Hebrew Research Tools

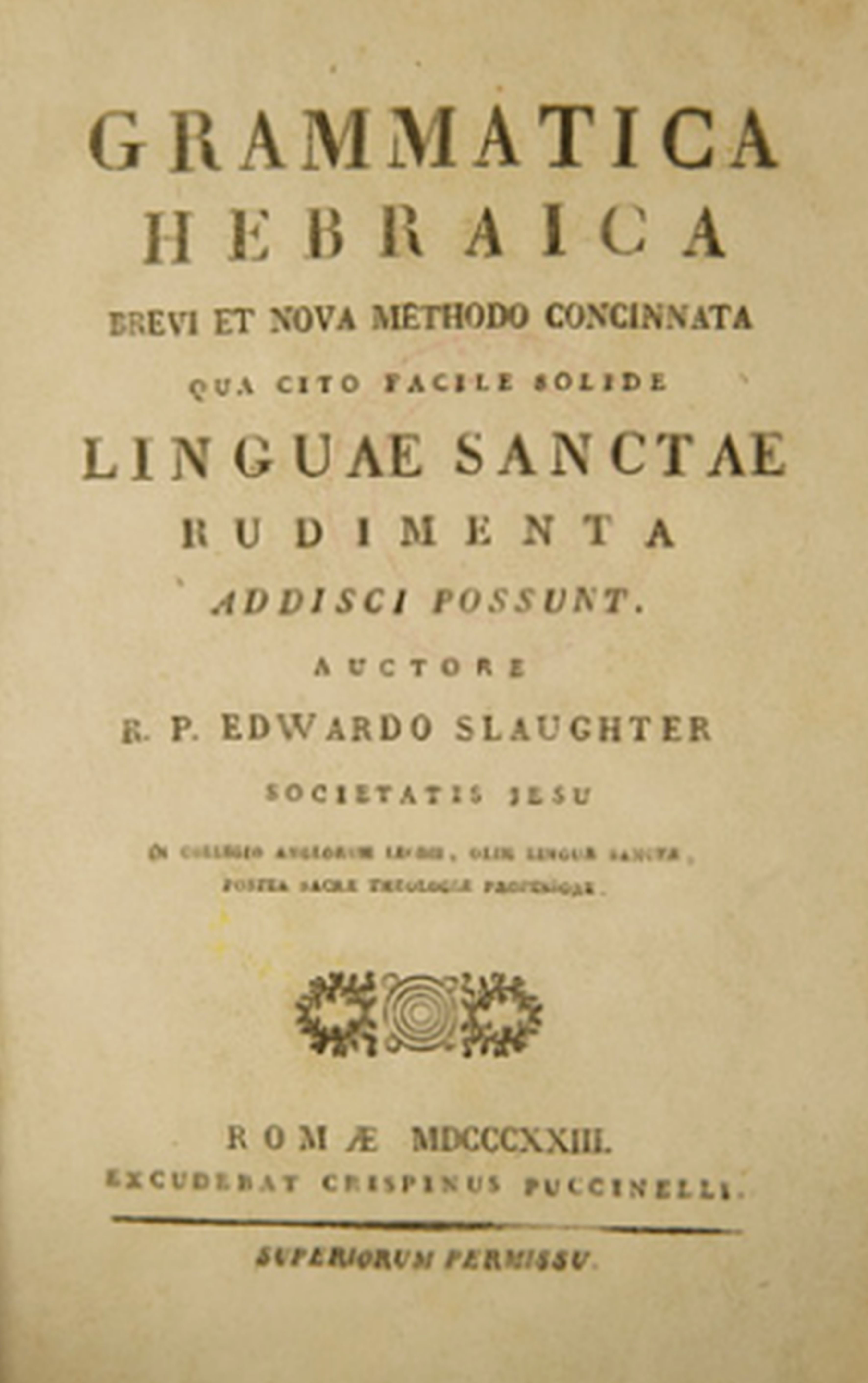

As well as having a large collection of Bibles, Bishop Mullock possessed a number of language tools that would have been of great assistance in his research. The Mullock collection contains four Hebrew lexicons and four Hebrew grammars, indicating his interest in reading and translating portions of the Old Testament. Judging from his inscription “Rome” in his copy of Edward Slaughter's Grammatica Hebraica (first published in Latin in 1699; Mullock had the 1823 edition), Mullock would have acquired this book as a 22-year-old student at St. Isidore's. Slaughter's grammar is a primer, suitable for someone who wants to learn the language very quickly. Interestingly enough, Mullock signs his name in Hebrew characters on the back page of the book as “m-u-l-l-l-o-ch.” The fact that he makes three spelling mistakes here (by the placing of a doubling daghesh in one of the lameds making three “l”s, ignoring the placement of the silent shewa under the first lamed, and not writing the correct final form of the letter kaph) indicates that he was just starting to learn the language. Nevertheless, he was interested enough in the language as a young student to make the attempt to sign his name in Hebrew.

Other language aids are also not without interest. Mullock acquired a first edition of François Masclef's Grammatica Hebraica (a Hebrew grammar liberated from the pointing invented by the Masoretes, 1716), while he was at Adam and Eve's in Dublin. Masclef (1663–1726) was a Catholic priest who devised a new method of studying Hebrew using an unpointed script (i.e., a script without the vowel markings), advancing the work of Louis Cappel (1585–1658). Cappel determined that the vowels in the Hebrew script were added by scribes called the Masoretes as late as 600 c.e., and were not original to the Hebrew language. This issue was quite controversial for the time and embroiled a number of scholars in the dispute, especially between Cappel and Johannes Buxtorf the elder (1564–1629) and Johannes Buxtorf the younger (1599–1664). Mullock also had a copy of John Parkhurst's A Hebrew and English Lexicon, without Points (1823) to which was affixed an unpointed Hebrew grammar. He also had a fourth grammar without points, published anonymously by James Duncan in London in 1828. The latter volume has Mullock's signature with the date of 1833, and contains a polemical preface concerning the pernicious effects of studying Hebrew using the vocalization developed by the Masoretes. It would seem, then, that Mullock not only studied Hebrew but he was also aware of philological disputes while he was a priest in Ireland only a few years after his first forays into Hebrew.

It appears, too, that Mullock pursued his language study and research while he was a bishop in Newfoundland. He had a copy of Paul Drach's edition of Wilhelm Gesenius's Hebrew and Chaldean lexicon, published by Jacques-Paul Migne in Paris in 1848. Since Mullock signs the book “Terre Nova,” he would have had it specially sent over to him sometime after he arrived in St. John's in 1848, which underlies his continuing interest in studying Hebrew.

This work in particular was at the cutting edge of Hebraic scholarship as it marks the first time that comparative Semitic philology was used to determine the meanings of words. Gesenius is known as the father of Hebrew lexicography, and English editions of Gesenius's lexicon such as Brown, Driver, and Briggs's Hebrew and English Lexicon (1906) remain a standard in the field. Interestingly enough, on the title page of Drach's edition Mullock writes the Hebrew word “h-l-k” (a word which means “to walk” or “to go”) without vowels. One wonders why Mullock would have chosen to write this in the book, especially as his annotations are so infrequent, but it does give evidence of a more sophisticated ability to write and read Hebrew. The fact that he wrote the word without vowels suggests what side of the theological fence he probably stood: he may have believed, like the anonymous writer of the 1828 grammar, that the Masoretes had corrupted the Bible by adding vowels to the consonantal text. In any event, it is certain that Mullock was interested in keeping up-to-date with the latest works in Hebrew philology while he was in St. John's.