Lifestyle of Fishers, 1600-1900

European fishers had been working off Newfoundland and Labrador's coasts for about 100 years by the turn of the 17th century. Most arrived by May or June to exploit abundant cod stocks before returning overseas in the late summer or early fall. Known as the transatlantic migratory fishery, the enterprise prospered until the early 19th century when it gave way to a resident industry.

As the number of permanent settlers at Newfoundland and Labrador increased throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the lifestyles of workers engaged in the fishery changed. The household became an important part of the industry because resident fishers were increasingly able to rely on relatives for assistance instead of on hired hands. At the same time, the emergence of the seal hunt and other winter industries allowed fishers to diversify into other sectors and work year-round. A growing resident population also led to dramatic social and political changes, giving fishers and their families access to schools, churches, hospitals, poor relief, and many other services and institutions.

Despite these developments, many similarities remained between fishers in the 19th century and their 17th-century counterparts. Handlines, small open boats, and other gear remained largely unchanged since the days of the migratory fishery, as did the basic techniques of salting and drying fish. Inshore fishers of both the 17th and 19th centuries lived in coastal areas that were close to cod stocks, and they rowed to fishing grounds each morning before returning home in the evening or night.

Migratory Fishery

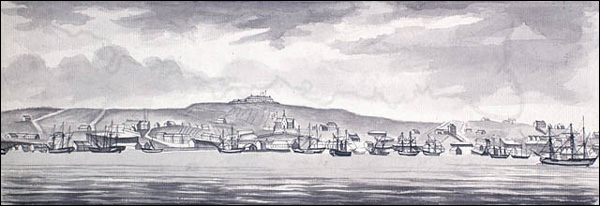

The migratory fishery was a seasonal industry that required most of its workers to live in Newfoundland and Labrador on a temporary basis only, usually during the spring and summer when cod were plentiful in offshore waters. France, Spain, and Portugal participated in the early migratory fishery, but it was England that eventually dominated the industry, each year dispatching shiploads of fishers from its West Country ports.

Despite the dangers and expenses associated with annually sending thousands of men across the Atlantic, British fish merchants and government officials did not initially want to establish year-round settlements at Newfoundland and Labrador. The region had limited agricultural potential and offered few opportunities for winter work, which meant the state would likely have to spend large sums of money supporting colonists. Fish merchants also feared a resident industry would interfere with their profits from the lucrative cod trade.

As a result, most fishers working at Newfoundland and Labrador in the 17th and 18th centuries were not permanent residents. They instead travelled across the Atlantic each year in large ocean-going vessels and spent only a few months overseas before returning west in the late summer or early fall. During this time, the vast majority of fishing people were separated from their families and their homes. Most were in the employ of West Country merchants, who traded goods and credit to fishers in return for cod; the merchants then sold the fish to domestic and foreign buyers.

Lifestyle of Migratory Fishers

While at Newfoundland and Labrador, the lifestyles of migratory fishers revolved around their occupation; workers spent most of their waking hours catching and curing fish, which left them with little leisure time. Immediately after arriving in the spring or early summer, workers had to first spend much time and energy cutting timber and building the infrastructure of the fishery: stages, which fishers used to tie up their boats and unload their catch; flakes, where fishers laid out their cod to dry; and cabins, cookrooms, and other structures where workers slept, ate, and retreated for shelter. Workers built camps in coastal areas that would ensure easy access to productive fishing grounds.

After the construction phase was completed, fishers spent the remainder of their time at Newfoundland and Labrador catching cod and processing it for sale. Workers rowed to fishing grounds in small open boats early each morning and returned to shore when their vessels were filled with cod. The men fished with long handlines – sometimes up to 55 metres long – that had a hook attached to one end. Fishers baited the hook with squid or capelin, dropped it in the water, and repeatedly pulled the line up and down to attract cod, often having to re-bait the hook.

Once fishers unloaded their catch onto the stage, members of the shore crew processed it. Headers removed the cod's head and guts; splitters cut out the backbone, and salters covered the fish with salt for curing. Next, workers spread the fish out on flakes or beaches to dry in the sun and air. The drying process could take weeks and workers had to regularly turn the fish to ensure even drying; they also had to cover the product or bring it inside whenever it rained. The shore crew's work was of vital importance, as the quality of cure often determined how much money cod would fetch at the market.

Labourers in the migratory fishery worked long hours – often from daybreak until dusk. Whatever leisure time they had was likely spent with colleagues, as most men were separated from their families and lived in makeshift cabins. Storytelling and music may have been popular pastimes that would have allowed many people in the group to take part. Fishers also met at the local smithy each evening to drink, smoke, and socialize. Blacksmiths existed in many harbours during the 17th century to repair and manufacture boat fixings and other metal items. Their workplaces, known as smithies or forges, were much warmer than most other local structures and often doubled as taverns in the evenings. Archaeologists at Ferryland have uncovered a wide range of clay pipes and ceramic drinking vessels in a local 17th-century smithy which indicate that structure also served as a cookroom and tavern.

Resident Fishery

The lifestyle of fishers remained largely unchanged until the migratory fishery gave way to a resident industry in the early 1800s. The number of permanent settlers at Newfoundland and Labrador gradually increased during the 17th and 18th centuries for a variety of reasons. Planters and merchants hired caretakers to overwinter on the island and guard fishing gear; wars sometimes made it difficult for people to cross the Atlantic and return home; and the emergence of proprietary colonies in the 1600s helped create a foundation for permanent settlement. The Irish and English women who began to come to Newfoundland and Labrador in greater numbers during the 1700s, often to work as servants for resident planters, were crucial to settlement. Many married migratory fishers or male servants and settled on the island to raise families.

The Napoleonic and Anglo-American wars of the early 1800s also did much to turn Newfoundland and Labrador's inshore fishery into a resident industry. As the French and American fisheries declined between 1804 and 1815, Newfoundland and Labrador cod became more valuable on the international market. This prompted many English and Irish fishers to permanently settle on the island instead of traveling there each summer to fish.

Instead of the large-scale fishing operations of the migratory fishery, which were directed by merchants and involved sizeable boat and shore crews, smaller household operations, largely relying on family labour, underpinned the resident fishery. Women and children assumed much of the work formerly done by headers, splitters, and salters, while men and older boys harvested cod. Fishers continued to use handlines throughout the 1800s, although some used more efficient gear, including cod seines, trawl lines, gillnets, and cod traps.

Otherwise, the nature of the inshore fishery remained largely unchanged. Fishers left their coastal homes early each morning to row or sail to nearby fishing grounds and returned when their boats were filled with cod. The shore crew split, salted, and dried the fish. One day each week was also devoted to catching bait – usually squid and capelin. As in the migratory fishery, fishing people traded their catch to merchants for food and supplies, or for credit in the merchant's stores. Instead of dealing with West Country firms, many 19th-century fishers worked for merchants based in Newfoundland and Labrador.

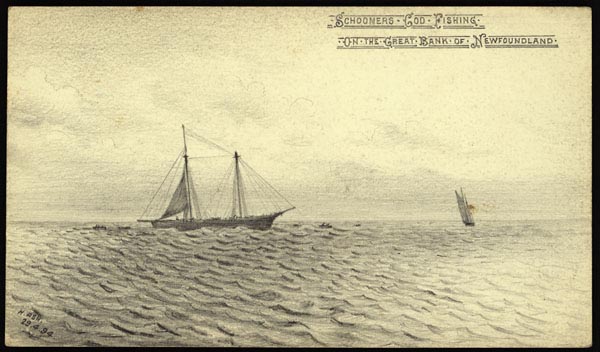

Some resident fishers also participated in the Labrador and bank fisheries. The former grew in popularity when some of the island's inshore cod stocks showed signs of depletion after 1815, prompting fishers to migrate to Labrador each summer and fish there. The Labrador fishery consisted of two groups: stationers and floaters. Islanders who set up living quarters on shore and fished each day in small boats were known as stationers, while floaters lived on board their vessels and sailed up and down the Labrador coast, often journeying further north than stationers.

Permanent residents also engaged in the offshore banks fishery by the 1860s, in part to compensate for declining inshore stocks. This industry typically ran from March until October, although the fishing season could vary from one community to another. Wooden schooners, sealing steamers, and other ocean-going vessels made three or four trips to the banks each season and often remained there for weeks before returning home. Women and children did not participate in this industry, as fishers often cured their catch at sea.

Other Activities

To support themselves and their families throughout the year, many resident fishing people engaged in a wide range of economic activities during the 19th century. These included hunting game and trapping furs in the fall and winter; woodcutting in the winter; sealing in the winter and spring; and fishing, farming, and berry picking in the spring, summer, and early fall. Many families spent the warmer months near the shore to harvest fish and other coastal resources, before moving further inland during the fall and winter to cut timber and hunt game. Private vegetable gardens were also common in many rural communities. Most households grew crops that were easy to care for, preserved well, and were compatible with Newfoundland and Labrador's poor soil and cold climate. Cabbages were popular, alongside a variety of root vegetables, including potatoes, turnip, carrots, parsnip, beets, and onions.

Better-developed social and political services also emerged during the 1800s to support a growing resident population. By the end of the century, many fishing people and their families had access to schools, doctors, nurses, churches and other services. The colony acquired much greater political autonomy, with the inauguration of Representative Government in 1832 and Responsible Government in 1855, and supported its own print media after 1807. Better modes of communication and transportation – including steamers, the railway, and the telegraph – also connected the Newfoundland and Labrador people to each other and the rest of the world on an unprecedented scale.