Hugo Grotius and the Beginning of International Law

If the political career of Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) had been a success then he might well have never written his masterpiece De Jure Belli Ac Pacis. A child prodigy, he had published his first book at age fourteen. Grotius was both a scholar and, also from a young age, the holder of key political offices in his home Province of Holland (a part of the United Provinces of the Netherlands). His political downfall came in 1619 when his faction was brought down in a coup. Sentenced to life imprisonment, Grotius escaped and fled to the France of Louis XIII. He spent much of the rest of his life in Paris, first as a pensioner of Louis, and then from 1635 as Swedish ambassador to France. It was during this latter part of his life that he wrote many of his most famous works, including De jure belli ac pacis.

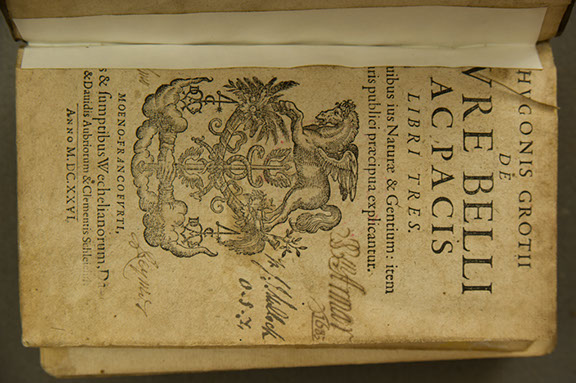

First published in Paris in 1625, De jure belli ac pacis was originally composed in Latin, and included in its earlier editions a dedication to Grotius’s patron Louis XIII. Grotius had started to write the book during his incarceration, but the bulk of the manuscript was written in France at the start of his exile between 1622 and 1624. The edition of 1626 in Mullock’s library was published in Frankfurt-am-Main and is largely a reprint of the original Paris printing of the previous year. This was, however, an unauthorized reprint of the original which was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1625. So, in modern parlance, this copy of De jure belli ac pacis in the Mullock collection is pirated.

In the work itself Grotius grapples with the contemporary seventeenth-century problems of finding a legal basis for the exercise and constraint of war. This is in a time when warfare had been seen to be increasingly destructive and often fought for capricious reasons. Using his knowledge of jurisprudence, theology, and ancient sources, Grotius sought to find a legal basis for both constraining and justifying war that was rooted in natural law. This approach, Grotius thought, would create a law of war that would be independent of local customary and religious differences. This tallied with his own theological concerns about the need to reunite a disunited Christendom. Despite the extent to which the text is a product of its epoch—dealing with contemporary problems using the scholastic and theological conventions of the time—it would come to be seen as one of the seminal works in the development of international law. The title of father of international law would also be bestowed on its author.

Grotius’s work has not been without its critics. Immanuel Kant, for example, included him in his list of “sorry comforters,” who in trying to mitigate the worst excesses of war still managed to justify the existence of violent conflict. Yet, for many mid-twentieth-century experts on international relations, Grotius’s legal approach offered a middle way between the excesses of a realpolitik based solely on power and radical attempts to overhaul the institutions of international affairs through international organizations. Grotius was seen as the champion of an approach to international order that, while recognizing the existence of conflicting sovereign states, placed this conflict within legal limits.

It is not clear why Bishop Mullock owned a copy of this book, which he seems to have acquired as a student. Grotius was an authority on Protestant theological questions, although De jure belli ac pacis is not considered to be a theological text, despite its references to sacred sources. Mullock’s interest in church history and Protestant “heresies” may be the link here. Eight of Grotius’s books (but not this one) had been banned by the Catholic church and were placed on the Index of Prohibited Books at different times. Furthermore, Grotius’s Arminianism is often regarded as an influence on the development of Methodism, a group that Mullock was particularly interested in. Grotius’s interest in the unity of Christendom, and his attempt to develop a jurisprudence independent of sectarian divides, might also have been a draw for Mullock.