Niccolò Machiavelli and His Critics

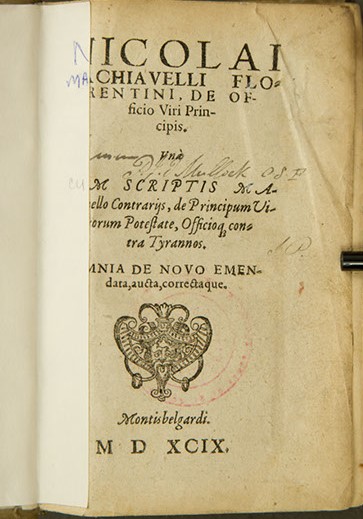

The Florentine statesman and scholar Niccolò Machiavelli’s Il principe (The prince) was originally published in Italian in 1513 while the writer was in exile in Saint Andrea, Italy. The Latin version, De officio viri principis, in the Mullock collection appeared in 1599 and is bound together with the Huguenot Stephanus Junius’s political tract on tyranny, Vindiciae contra tyrannos (1580). Mullock also had copies of Machiavelli’s complete works published in Italian. Since its publication, the reading public has been both fascinated and horrified by Machiavelli’s The Prince. Some praise it, arguing that its realist approach to politics was well ahead of its time. Others condemn it as a justification for the politically powerful to prey on the weak or as a rationalization for immoral and unchristian comportment. Given the latter view, it is not surprising that The Prince spent time on the Index of Prohibited Books. Even today, as a result of its contents, Machiavelli’s name is synonymous with a cold-hearted realpolitik style of politics or behaviour where the means, no matter how cruel or inhuman, can be justified simply by citing certain ends. Indeed, to be accused of being “Machiavellian” is generally not a compliment.

By contrast, there is widespread agreement that the significance of The Prince has been immense. For scholars of the history of ideas, The Prince represents a fundamental leap in the evolution of Western political thought away from the medieval tradition (which was dominated by figures such as Thomas Aquinas) toward the familiar modern, contemporary world of political science. For scholars of politics and political practitioners, The Prince outlines a unique and fascinating theory of statecraft which turns on the effective accumulation and use of power (broadly understood as including manipulation, violence, and everything in between). For Machiavelli, the goal of successful statecraft should always be political stability and the continued survival of the state. Both principles have remained important to the study and practice of politics.

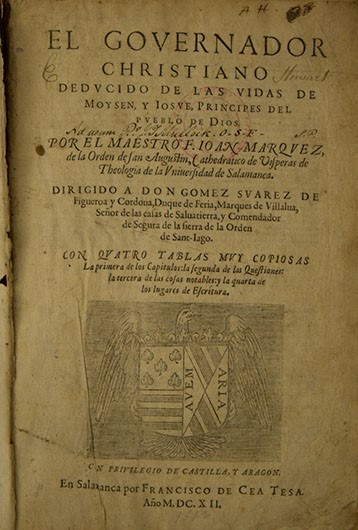

Mullock purchased his copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince after his 1830 ordination. In 1838 he also acquired one of many refutations of Machiavelli produced in Europe, El governador christiano (The Christian governor) (1612), by the Spanish theologian Juan Márquez (1565–1621), in 1612. This book is but one example of the many refutations of Machiavelli produced in Europe after the publication of The Prince. Just as Machiavelli had, Márquez intended his book to be a practical guide for rulers. However, unlike The Prince, which connects statecraft with the successful use of power, El governador christiano links statecraft to Christian ethics. Rather than condemning Machiavelli’s political theory, Márquez proposed that moral theology should address Machiavelli’s ideas, and he promoted the value of an alternative biblical reason of state.