Labour Organization and Unions

Until well into the 20th century, Newfoundland and Labrador's primary economic activity was in the fisheries. Most of the workforce was in the inshore cod fishery, a small-boat operation in which family enterprises caught, split, salted and dried the fish to produce a finished product that was traded to a merchant. Fishers were not wage workers but commodity producers, like farmers. Even in the Labrador and Grand Banks fisheries and the annual seal hunt, the workers were treated as independent contractors, paying for their own gear and supplies and receiving shares rather than wages.

Working in small, competitive units, scattered in isolated communities and at the mercy of merchants, fishery workers in the 19th century did not undertake much in the way of organized resistance against the difficult conditions of their lives. They did, however, from time to time engage in spontaneous acts of rebellion against local merchants or some other authority when they felt their rights were being violated. Several examples are documented from the Harbour Grace/Carbonear area in the early 19th century.

The seal fishery was unusual in that it brought together large groups of workers who laboured under similar conditions for similar rewards, remained together for extended periods, and in many cases came together annually. It is not surprising, therefore, that the first recorded organized, mass strikes were staged by sealers. In the 1830s and 40s, there were strikes, marches, and other demonstrations by thousands of sealers in St. John's, Conception Bay, and elsewhere, protesting the harsh and dangerous conditions in which they worked, and the poor reward they earned.

Unions in the Early 19th Century

It is also not surprising that the first formal workers' organizations in Newfoundland and Labrador were generated among tradesmen in maritime occupations, such as shipwrights, followed by other trades such as coopers and masons, mostly in St. John's. They were modelled after British trades organizations: most were called “protective associations” and incorporated some of the functions of fraternal societies, such as sickness benefits and burial insurance. Other city workers also formed organizations, such as the retail clerks' union formed in 1868, the first Newfoundland and Labrador union to have women as members.

In the late 19th century, the government began to promote industrial diversification based mainly on land resources. A trans-island railway was built, and mines and paper mills created enclaves of industrialization. The new industries were undertaken by large international corporations, and some of them generated local branches of international unions. Newfoundland and Labrador-based unions such as the Longshoremen's Protective Union (L.S.P.U), the Newfoundland Industrial Workers' Association, and the Wabana Workmen and Labourers' Union fought lengthy struggles for recognition, wages and conditions.

Smallwood's Influence on Unions in Newfoundland and Labrador

In 1908 William (later Sir William) Coaker founded the Fishermen's Protective Union (FPU), the first organized protest movement among fishing people in Newfoundland and Labrador. Acting in part as a cooperative, the FPU attempted to break the grip of the merchants on the cod fishery. Coaker was elected to the House of Assembly along with several other FPU members, but by the 1920s he had lost his reformer's zeal, and the organization became not much more than a group of companies, trading in a manner similar to the traditional merchants.

The young Joseph Smallwood was an admirer of Coaker, and in the 1920s he learned a good deal about labour organization while working in the United States as a reporter for socialist newspapers and an organizer for leftist parties. He came back to Newfoundland and Labrador as an organizer for the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers, founded a Federation of Labour, and walked the railway tracks organizing track labourers.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s union membership declined, although there were some very active areas, such as among the woods workers. In 1937, a group of activists formed a Trade and Labour Council (later the Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour) and embarked on an organizing campaign which continued during the years of the Second World War. With the War and the building of American bases both wages and prices rose, and with them union militancy. In 1941, for example, there were ten major strikes, involving more than 4,000 workers.

By the end of the War, the proportion of organized workers in Newfoundland and Labrador was higher than in Canada. In 1946, when a National Convention was elected to decide Newfoundland and Labrador's constitutional future, many union leaders ran, and of the 45 members elected, six had union affiliations. In 1949, Newfoundland and Labrador became Canada's tenth province and Joseph Smallwood became its Premier. His government quickly passed a series of laws that gave the new province some of the most progressive labour legislation in the country.

At the time, it was the policy of the Canadian Labour Congress to merge small local unions into the large, U.S.-based internationals. In the Newfoundland and Labrador logging industry, which supplied the two large paper mills, about 12,000 loggers worked under appalling conditions for low wages. They were represented by three rather weak independent unions. With the backing of the Canadian Labour Congress, the International Woodworkers of America began a tough, efficient organizing campaign. It was a new style of labour struggle for Newfoundland and Labrador, and when a police officer died after a confrontation, Smallwood's government decertified the IWA and went on to pass a series of harsh restrictions on union activity. It was not until Smallwood's government was replaced in 1972 that relations between government and unions returned to normal.

Unions in the Late 20th Century

Although a considerable amount of salt fish was still being produced, by 1970 a major part of the fishing industry was devoted to freezing operations, industrial enterprises with employees paid by the hour. The 5,000 fish plant workers were eligible for union organization, but the 18,000 or so inshore fishermen were still regarded as independent producers rather than as employees, and were therefore not covered by collective bargaining legislation. About 1,000 crewmen on the trawlers (or draggers) that fished the offshore banks were also excluded, being regarded as “co-venturers” with the companies that owned the ships.

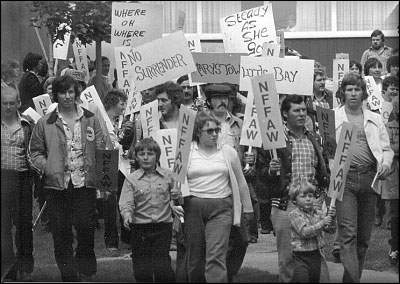

During the 1970s, an organization that began among inshore fishermen on the West Coast of the island, led by a St. John's lawyer and a Corner Brook priest, brought the three groups of fishery workers together into one organization, the Newfoundland Fishermen, Food and Allied Workers Union (later called the Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union), as an affiliate of a large American-based “international” union. In a series of tough and bitter strikes, the union won collective bargaining rights and better prices for fishermen, and major wage increases for plant workers. In the 1980s, the union terminated its international affiliation and became an affiliate of the Canadian Auto Workers.

Since the late 19th century Newfoundlanders and Labradorians have gone abroad to work, and among them have been many who have made a contribution to labour organization in their new homes. The International Association of Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Ironworkers, for example, has numbered many Newfoundlanders and Labradorians among its officers. Among the best-known expatriate Newfoundlanders and Labradorians in Canada are the late Senator Eugene Forsey, who worked for the Canadian Labour Congress in the 1930s and 40s, and Ed Finn, who also worked for the Canadian Labour Congress, wrote a column for the Toronto Star, and has worked for the Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers, the Canadian Union of Public Employees, and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

In the 1990s, although unemployment was high and per capita incomes low, the percentage of Newfoundland and Labrador workers who were union members was still the highest in Canada. Some of the largest and most influential unions were in the public service, such as the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) and the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Public Employees (NAPE). The latter union, particularly, also had a number of locals that were not in government jobs. Unions of health workers and teachers were also powerful and influential.