had to share double box springs. While the cottages provided better living conditions, there were rarely enough of them to accommodate each married couple. This made it impossible for many newlyweds to live together at Buchans.

ASARCO also owned the 37-kilometre railroad track to Millertown, which was the only way in or out of town until the 1950s. Company officials, therefore, controlled not only where their employees lived, but who could enter the town and who could leave. When a road to Badger was completed in 1956, many employees left the town and built their own homes across the river on land the company did not own.

The paper towns of Grand Falls and Corner Brook were also company owned. The AND Company was Grand Falls’ major employer and dominated almost every aspect of daily life. Only individuals who worked for the paper mill or had permission from the company could move to Grand Falls. Once there, residents had to rent homes from the company. In 1948, the AND Company relinquished some of its control when it allowed tenants to buy their homes over a 10-year rental period. At Corner Brook, the International Power and Paper Company also rented homes to workers, but many people were able to build their own on nearby land outside company borders.

Despite an atmosphere of oppression, many company towns provided workers with a much higher quality of life than fishing outports. Paper and mining companies built schools, hospitals, and roads, and supplied their towns with water, sewerage, telephones, and other services. Workers received cash wages instead of credit and often earned more than they would have in the fishery.

Although the mines and mills created steady employment with fixed wages, workers had to adjust to the rigid timetable of year-round industrial work. The company clock, and not the seasons, determined when employees would work. The new industries also provided few direct opportunities for women. Unlike the fishery, where women and children helped cure the fish, most jobs in land-based industries were exclusively for men. This helped create a divide between the home and work, where men were the primary and often sole breadwinners, while women were firmly planted in the domestic sphere. Nonetheless, the households of skilled workers and company managers employed domestic servants, usually hiring young women from fishing communities. Often recruited by kin and family friends who had managed to secure work in the company towns, such domestic servants supplemented the incomes of their fishing families back home.