A Complete Course in Theology: Jacques-Paul Migne

Jacques-Paul Migne was born in Saint-Flour, Cantal (about 400 kilometres south of Paris), and studied for the priesthood in Orléans. In 1833 he came to Paris, with the permission of the bishop of Orléans (Jean Brumeaux de Beauregard), after he had refused to bless the procession held on the Feast of Corpus Christi in 1831 because the revolutionary tricolours were on display in the procession. In Paris he quickly became involved in newspaper publishing, founding L’Univers religieux in 1833, a periodical with strong ultramontane (a movement that placed a strong emphasis on the power of the papacy) leanings. In 1836 he founded a publishing house, the Imprimerie Catholique (later known as the Atelier Catholique), in Petit-Montrouge, in the southern suburbs of Paris. There he began to publish volumes in a grandiose publication plan of what he called the Bibliothèque universelle de clergé, consisting of a number of series of multi-volume works which he sold largely to bishops and priests. Most of these series continue to be of interest to historians of nineteenth-century religion and politics in France. Two of them continue to be the primary source of texts of the medieval Greek and Latin patristic and ecclesiastical writers. Between 1836 and 1868 Migne published nearly 1,000 volumes in total. These series include the following, which are still preserved in the Basilica Museum as part of the Mullock collection, with the exception of the Patrologia Latina, the Patrologia Graeca, and the Theologiae series, which were transferred to Memorial University’s Queen Elizabeth II Library in 1965:

- Encyclopédie théologique, Première Série (52 volumes, 1844–45)

- Encyclopédie théologique, Deuxième Série (53 volumes, 1845)

- Encyclopédie théologique, Troisième Série (66 volumes, 1845–46)

- Nouvelle encyclopédie théologique (52 volumes, 1851–55)

- Collection intégrale et universelle des Orateurs Sacrés (99 volumes, 1844–66)

- Scripturae sacrae cursus completus (28 volumes, 1839–43)

- Theologiae cursus completus (28 volumes, 1839–45)

- Démonstrations evangéliques (20 volumes, 1843–53)

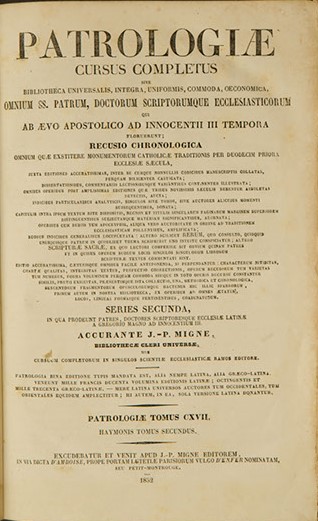

- Patrologiae cursus completus, series Latina (221 volumes, 1844–55)

- Patrologiae cursus completus, series Graeco-Latina (166 volumes, 1857–66)

- Patrologiae cursus completus, series Graeca (104 volumes in 85 parts, 1856–67)

Migne believed fully in the power of the printing press, and until a fire destroyed his printing factory in 1868, his publishing house was the largest privately owned publisher in France, using steam-driven presses (then the latest technology in printing) and employing hundreds of workers. He sold the books on subscription, offering discounts on prepaid subscriptions and further discounts if someone contracted to purchase additional copies of the series he made available. The patrology series (Patrologia Latina in Latin, Patrologia Graeca in Greek, and Patrologia Graeco-Latina in Greek with facing-page translations into Latin) was originally devised by Dom Jean-Baptiste Pitra (1812–89). However, Pitra’s contribution is almost exclusively anonymous, except for a single entry in one of the index volumes of the Latin series (PL 218, col. 338). Pitra edited the first two volumes of the Latin series (the works of Tertullian), provided notes for some of the others, and searched indefatigably for manuscripts of patristic texts; but the majority of the texts were taken from seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century editions, many of them provided by Dom Prosper Guéranger, abbot of the Benedictine abbey Solesmes. Migne rarely if ever paid royalties, as a result of which he was frequently in trouble with the authorities for plagiarism of editions still under copyright.

Although most of the series he published have long since been superseded (at least as reliable sources of information), the Latin and Greek collections of the church fathers are often still the primary or only editions available in accessible editions, despite the fact that these editions have often been criticized for being hastily put together, printed on cheap paper, and sometimes published without permission. But despite these criticisms, both the Greek and Latin series continue to be useful to scholars, and because of Migne’s policy of suppressing nearly all references to his many collaborators, both series continue to be known collectively as “Migne.” They have been described as the collection of editions that made medieval studies possible. To someone like Mullock, this kind of reference work would have represented a treasure trove of such texts and formed a cornerstone of the library he envisioned. It must have been especially useful for the seminarians of St. Bonaventure’s College. Modern students of the Middle Ages often depend on translations, but serious scholars of the period still consult these series regularly.

Mullock owned the entire set of the Latin series (the title page of each volume carries his signature or one of his Episcopal stamps), bound in uniform dark blue bindings (as supplied by Migne), and the first 105 volumes of the Greco-Latin series, representing the first series of Greek fathers (from St. Barnabas [died 61CE.] to Photios [810–91]); some of these volumes additionally have notes in his handwriting.