Environment, Climate, and the 19th-Century Economy

Newfoundland and Labrador's physical environment greatly influenced the ways settlers made a living during the 19th century. The richness of marine resources encouraged a pattern of coastal settlement and made the cod and seal fisheries central to local economies. In contrast, the relative scarcity of good soils and other terrestrial resources made large-scale farming operations impractical and discouraged year-round habitation of interior spaces.

The climate and weather also shaped economic and subsistence activities. Long cold winters, strong winds, and a generally harsh climate prompted many settlers to leave their coastal homes during the colder months and move to more sheltered areas inland. Instead of fishing, residents spent much of their time and energy harvesting firewood and hunting caribou and other game. The summers brought warmer temperatures and a moist climate that allowed people to harvest indigenous berries and cultivate small vegetable gardens. The short growing season and poor-quality soil, however, made it possible for families to cultivate only a limited variety of hardy vegetables.

Natural Environment

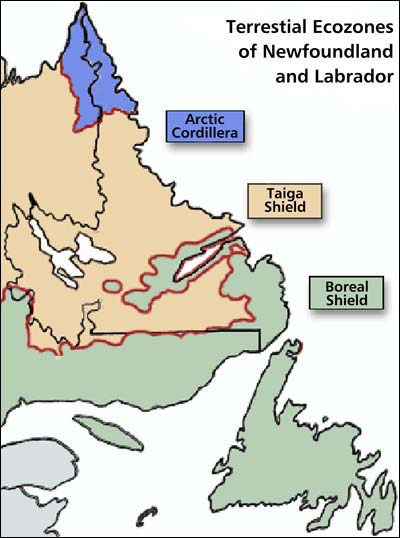

The natural environment encompasses all living and non-living features of a region – including flora, fauna, water, minerals, and climate – that occur naturally instead of being manufactured or introduced by humans. Newfoundland and Labrador's natural environment is characterized by three distinct ecozones: the Arctic Cordillera in northern Labrador, the Taiga Shield in central and southern Labrador, and the Boreal Shield on the island. Most human activity took place in the Taiga and Boreal Shields during the 1800s, although the Inuit made use of some areas in northern Labrador.

The Arctic Cordillera is an inhospitable mountain range characterized by long, dry, and extremely cold winters. The Taiga and Boreal Shields are more hospitable areas with slightly warmer temperatures and greater amounts of precipitation; however, these regions also display harsh climates, long cold winters, and short humid summers. The landscape is rocky in many areas, especially near the coast, with many wetlands and coniferous forests. Soils are often acidic and not very rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients important for crop growth.

Newfoundland and Labrador was home to a variety of land and marine mammals during the 19th century, including bear, lynx, wolves, marten, weasels, fox, caribou, beaver, arctic hare, seals, and whales. Cod, herring, salmon, trout, capelin, and a variety of other fish species frequented interior and coastal waters, while ducks, geese, ptarmigan and other game birds were also abundant. The colony also supported a wide range of edible berries and herbs, including blueberries, strawberries, bakeapples, raspberries, partridgeberries, dandelions, and Labrador tea.

People and the Environment

Newfoundland and Labrador's economy was closely tied to its natural resources during the 19th century. People made a living by catching fish and marine mammals, cutting wood for fuel and building materials, hunting caribou, hare, and other game, growing vegetables, and gathering wild herbs and berries. Because most resources were only available for limited times of the year and only in certain areas, most settlers had to budget their time and labour around when and where resources would be available; to do this, many rural residents adopted a system of seasonal mobility that allowed them to exploit different resources as they became available or most needed.

Mild weather during the spring, summer, and early fall allowed residents to live in exposed coastal areas and exploit nearby resources. This was facilitated by the lifecycles of many fish and plant species, which matured during the warmer months. Both cod and lobster, for example, were available from spring until fall, while capelin arrived at coastal areas in June and July. A variety of berries also ripened in the summer and fall – strawberries in late June and early July, raspberries in July, bakeapples in late July and early August, blueberries in August, and partridgeberries in September. In addition, the warmer months allowed residents to cultivate vegetable gardens at their coastal homes. Most families grew potatoes, cabbages, carrots, turnip, parsnip, onions, beets, and other vegetables that preserved well and were resilient enough to grow in colder climates, poor soil, and relatively small plots.

The fall and winter brought fewer resources and harsher climates to exposed coastal areas. The growing and fishing seasons had both ended, while strong winds, snowstorms, and cold temperatures made it difficult for residents to heat their homes. To compensate, many families moved inland or to sheltered bays during the colder months to take advantage of milder weather and more varied resources. Most settled in or near forested areas where they could harvest plenty of firewood and lumber for building and repairing boats, homes, furniture, and other structures. Various big and small game species were available inland during the winter months, including caribou and arctic hare; some settlers also trapped furs for private use and sale to commercial businesses.

Residents in southern Labrador and northeastern Newfoundland were able to hunt seals in the winter and early spring, when Arctic ice filled coastal waters. As harp seals migrated south for a one- or two-week period in December and early January and then north again in February and March, local residents trapped them with nets attached to the shore; this was a lucrative activity that became known as the landsmen seal fishery.

Many people in Newfoundland and Labrador also participated in the annual spring seal hunt during the 19th century. Each year, sealing fleets travelled to the Gulf of St. Lawrence or the ice floes off Newfoundland's northeast coast to harvest seals. The hunt usually began in early March, before seal pups were old enough to leave the ice, and ended in late April or early May when it was time to prepare for the cod fishery and begin another cycle of economic and subsistence activities.

Although the annual cycle of seasonal activities could under ideal conditions perfectly complement each other and sustain Newfoundland and Labrador households throughout the year, this was not always the case. Some families did not find it practical or desirable to engage in all seasonal activities or to migrate from coastal areas to interior ones during the fall and winter. Fishers were less likely to move inland when the fishery was profitable because they had more credit to spend at merchant's stores than they did when the fishery failed. Residents of St. John's and other large centres rarely migrated inland and were less likely than their rural counterparts to keep vegetable gardens or hunt game, largely because they owned less land and had access to shops and other conveniences.