John Thomas Mullock's Bibles

The academic study of the Bible began in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries and was conducted by Catholic humanists such as Desiderius Erasmus who wanted to establish a more reliable critical edition of the text. After the Reformation in the sixteenth century, however, the study of Hebrew and Greek became a particular concern for Protestants who, responding to the Reformers’ rallying cry of sola scriptura (salvation by Scripture alone), wanted to read the biblical texts in their original languages. Since the Council of Trent (1545–63) restricted all unauthorized translations of the Bible, Catholics were often slower to respond to the advances make in Hebraic and Greek study over the next two centuries. It is significant, however, that Bishop Mullock took the academic study of the Bible very seriously.

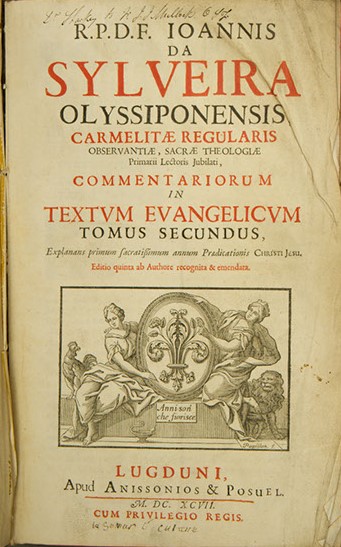

The Mullock collection contains a number of Bibles as well as some rather sophisticated Bible study tools. While there are no Hebrew Bibles extant in the Mullock collection, it is very likely that he possessed a number of these as there are several Hebrew reference books in the collection. There are four Greek New Testaments, and an Italian one that Mullock no doubt acquired when he was in Rome (1829–30) as it is signed “Fr Giovanni T. Mullock.” One of the Greek New Testaments is a very small late-sixteenth-century edition which could easily be carried (or hidden) in a waistcoat pocket and probably used for devotional purposes. His library also has an excellent copy of the Vulgate printed in 1630, which he probably purchased on his travels in Europe. The Vulgate is Jerome’s famous translation produced between 385 and 405 and was the official Bible of the Catholic church.

One Bible, however, stands out among the rest, not for its antiquarian interest but for its translation: an 1828 version of the King James Bible, the official Bible for the Church of England. Mullock’s inscription on the title page reads: “ad usum P. Joannis T. Mullock OSF cum licentia Pii VIII P.M.” (for the use of Father John T. Mullock with the permission of Pius VIII, P[ontifex] M[aximus]). This would also date the acquisition of the Bible between March 31, 1829, and November 30, 1830, the dates of Pius VIII’s papacy, when Mullock was studying in Rome. The inscription is all the more extraordinary considering Pius VIII’s views on translations of the Bible that were not officially sanctioned by the church. In his papal encyclical Traditi humiliti, issued on May 24, 1829, Pius VIII warned: “We must also be wary of those who publish the Bible with new interpretations contrary to the Church’s laws. They skillfully distort the meaning by their own interpretation. They print the Bibles in the vernacular and, absorbing an incredible expense, offer them free even to the uneducated. Furthermore, the Bibles are rarely without perverse little inserts to insure that the reader imbibes their lethal poison instead of the saving water of salvation.”

But what are the differences between Catholic and Protestant Bibles? While both have the same number of books in the New Testament (27), the Vulgate contains 46 Old Testament books whereas the King James Version contains 39. The seven books left out of the Protestant Bible (Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, and I and II Maccabees) are sometimes included in a section called the “Apocrypha” (a Greek word meaning “hidden”). In the Vulgate, there are also some additions to Daniel and Esther that can actually change the interpretation of these books. The differences between the Bibles are probably due to the fact that Jerome translated his Old Testament using the canon of the Greek-speaking Jewish community at Alexandria, whereas the Protestants (largely under the influence of Luther) based their translations on the canon of the Aramaic-speaking Jews in Palestine. The Palestinian/Protestant canon is the same as the Jewish one, except for the order and the arrangement of the biblical books.