John England and the Irish American Church

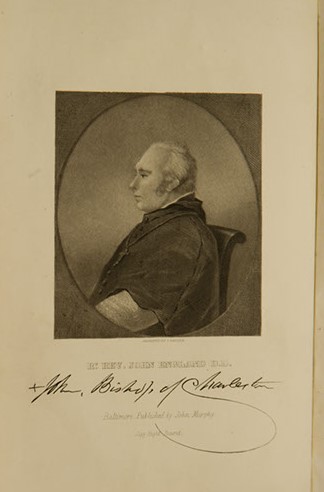

As attested by his extant book collection, Bishop Mullock closely followed the career of his fellow Irish bishops in the United States. He acquired the collected works of arguably one of the most radical and charismatic figures of early nineteenth-century American religious politics, John England (1786–1842), who, in many ways, served as a model for Mullock’s religious, social, and educational reforms. Similar to children from prosperous Irish families, England was first educated at Cork Protestant School and then at the Catholic St. Patrick’s College in Carlow. He was ordained at an early age, in 1808. He rapidly became involved in political controversy, as an ardent supporter of the nascent Catholic Emancipation in Ireland. His use of mass gatherings as a means of political agitation was later famously implemented by the Irish patriot Daniel O’Connell. To promote religious liberties and the separation of church and state, England founded the Cork Mercantile Chronicle, which he continued to edit until his elevation to the bishopric of Charleston in South Carolina in 1820, a sparsely populated and particularly challenging see. Although there was a sharp increase in the Catholic population due to large numbers of Irish and German immigrants in the 1830s, the Roman Catholic church was generally regarded as an absolutist and un-American institution in the period.

In 1826, England, the first Catholic priest to deliver a speech before the Congress of the United States, set out to challenge this widespread view and argued for the compatibility of republicanism and Catholicism. He advocated religious tolerance and the rights of other religious minorities (including Jews), and he opened a school for free black children, which he was later forced to close under pressure from municipal authorities. Although in his private letters he detested slavery, he maintained publicly a more ambivalent approach to abolition, excusing the practice of domestic slavery. He was greatly concerned with education and the formation of the laity, championing classical education, science, and literature. He attempted to found a book society in every congregation, an effort which was embraced, on his initiation, by the Third Provincial Council of Catholic bishops in Baltimore in 1837. He established a college and seminary in 1825 and from 1822 he edited the United States Catholic Miscellany, the first American Catholic newspaper. After England’s death, his successor, Dr. Ignatius Reynolds, collected his writings in the present five-volume set. Following an introductory sketch of the life of Bishop England, some 350 pages are devoted to a controversy with the Spanish theologian and Anglican convert J. Blanco White regarding the truth of the church. The remainder of the volume is devoted mainly to a lengthy defence of the doctrine of the Eucharist.

Mullock acquired volume 1 for his personal use after he became bishop of St. John’s. England might have been a highly relevant model for Mullock not only because of his controversial writings or his educational reforms but also because of the leading role he played in the hibernicization of the American Catholic church. As a result of England’s and his chief ally Francis Patrick Kenrick’s (archbishop of Baltimore) untiring efforts, the Irish began to dominate most Episcopal appointments in the United States after 1835. Mullock must have been interested in this process because he purchased two volumes by Kenrick: The Primacy of the Apostolic See Vindicated Mullock acquired as bishop of Thaumacene between 1847 and 1850, and The Validity of Anglican Ordinations in 1850. He also owned a copy of the records of the Baltimore provincial councils (convened on England’s and Kenrick’s instigation) from 1829 onwards (Concilia provincialia Baltimori habita), which he received from William Walsh, archbishop of Halifax. Interestingly, England’s and Kenrick’s most dedicated supporter in Rome was the rector of St. Isidore’s, Paul Cullen (later archbishop of Armagh, then Dublin, and Primate of Ireland). Like Mullock, they all shared the same Irish Roman orientation and the same vision perpetuated with local variations by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (or Propaganda Fide).